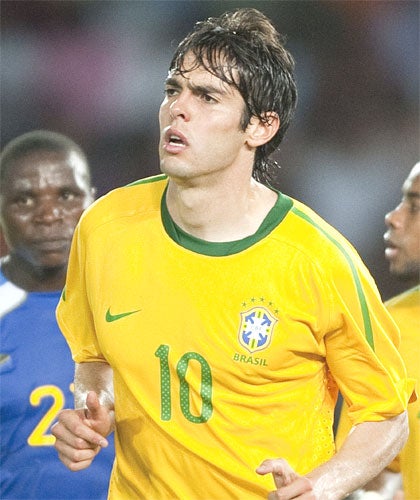

James Lawton: Kaka's challenge: to deliver on the promise that once wowed the world

The World Cup's Great Players: Kaka is far from the average Brazilian footballer. He never knew the squalor of the favela or had the fever to play the game as an escape

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are the players who threaten to ambush destiny in the next few weeks, who come to South Africa lacking only a fanfare of trumpets: Messi, Rooney, Torres, Drogba, Ronaldo and Ribéry. And then there is Kaka, the tall, withdrawn evangelist who has inscribed on the flaps of his boots: "I belong to Jesus" and "God is faithful".

But if Kaka still believes in God, does God still have faith in Kaka?

Real Madrid are believed not to do so and their new coach Jose Mourinho, in his trademarked, brutal fashion, is said to be keen to ship him out of town.

Has Kaka, who so recently was seen as a throwback to the best of Brazilian football, and by Manchester City as a whole franchise in himself, really become no more than a flawed adornment?

It is a complex, haunting story which we can begin conveniently enough at Berlin's Olympic Stadium.

Four years ago the man who would become the second most expensive player in football history, scored a goal that was so exquisitely executed that some were persuaded that in a few weeks time he would return to the formidable old stadium in Berlin not for a World Cup final but a coronation.

You could begin to warm up the anointing oils. Kaka ran with a wonderful fluency before sending a left-foot shot past the Croatian goalkeeper Stipe Pletikosa that spoke of all the reasons why the world contemplated his nation's football with such reverence.

The goal went beyond technical excellence. There was a familiar, surreal perfection that came from another planet.

So what happened to Kaka – and our understanding of how Brazil play the game?

For a while it seemed that he had been merely dragged down by a team utterly incapable of dealing with the burden of being world champions who were thought of, despite all the evidence of mediocrity in the 2002 tournament, as worthy heirs to the greatest tradition in the game.

Ronaldinho, we would know soon enough, had entered terminal decline as one of the great players. It was confirmed when he could scarcely raise a grimace as Zinedine Zidane's France swept Brazil off the road to Berlin in the quarter-finals. Ronaldinho was engulfed and Kaka was a casualty, replaced late in a game in which Brazil carried the whiff not just of losers but victims of a profound personality change.

They didn't play like Brazil and they didn't look like Brazil and it took a year of psychological rehabilitation, if not outright adoration, at San Siro to restore Kaka's self-belief. When Andrei Shevchenko left Milan, Kaka conquered San Siro brilliantly. He won the Champions League in 2007 and the Ballon D'Or by a mile from the young pretender Cristiano Ronaldo.

Yet now it is time for another coronation, not by ballot but in the action of the great tournament, Kaka is again in the margins.

Some regard him as the greatest of Real Madrid's galactico follies, £56m worth of false dawn, tetchy and bedevilled by injury that some at the Bernabeu are bitterly complaining was concealed by the minions of Silvio Berlusconi in Milan from medical documents.

In 22 appearances, and eight goals, for Real, Kaka, 28, has struggled desperately for the grace and the conviction with which he promised not only to revive Brazilian competitiveness in the World Cup but also restore some of their faith in the old virtues of the beautiful game.

Yet he insists that his faith in the way he can play, and how he can still illuminate the new, rugged Brazil made in the image of the combative coach and former World Cup winning midfielder, Dunga, is as strong and as fortifying as the one he has in God. "I have learnt in my life," he says, "that is it is faith which decides if something happens or not. I believe that Brazil can win the world Cup and that I can play a full part."

It is not the declaration of the average Brazilian footballer, but Kaka is far from that. He never knew the fetid squalor of the favela, he never had the fever to play football and escape, not like Pele or the "Little Bird" Garrincha or so many of the folk heroes who made Brazilian football. Indeed, he had a career option in tennis. His father was a civil engineer and his greatest crisis came not in a street fight but a swimming pool, where he fell and caused a fracture in his spinal column.

When the healing was clean and he was strong again at the broken place, he handed all credit to God and dedicated himself to a lifetime of evangelism.

Now he believes he will draw another dividend. He explains that you do not pray for specific rewards, but you set yourself ambitions, do your best and leave the rest to a somewhat higher adjudication.

En route to South Africa, where the joint favourites open their campaign in Johannesburg against North Korea in six days, Kaka felt one of the warmest glows he has experienced since arriving in Madrid last summer and experiencing with Ronaldo the vast weight of expectation as the new players were presented to the Real following.

In Dar Es Salaam, Kaka ran with encouraging freedom as Brazil over-ran Tanzania 5-1 on Monday with a touch and a confidence that went some way to softening Dunga's regret that the team conceded its first goal since last October. He also lasted the full 90 minutes, feeling only a single twinge in a problematical thigh.

Kaka said, "I feel good, better than for some time, but I still have to let myself go a little. There is still a little something missing but we have a week to go before the opener and I know we will all work together better. I accept my responsibilities to the team. It is quite natural that my experience in two World Cups leads to people seeing me in a more prominent position, especially with a lot of the guys from the 2002 and 2006 teams not being with us any more.

"I've worked with this group for years and I have to understand the most important thing of all is the collective effort. But within that my responsibilities are not a burden. They are the consequence of what I have achieved with the national team. It spurs me on."

There are no doubt other motivations, not least the basic pride of a man who was once voted the world's best player but in the most recent balloting came in a remote sixth, behind Messi, Ronaldo, Xavi, Iniesta and Eto'o.

Also, he has a deep personal need to avoid the fate of the Brazilian footballer who as a young man he admired more than any other. It is a story entwined in the current experience of the Brazilian team, one which many of the native cognoscenti believe has been separated, irrecoverably, from the roots of the national game.

Dunga, no doubt, has detached Brazil from the most creative and inspiring of their football, and for some it is a reminder of his influence in the Brazilian victory in America in 1994. In that team Dunga was the remorseless enforcer of competitive values. By comparison the young Kaka's hero, Rai, was the pure footballer. He was also the captain but after lacklustre performances in the group games, he was stripped of the honour, dropped and saw the band passed to Dunga.

The purists cried that a mere water carrier had taken command and was striding in the footsteps of such masters of subtlety as Pele and Gerson and Didi. Nor did it help that in the absence of Rai, who like his admirer Kaka suffered a disappointing season with a European club, Paris St-Germain, in the build up to the World Cup, Brazil achieved only a laborious victory in the final, one hugely aided by the shoot-out penalty misses by Italians Franco Baresi and Roberto Baggio.

But then Dunga asks, pugnaciously, if the nation wants to live in the glories of the past or the rewards of winning today? Certainly the coach has bred power, a quality that seemed to ooze from the big team when a weakened England were brushed aside in Qatar last November. Then, in the desert night there were mere flashes of the beauty of Kaka.

Now he knows he is obliged to produce rather more than that. His requirement is as huge as any ever faced by a front-rank Brazilian footballer. It is to rekindle more routinely the brilliance that illuminated the Olympic Stadium so compellingly but so briefly four years ago.

The likes of Messi and Rooney and Torres merely have to win a World Cup. Kaka also has to remind Brazil who they are and what they mean. It is a challenge that will demand both the highest talent and the deepest faith. Kaka insists that he is in possession of both. Brazilians, and much of the rest of the football world, can only pray that it is true.

Kaka: The statistics

Brazil & Real Madrid

Kaka scored his 27th goal for Brazil in the 5-1 win over Tanzania on Monday.

The 28-year-old was part of Brazil's winning squad in 2002 and also helped the Selecao to lift the 2005 and 2009 Confederations Cups.

Tomorrow: Argentina's Lionel Messi

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments