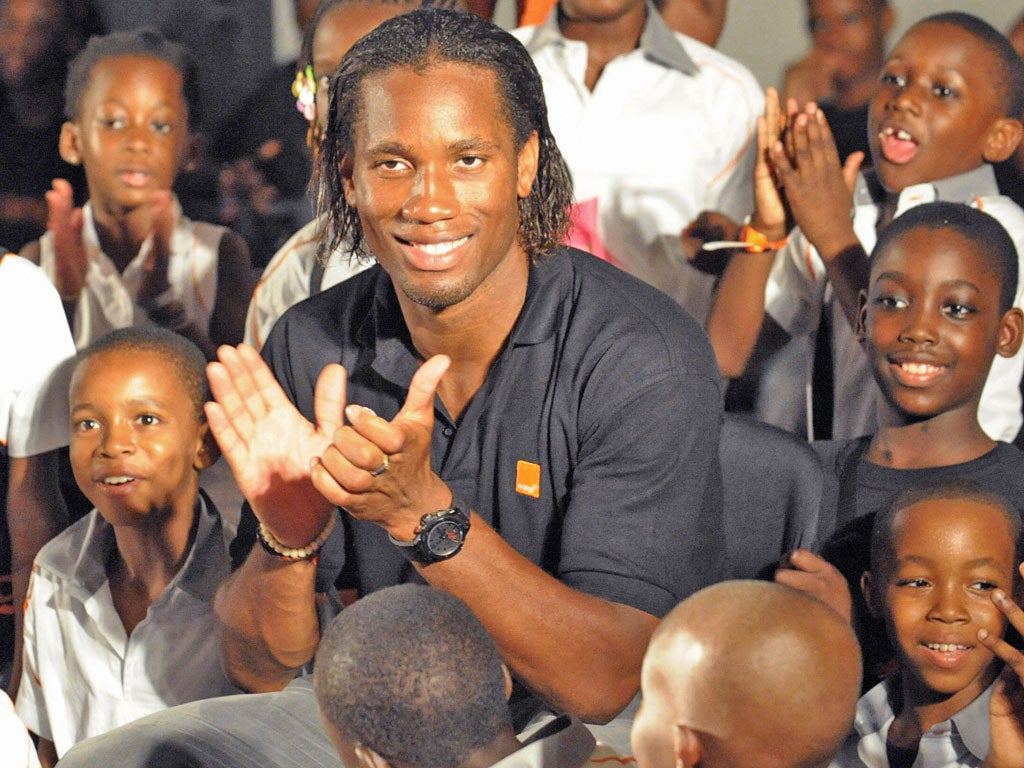

Drogba heals the wounds of civil war in homeland

Chelsea striker is a growing influence beyond the playing fields

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At 34 and counting, Didier Drogba may be drawing to a close his career at the highest level but there were moments during the closing stages of Chelsea's reinvigorating victory over Manchester City on Monday night when he issued a blunt reminder of the power that remains. As the clock ran down, Drogba galloped with the ball into City's half, effortlessly holding off the attentions of desperate opponents, the Ivorian's strength and determination plain to see.

Power has been an instrumental part of Drogba's make-up and his success in utilising it on the field has brought growing power and influence off it. In this country, Drogba divides opinion; on one side there are Chelsea supporters, on the other the rest of English football. It is not an equal split. But away from the game he has become a unifying figure.

Earlier this month he was selected for a global humanitarian award; earlier this year he was chosen to become one of an 11-strong Truth, Reconciliation and Dialogue Commission, based on the successful South African model, to try to help heal the wounds of this year's civil war in his homeland. "If I wasn't optimistic I wouldn't be there," said Drogba, speaking about his appointment in September to represent the views of his country's diaspora. "It's the first step. We want peace to last, not to be just words, and it's important that after this situation people can be able to sit together, speak and think about why we ended up with a civil war."

This year's brief but bloody division, in which more than 3,000 were killed as violence erupted in the wake of disputed elections, was the second civil war to devastate the country within a decade and Drogba has been a leading and willing figure in trying to bring each to an end. Football has played a unifying role in Ivory Coast. In 2007, Drogba pushed for a qualifier for the African Nations Cup to be played in Bouake, the rebel stronghold. That came a year after Drogba and his team-mates dropped to their knees live on television in the dressing room shortly after the national side had qualified for their first World Cup in Germany and pleaded with the warring factions to talk.

"We had just qualified for the World Cup," said Drogba, "and all the players only wanted one thing – Ivory Coast to be united. The country was divided in two, but we knew we were calling people in the country and they were saying, 'When Ivory Coast is playing the country is united. People who don't [normally] talk to each other, when there is a goal they celebrate together.' We were trying to use this and send the message to our politicians to sit down and talk and try to find some solutions.

"I knew that we could bring a lot of people together. More than politicians. The country is divided because of politicians; we are playing football, we are running behind a ball, and we managed to bring people together."

His role has been praised by Tony Blair, now chairman of ambassadors for Beyond Sport, the body that gave Drogba the humanitarian award. Blair describes Drogba as "a powerful, articulate persuader". Blair said: "Sport can reach parts politicians can't reach. It can help in bringing divided conflicts together in a way nothing else can."

Drogba was born in Abidjan, the capital, and grew up partly there and partly in the care of his uncle, a lower league footballer who played in France. Drogba too learnt his trade there, turning out for Le Mans, Guingamp and Marseilles before crossing the Channel seven years ago, but there has never been a question as to where his loyalties lay. Now his country's record goalscorer, with 50, and the figurehead of the best team Ivory Coast has assembled, he has become the nation's most recognisable figure. "People want to say, 'Didier is going into politics, that this is too complicated for him'. But it's not, it's not," says Drogba as part of a BBC documentary made by Christian Purslow, Liverpool's former chief executive, exploring football's influence beyond the playing field. "It's just a kid from Côte d'Ivoire who wants to help his country. I am not a politician, I will never be. But if I can help my country I will do anything.

"I'm not here to judge the ex-president or the new one. The only thing I can say is that the population suffered a lot. A lot of people have been killed. That's why it was necessary for us to speak. I've suffered from this war but it's easy for me to come out and say 'My village has been attacked' or 'This guy from my family died'. But what about the others? The other people who cannot talk. They all suffer."

'Urban Legends: Can Football make a Difference?' is on BBC 5 Live this evening from 7.30pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments