James Lawton: Football reverts to true status as Lampard deals with loss of mother who shaped him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

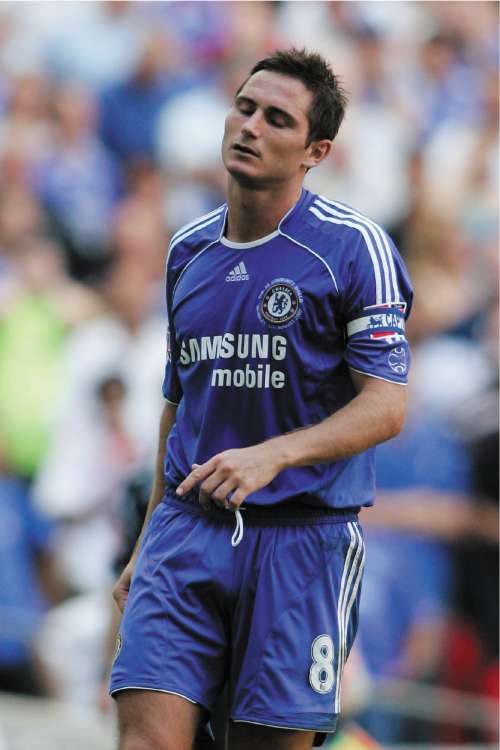

Your support makes all the difference.If the grief of Frank Lampard over the loss of his mother Pat this week tells us about anything more than the devotion of a young man to the woman who gave him his life and some of his best and most fundamental values, it can only be that the richer, and more rewarding, sport becomes the less able it seems to resist emotionally the intrusions of real life and real death.

Or, if you like, there will always be a point where sport, and all its dramas and gratifications and inflated dreams, reverts to its true status. In the end it cannot be mistaken for anything more than a sometimes compelling diversion.

It meant this week that any juxtaposition of the images of John Arne Riise, who conceded a vital goal that might prove ruinous to his club Liverpool's season, and of his Chelsea opponent Lampard, who lost the woman he insisted on calling "Number One", would have led swiftly to ridicule.

This wasn't always so. We know of old pros who in their later lives still suffer pangs of guilt that they allowed the requirements of football, its sense of importance, to outweigh pain that beyond the touchline and in less public workplaces would have commanded immediate compassionate leave.

One ex-player, a household name, recalls the bleak time he drove to join his team-mates for a Saturday afternoon game after burying the baby son who died soon after childbirth. Another admits that he has always felt uncomfortable about his feelings of exhilaration over an outstanding personal performance that came at the end of a week in which his wife had suffered a miscarriage.

You might say simply that life has changed to the point where Lampard was no more likely to receive pressure to play in next Wednesday's Champions League semi-final second leg against Liverpool, the most important game of the season so far for the club that pays him £100,000 a week, than he would be expected to travel home from an international game that had been watched by 120,000 supporters at Hampden Park, while sitting on a cardboard suitcase in a third-class rail carriage. That was what one of his predecessors of 50-odd years ago, the great Wilf Mannion, was asked to do. Lampard is saying now that he plays football on his own terms. Of course all this is right and psychologically well-ordered but perhaps what we are also seeing is that the more sport is projected, the more it is invested with ever more importance in our daily lives, the less a Frank Lampard is torn between his duty to his employers and his public and the dictates of his deepest feelings.

This is probably inevitable at a time when Test cricketers routinely fly home from the middle of foreign tours to attend the birth of a child and when the captain of England leaves the field in order to pay a visit the maternity ward.

Yesterday a friend of Lampard, the sportswriter Ian McGarry, said he thought it "unthinkable" that he would play for Chelsea on the eve of his mother's funeral. "His attachment to his mother is just too deep," said McGarry. "His father Frank was a great achiever in football and prepared him for the game with tremendous thoroughness, but it was his mother Pat who gave him a wider sense of the world."

Certainly that was evident enough in the banqueting suite of a West End hotel three years ago when Lampard accepted the Footballer of the Year award from football writers long familiar with the arrogance and self-absorption of so many of the game's leading money-earners. McGarry had given his friend some help with his speech but he too was stunned by the eloquence that poured forth. It spoke of a view of life that went beyond celebrity and to the heart of both achievement in football and an ability to remember all those things that were most important in life. Chief among these were the value of family.

His father, who played for West Ham and England, had conditioned him for the demands of football and his mother had given him so much of his humanity.

Pat Lampard had followed her son's progress in football exhaustively, she had cheered him at Upton Park and then Stamford Bridge, but nowhere was her pride more evident than in the big room which he commanded with absolute authority. "I'd suggested a bit of structure for the speech, and a couple of gags, but I was astonished when Frank got on his feet," recalls McGarry. "More than 75 per cent of his speech was his own and of course most of all it was a statement of thanks and love for his mother."

In the anguish of his reflections this week it is possible that a still young footballer who more recently has seemed less in tune with the realities of ordinary people, who complained so bitterly and indignantly when he and his colleagues were criticised for their poor showing in the last World Cup, may recall more acutely the values his mother fought to impose when she gathered him and his sisters around the family dining table.

They were, after all, the strictures which applied for so long before even an average Premier League player had reason to believe that he had inherited the world.

For some dissipation of his grief, and some girding for his competitive future, Lampard might some time soon be able to relate some of his pain to that of footballers who went before him in a time when compassionate leave would have been seen as a luxury.

You think of the devastation of Munich that came to its 50th anniversary a few months ago and which left emotional damage which in some cases will never be healed. You think of the trauma that we know went deep into the psyche of Kenny Dalglish when he spent weeks after the Hillsborough tragedy meeting the bereaved families and attending the funerals. When it was suggested that one Liverpool player, John Aldridge, should not have withdrawn from the Irish team because life had to go on and he would be better re-immersing himself in the game as he soon as he could, he said, "Yes, I know life has to go on, but how many funerals did you attend this week?"

In the meantime, Frank Lampard asserts that however important the game against Manchester United today and Liverpool next week, they must remain in the margins of his thoughts. It would not be everyone's way because everyone is different, and certainly Michael Schumacher made this clear five years ago.

The reigning world champion and his brother Ralf went to the bedside of their dying mother Elisabeth in a Cologne hospital only after qualifying at the front of the grid of the San Marino Grand Prix. They went from the track at Imola to Bologna and then flew in Ralf's private jet to Germany. Twelve hours after her death, Michael Schumacher was standing at the top of the podium. He banished champagne but it was only after the presentation of the trophy that he released, at least publicly, a single tear.

His Ferrari manager Jean Todt declared: "I think it was very important that Michael reached his own decision. Our decision was that he dealt with this in a way only he could choose. He decided yesterday with his brother to go to Germany and he definitely felt more comfortable today after having been there.

"Today, again, Michael has shown the dimension of what he is as a man and a driver."

It will probably be some time before Frank Lampard is "comfortable" but this is not to imply criticism of a man who was said always to drive with ice in his veins. It is just that Frank Lampard's blood has always run a little warmer. His decision to withdraw from football for a while might not draw any accolades from such places as the upper management of Ferrari.

He is unlikely to care. This, he would say, isn't a matter between a man and a super-powered sport. It isn't about choosing an option, or doing the right or the wrong thing.

It is about a man and his mother, and who, any longer, would dare to say that sport has any part to play?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments