Heysel disaster 30th anniversary: Liverpool have seen too much tragedy to forget that fateful day in Belgium

Thirty years ago, 39 fans waiting to watch a European Cup final died as a result of a fatal cocktail of circumstances. Ian Herbert looks at how a club that later became synonymous with Hillsborough has dealt with this tragedy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

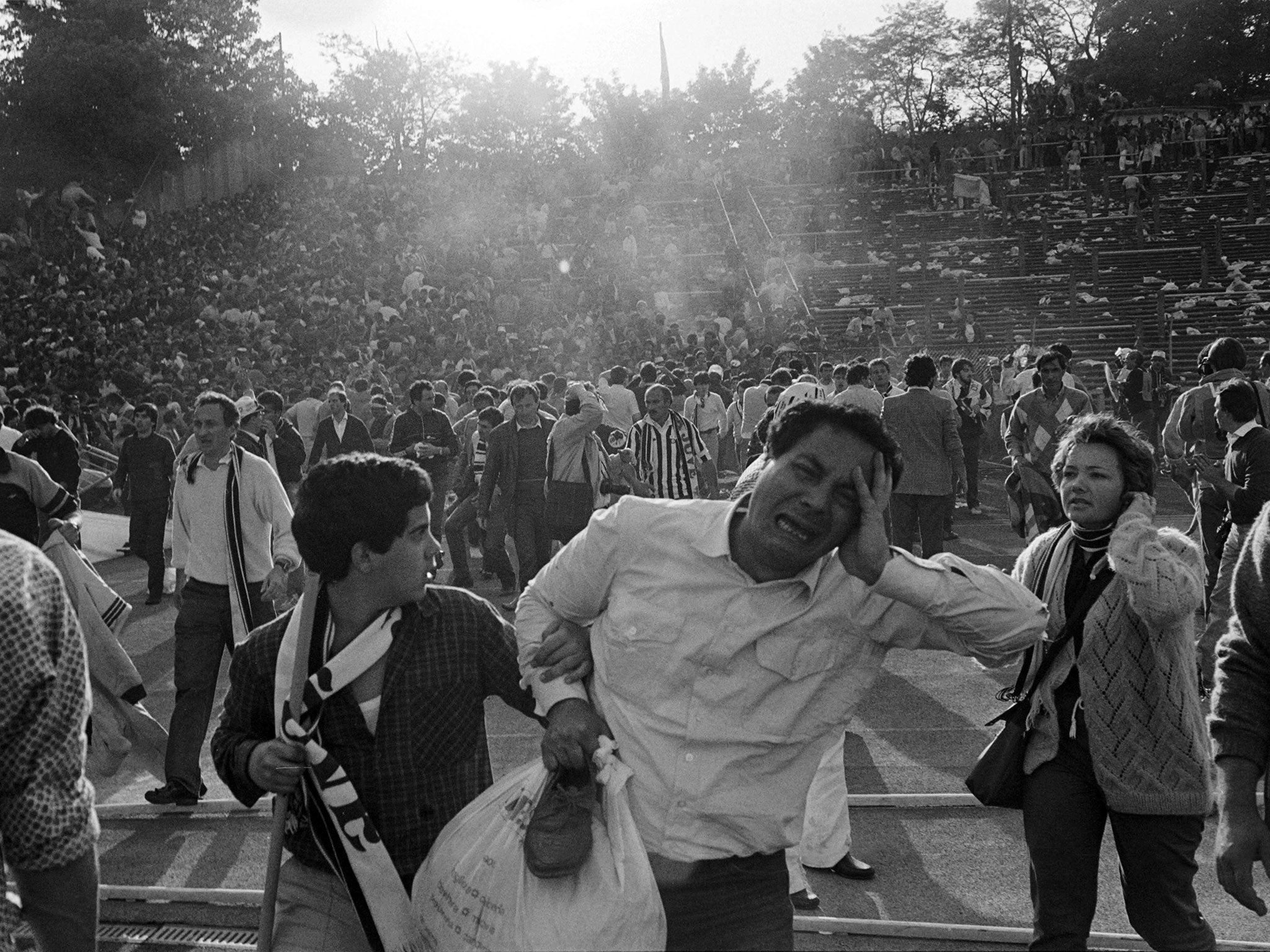

Your support makes all the difference.It is 30 years since they reached the Heysel stadium and draped such banners as Mamma sono qui (Mum, I’m here) over a crush barrier in the naive assumption that the build-up to the European Cup final between their team, Juventus, and Liverpool might be something their mothers could watch, proud that their boys had completed the 10-hour road trip north. “Uefa and the Belgian FA wish you a hearty welcome in the Heysel Stadium,” read the message on the primitive electronic stadium screen when fans walked in that night, another sign of confidence that it would be a standard football evening.

It was not, of course. The banners were of not the slightest significance to the mothers back in Piedmont who stood transfixed before TV sets, looking for a sign in the transmission that their own flesh and blood was not caught up in the crush which killed 39 people – 32 of them Italian, four Belgian, two French, one Northern Irish. The German ZDF broadcaster terminated its transmission out of a respect to these people before the decision was taken – astonishing and abysmal in hindsight – that the game would still be played that very night: a 9.40pm kick-off, with the deaths so quickly put out of mind that the noise of the crowd could actually be heard from the little Brussels hospital where many of the bereaved had congregated.

The tragedy was an awkward truth for Liverpool FC for years and is certainly an indelible stain on the club’s reputation, with an initial struggle to take responsibility which sat uneasily with the brave and indefatigable fight for answers and transparency about the 1989 Hillsborough disaster.

The Liverpool Echo of 11 June 1985 carries an image of then editor, Chris Oakley, bearing some of the 120 letters the newspaper received from fans, beneath a headline capturing the shame of one anonymous writer. “As far as I was concerned it was just a fight but look now: 36 dead,” he wrote, the death toll yet to peak. “Oh God, I’m sorry. Before the game drink was freely available and yes I drank.” He writes of an attack on him by an Italian while outside the ground. “By the time I got into the ground I was drunk, and inside blamed all Italian fans for the attack on me. I was boiling up inside.”

Even back in Britain, they did not know what calamity they had left in their wake. Heysel: the Truth, by Italian journalist Francesco Caremani, reveals that it was open newspaper testimony such as this which convicted Liverpool fan Terry Wilson, an 18-year-old at Heysel.

An illuminating and unflinching extended new discussion of the tragedy on the Anfield Wrap podcast has provided a broader sense of the tragedy from a Liverpool perspective, too. The context of Liverpool facing Italian opposition only 12 months after running a gauntlet of violence by AS Roma fans, before the European Cup final the club won on penalties, is not offered in justification of what happened on that unseasonably hot night in Brussels – but it clearly impacted on the Liverpool mindset. “There was a more defensive attitude because of it,” the writer and Times journalist Tony Evans says.

Both he and former BBC Newsnight journalist Peter Marshall, who was at Heysel to chronicle the Liverpool supporters’ conduct on the 1985 final for BBC News, attest to the copious amounts of drink the English consumed. There was to have been no drink on sale near the ground, yet by 5pm every kiosk and bar was selling strong Belgian beer to anyone and everyone in the Liverpool contingent. The consequences were inevitable: some fans paralytic with drink and the usual sources of inbuilt restraint incapable of their usual influence on a Liverpool fan base actually widely acknowledged as better behaved than most on the Continent at that time.

The usual wild rumours that could set in to football crowds on the Continent in those very different days were beyond all sense. Evans relates there was a rumour of a Liverpool fan having been hung from a tree doing the rounds that night. “There was more belief in rumours. The normal restraints were gone,” he tells the podcast. Film from that night reveals that the violence was no one-way street, with footage showing a Liverpool fan being hacked at by a Juventus supporter with a baseball bat, struck across the top of his head by a rock and then pursued by a baton-wielding police officer, all within a 10-second clip. But one banner suggested Liverpool fans had a pre-conceived notion about what they would encounter: “Reds [v] Animals” it proclaimed.

That drink should have been so freely available was part of that very familiar 1980s story of institutional failings at football matches. The game took place in a stadium built in the 1920s which was patently unfit for purpose. The perimeter breeze-block wall was full of crevices big enough for fans to enter. It faced an open construction site which provided ready missiles. There were minimal police available to undertake specialised public-order duties, not least because all overtime had been exhausted by Pope John Paul II’s visit a month earlier. Marshall describes police simply running away when Liverpool fans challenged them. “That was part of the context, though not a defence, not an explanation,” he says.

It was that extraordinary decision to play the game, resulting in the now Uefa president Michel Platini dancing round Heysel’s perimeter track on the night that 39 poor souls died, which also sits most desperately with Liverpool supporters. Peter Hooton, the musician who has done much to salve the relationship between the two clubs’ fans, represents very many of their number in saying he would have walked out of the stadium had he known the enormity of what had happened. The decision to play was made by apparatchiks amid chaotic deliberations in a VIP area below the stadium.

Ian Rush, who played for both clubs, will attend a commemorative mass at the church of the Gran Madre di Dio in Turin, while the Liverpool club chaplain the Rev Bill Bygroves will lead a private memorial ceremony at Anfield’s Heysel memorial where Phil Neal, club captain that night, will lay a wreath. The process of remembrance has not always been easy but Liverpool has known too much tragedy to forget.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments