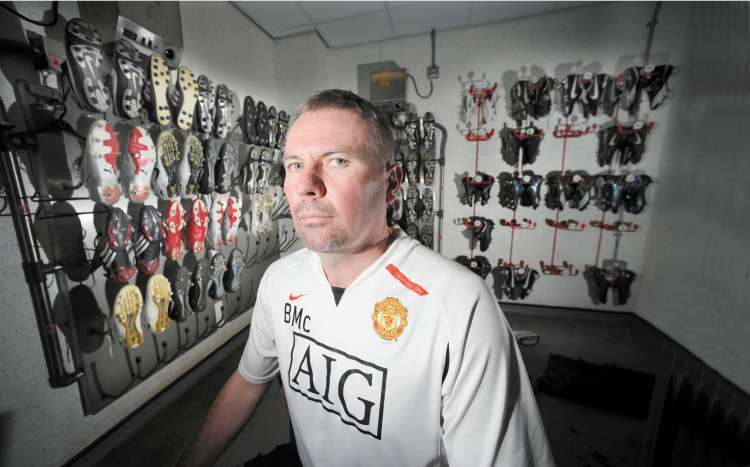

Brian McClair: 'We won't produce a group like Beckham, Butt and Scholes again'

As a player Brian McClair watched a golden generation of young Red Devils make their names. Now head of Manchester United's academy, he tells Sam Wallace why he is struggling to develop similar English talent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The business of dominating English football never stops. Which means that even if they beat Wigan tomorrow to seal their 10th Premier League title, Manchester United will ask themselves the big question: what next? Central to United's dynasty of success is the production of young footballers which, in the 50th anniversary year of the Munich air disaster, has never been quite so poignant.

It is almost 13 years since Sir Alex Ferguson put his faith in a famous generation of young players: David Beckham, Gary Neville, Paul Scholes and Nicky Butt. Ryan Giggs was already on the scene. Phil Neville was two years younger. The following May, in 1996, the unfancied kids won the title, all of them home-grown, all but one from Greater Manchester. Their success is one of the parables of the modern game and, as United contemplate another summer in the bull market of international transfers, it is a time that seems ever more to belong to a distant era.

Will United ever produce another generation like that? Will any English club? Brian McClair, head of United's academy since 2006, is probably sick of being asked the question. Behind the scenes of English football, in its most powerful clubs, the question of how young players are being developed is changing fundamentally. A whole new system – the Premier League-designed academy structure – has been in place since 1998 and it is not universally popular. When asked about the issue, Ferguson will often reply that he needs an entire press conference to answer. So here is a simple opening statement that puts it in perspective.

When McClair is asked when the next Scholes or Giggs or Beckham is coming, he answers thus. If the current academy system had been in place in the late 1980s United would not have signed Beckham, who grew up in Essex. McClair does not believe they would have signed the Nevilles either, as they would have been snapped up by Bury at an early age and a prohibitive price put upon them. Scholes, he says, would have been at Oldham Athletic's academy. Giggs would not have had the chance to leave Manchester City for the club he supported. United might have got Butt; they might not.

"It was a perfect example of why that system worked," McClair says. "United were very good at getting all the local boys and they got out-of-town boys to come on their holidays. If you look at that group of players who won the 1992 FA Youth Cup for United, nearly every single one of them played at the highest level because they were the best from Northern Ireland, they were the best from Wales, the best from England, the best from Scotland. You can't compare anything to the Beckham, Butt, Scholes generation with what happens now. It's impossible to do that now.

"In 1995, the first team was world-class, but we weren't competing at the level they are now. Maybe United didn't have that wealth, so the manager looked at the young players and said, 'Let them have a go'. There was an opportunity and sometimes you only get one chance. That summer Andrei [Kanchelskis] left, Incey [Paul Ince] left, Sparky [Mark Hughes] left and Paul Parker was dithering over a new contract. He dithered and suddenly Gary [Neville] had taken his place in the United and England team. How good were these boys? Nobody knew. We had played with them in the reserves, and they looked good enough. They took their opportunity."

Since then United have scored some successes. Wes Brown, John O'Shea and Darren Fletcher have become established squad players, if not superstars, having come through the youth teams. The Spanish centre-back Gerard Pique, acquired from Barcelona to be part of United's academy, is on the brink of the first team. Speak to those in the know and they say the 17-year-old striker Danny Welbeck, who was on the bench for the Champions League semi-final against Barcelona, has the best chance of the current crop.

The basic principle of the academy system – that clubs can only recruit boys up to the age of 11 who live within an hour's travel of their academy base – is one for which Ferguson has a long-standing antipathy. It means that the comprehensive scouting network he built up in his first decade at Old Trafford, the one that brought Beckham from Essex, was rendered virtually obsolete overnight. The arguments about academies go right to the heart of the debate about English football and where its next generation of players will come from.

From McClair, the head of the academy of the most famous club in the world, there are some radical suggestions for change. He would like a central academy where the country's best 16 players – regardless of their club affiliations – train with each other all year round. He would like boys to be able to leave one academy for another at the end of each season without punitive transfer fees for the clubs they join. And he would like changes to a system that imposes "parochial" limitations on a club that has to draw its players from a small pool in the North-west yet competes on a European scale.

McClair is also a realist. He knows that United and the other big clubs cannot simply have it all their own way and scoop up all the best players. He accepts that the academy system has not been all negative – it has meant a universal rise in standards in facilities and coaching and United, like other clubs, still put enormous effort and resources into developing the young players they have. However, top English clubs are filling their academies with foreign youngsters because it is easier, not to mention cheaper, to sign Parma's best young talent than it is to get a comparable English teenager from Devon or Kent.

What job could be bigger than developing young players good enough to play for Ferguson? Before he became Ferguson's first high-profile signing in 1987, McClair was rejected by Aston Villa. In his early career at Motherwell, and later Celtic, he completed a maths degree at Glasgow University that gave him a grounding outside football. As the man whose job it is to break bad as well as the good news to hundreds of young hopefuls, McClair weighs his words carefully. You can see why Ferguson rates him so highly: he is a bright bloke who has to make big decisions about young players – and no big decision at United is ever taken lightly.

McClair's first problem: United pick their players at eight – "a career-defining decision," he says – and stick with them until they are 16, when a decision is made whether to offer them a two-year "scholarship" contract. In recruiting eight-year-olds they compete with all the other teams in their catchment area, and that direct competition is staggering: Manchester City, Liverpool, Everton, Blackburn, Bolton, Sheffield United, Sheffield Wednesday, Crewe, Leeds and Huddersfield.

"If you look at the parallel for education, parents are free to choose whatever school they want their kids to go to, whether they have to pay for it or move to a certain area," McClair says. "You can't in football. If they move at all, and their child goes from one academy to another area, they have to show they are moving for non-football reasons. That will take a lot of time to clarify and the kids and parents are penalised by that."

The trend among the young players that United see is that, if they do not get selected for United's academy aged eight, they tend to go elsewhere. It means that United cannot return to check on their progress in a couple of years' time because the norm is that those boys will be signed to another club's academy and will therefore be out of reach. Sometimes, as in the relatively recent case of Kieran Richardson, United will make an offer to sign a player from another team's academy, but this is an expensive business.

"If you take a boy without agreeing compensation you are forced to go to tribunal and we have found in the past that the values they put on players we had signed were unfair," McClair says. When it comes to signing 16-year-olds from within the European Union, the price is dictated by Fifa regulations, which generally make it cheaper for clubs than paying compensation to rival English academies. Little wonder that Chelsea, Liverpool and Arsenal are luring 16-year-olds to their academies, presumably with the promise of lucrative contracts. United still have a majority of British players in their academy, including the sons of McClair and the chief executive, David Gill.

The received wisdom about youth teams was that clubs signed 15 boys so the one player with a chance of making it had a team to play in. McClair is justifiably proud of the volume of players who, having failed to make it into United's first team, have made careers elsewhere. Still, the cream of English players are scattered among the clubs, training with less talented peers from the age of eight to 16; if they were training as an elite, centralised group, McClair says they would enjoy a greater improvement. In France, the clubs send their best players to one of a group of regional academies that includes the famous Clairefontaine, outside Paris.

"If you have all the best players at all age groups playing and training together they get better," McClair says. "If you had all the best players in the North-west at one academy you [would] not have, for example, Liverpool's best player training with the next 11 or 12 players they can find. It's going to be the 16 best boys training together and playing against the other nine academies. It would be an elite thing. It's the right system if you want to improve English players."

United fish in what McClair believes is an ever-dwindling pool of talent. "There are fewer boys playing football," he says. "I'm not sure I would have been out in the pouring rain kicking a ball all the time if I had a Nintendo Wii at home. It's a natural thing."

Players are signed or rejected by academies at the ludicrously young age of eight and, by and large, there is no room for error. "Kids should not be tied to an academy at eight years of age," McClair says. "Up until 14, at the end of every season they should be allowed to choose whether they want to move."

That would benefit United and the bigger clubs but also, ultimately, the England team. In July last year a review of the academy system commissioned by the Football Association, Premier League and Football League was published. It was undertaken by Richard Lewis, the executive chairman of the Rugby Football League, who McClair says did a "first-class" job. United agree with all of Lewis's 64 recommendations, which include relaxing the rules on where players can be recruited from. Unfortunately, nine months on, there is still a squabble between the FA and the Premier League about who should be on the committee to implement the report.

"Because of procrastination nothing will change for next season," McClair says. "People are crying out about England not qualifying for Euro 2008 but nothing is going to change now for a least another season. There are still people at the top of the game who aren't interested in the development of kids. The fact is that nothing is done about this, that they are arguing about the make-up of the committee."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments