Football's charitable status: Philanthropists in the Premier League

If stories about players giving generously invite cynicism, the one about Craig Bellamy setting up a £650,000 academy in Sierra Leone was met with disbelief. But, writes Glenn Moore, such responses are often unfair and there is much to applaud in this modern sporting trend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A certain cynicism usually descends whenever footballers' charitable projects are mentioned. For many people, a sport which pays its elite participants tens of thousands of pounds a week is never going to invest enough in the wider community. When it does contribute to society, the gesture is frequently dismissed as a publicity stunt.

Sometimes this is justified. Last season Chelsea made a donation to the agencies – two hospitals and a brain injury charity – which saved Petr Cech's career, maybe his life, after the goalkeeper's head injury at Reading. Timed to co-incide with their FA Cup final press day, when dozens of reporters and photographers were at the club's training base, Cech presented three outsize cheques, the sort used by pools companies, for £1,000 each. The money came not from the player, who is paid in excess of £50,000 a week, nor from the club, which has spent £400m-plus on transfers in five years, but from supporters who had bought photographs of Cech. It was so embarrassing most reporters kept well clear.

Chelsea can justifiably point out they have helped raise more than £1m for their national charity partner, CLIC Sargent, in the last two years, money which makes a real difference to the children's cancer charity. Like many clubs, they also have a well-resourced football in the community scheme. A 2005 audit by Deloitte & Touche put the community spend of Premier League clubs in excess of £80m a year. Clubs were, nevertheless, criticised last year for their limited cash donations by the charity advisory website intelligentgiving.com (the bulk of Chelsea's £1m contribution to CLIC Sargent, for example, has been raised through "leverage", giving their name, or players' time, to encourage others to give cash). As Dave Pitchford, one of the founders, said: "The most useful thing to charities is hard cash. Celebrity visits and free [or subsidised strips] are valued, but they don't pay the bills." And they don't cost much.

Given this backdrop, Craig Bellamy's involvement in Sierra Leone, announced yesterday, is truly remarkable. The West Ham striker, previously best-known for a string of controversial incidents at both football clubs and nightclubs, is to invest £650,000 of his own money into creating an entire football structure in the benighted west African nation.

There would be less surprise if the player were Aston Villa's Nigel Reo-Coker or Liam Rosenior, of Reading, as they are of Sierra Leone descent, but Bellamy knew nothing of the country before travelling there in June, alone but for a big bag of footballs. Liverpool, his club at the time, even refused to insure him, Sierra Leone having only recently emerged from a civil war which required the intervention of British troops. It also ranks bottom in Unicef's measure of child mortality and of the United Nations' Human Development Index.

Bellamy initially decided to set up an academy. Tom Vernon, Manchester United's scout in Africa, who is involved in a similar project in Ghana, conducted a feasibility study. His conclusion was that Bellamy would have to create a youth league as well, as there was no way of assessing potential academy recruits at present. Thus, in six months it is hoped 14 leagues, involving 68 teams, will begin. As part of the initiative, coaches will be trained while children will be taught HIV/Aids awareness and encouraged to go to school. Their teams will be rewarded in each case with league points.

Bellamy stressed he will not be making money out of the scheme. Africa is littered with "academies", many run by agents who are mainly interested in selling players to Europe. Bellamy's scheme is more akin to Diambars, the Senegalese academy founded by Patrick Vieira, former Hammers' goalkeeper Bernard Lama, ex-Hibernian's defender Jean-Marc Adjovi-Boco and local player Saer Seck. Like Diambars, Bellamy intends to educate the students in more than ball skills so those graduates who fail to find footballing employment emerge equipped to play a role in developing the country.

While most footballers remain more interested in building a designer mansion in Cheshire or buying an even faster sports car, Bellamy's altruism is part of a slowly growing trend. Robert Green, one of Bellamy's team-mates at Upton Park, is going to Uganda this summer to work with the African Medical Research Foundation.

It is a long way from the cheesy visits to hospitals at Christmas time (which, incidentally, still go on and are much welcomed by the children involved) and reflects the growing financial power of footballers and their greater worldliness, a by-product of the globalisation of the Premier League.

Foreign players have been setting up foundations for some years. Juan Sebastian Veron funds a school in La Plata, his home city in Argentina; Ulysses de la Cruz, Reading's Ecuadorian defender, has financed infrastructure development in his home village; Pavel Nedved provides money for football schools in the Prague area and donated his match fees when appearing for the Czech Republic to charity; Brazilians Rai, Leonardo and Cafu helped develop the Milan Fundacao – the latter two played for Milan – which helps youngsters in the Sao Paulo favelas. The man who has gone furthest is Damiano Tommasi, Levante's former Italy midfielder, who, besides making a significant financial donation, spent an off-season helping to build low-cost housing for immigrants in Italy.

It is not just the top (ie, wealthiest) footballers who put something back. Mickey Evans was a journeyman footballer, primarily for Plymouth Argyle, whose brief Premier League career with Southampton will not have made him rich. Nevertheless at his testimonial last week he followed the example of fellow Republic of Ireland internationals Niall Quinn and Gary Kelly, who donated their testimonial receipts to charity, in passing on three-quarters of his proceeds to local charities.

What motivates Evans, Bellamy, Tommasi and the like? The same reasons, in all probability, as the general public. Donating time or money to charity usually makes people feel good about themselves, the more so if, like most footballers, they have been dealt a fortunate hand in life – Quinn said he was partly motivated by "guilt". A few may have a political or religious motivation, some have a personal interest. Following the loss of Jake, his four-month-old son, from cot death, Jody Craddock, the Wolves defender who has a successful sideline as an artist, donated work and football memorabilia to the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) charity. What can largely be ruled out, with reference to individuals if not necessarily clubs, is a desire for good publicity. As Vernon said of Bellamy: "There are a lot cheaper ways of getting good publicity than this."

Besides, many football people do charitable works on the quiet, which is one reason why last season's Mayday campaign, which asked footballers to give up a day's salary to help nurses, had a mixed response. Gareth Southgate, the Middlesbrough manager, blocked the club's donation after the campaign organiser, Dr Noreena Hertz, listed who had contributed – effectively "outing" those who had not.

Almost implicit in the campaign was the sense that footballers were undeservingly wealthy. Why not target executives in the FTSE 500? Or City fund managers? Similarly, why did intelligentgiving.com pick on football clubs and not oil or pharmaceutical companies, or banks? Salaries in, and profits of, these companies are often on a par with elite footballers, but footballers, with their well-publicised affection for Cristal champagne and £1m weddings are a soft target.

The Premier League, backed by Barclays, have responded to the growing cynicism about footballers with a series of community charity initiatives. Critics will note these are usually accompanied by newspaper or broadcast media coverage. But as the minority of daft footballers who live to excess get disproportionate coverage, trying to redress the balance is understandable, wise even. For while it is true that most players are self-obsessed, an increasing number are realising that their celebrity and wealth gives them power to change people's lives for the better. What is startling about Bellamy's project is its ambition, and the protagonist's identity. The striker's bad-boy reputation may even be a good thing; if he can get involved in something like this, charity is not just for goodie-goodies.

Doubtless yesterday's revelation will enhance Bellamy's image. Being involved in it will probably make him a more contented person. But the people who will benefit most will be the boys of Sierra Leone. All power to him.

Highlights and low points from Bellamy's eventful past

Craig Bellamy would not be the first name to come to mind when thinking of sportsmen and their charitable concerns. Indeed, he may figure nearer the bottom of any list of role-models, given the colourful career of a player Bobby Robson described as "a man who could start a fight in an empty room".

Bellamy started his league career at Norwich, coming through the youth system after failing a trial at Bradford. Notable exploits on the pitch, including a debut for Wales, were matched by his boisterousness off it, highlighted by the four hours he spent locked in a coach toilet after team-mates grew tired of his whining.

An average season at Coventry ended with a £6m move to Newcastle, where controversy followed. A falling out with Graeme Souness hit the headlines in 2005, when the then manager omitted Bellamy from the team to face Arsenal after claiming he refused to play out of position, a claim Bellamy denied. He was sent to Celtic on loan after turning down a move to Birmingham, claiming "I am Craig Bellamy and I don't sign for shit football clubs."

The Welshman became further estranged from St James' after abusive text messages were allegedly sent from his phone to Alan Shearer after a Cup defeat, another claim the forward denied. A season at Blackburn was interrupted by an incident in a Cardiff nightclub where he was accused of assaulting two women, charges of which he was cleared.

His most infamous misdemeanour occurred while at Liverpool, as the side prepared in Portugal for a Champions League match with Barcelona. His team-mate John Arne Riise was attacked with a golf club as he slept after refusing to take part in a karaoke session. The "Nutter with a Putter" then celebrated a vital goal in the Nou Camp with a golf swing before setting up Riise for another goal. A move to West Ham followed, where he has endured an injury-plagued season.

James Mariner

Good sports: The athletes who made money for charities

IAN BOTHAM Former England cricket captain

Has taken part in series of charity walks, raising over £10m for various causes, mainly Leukaemia Research.

JEREMY GUSCOTT Former England rugby union international

Followed in Botham's footsteps, taking part in a charity walk across Britain for Leukaemia Research.

ROB GREEN West Ham goalkeeper and Independent columnist

Will attempt to scale Mount Kilimanjaro this summer to raise money for the African Medical Research Federation.

LUCAS RADEBE Former Leeds United and South Africa defender

Is an ambassador for the SOS Children's charity in South Africa.

NEIL HARRIS Millwall striker

Was diagnosed with testicular cancer in 2001, and set up the Neil Harris Everyman Appeal to fight the disease.

GEOFF THOMAS Former Crystal Palace, Nottingham Forest, Wolves and England midfielder

Was diagnosed with leukaemia in 2003, after which he raised over £150,000 for Leukaemia Research by cycling the 2,200 miles of the 2005 Tour de France in 21 days. The Geoff Thomas Foundation raises funds for cancer treatment.

BOB WILSON Former Arsenal goalkeeper

Set up the Willow Foundation with his wife following the death of his daughter Anna from cancer in 1998, aiming to provide a better quality of life for seriously ill young adults.

ADAM HOLLIOAKE Former Surrey cricket captain and England all-rounder

After his brother Ben was killed in a car crash, he set up the Ben Hollioake Memorial Foundation, for whom he raised money with a walk, cycle and sail from Scotland to Morocco.

JOHN AMAECHI Former basketball player for Orlando Magic, Utah Jazz and England, now a broadcaster

Received an honorary doctorate in science for work with the National Literary Trust, the NSPCC and the ABC Foundation, which he set up to get children playing sport and increase their contact with support services.

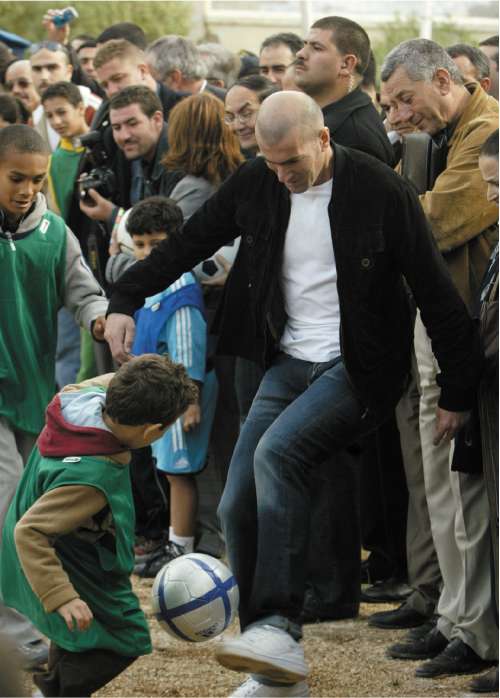

ZINEDINE ZIDANE Former Juventus, Real Madrid and France midfielder

Helped to set up the annual Match against Poverty, which fundraises for the United Nations Development Programme.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments