Bradford vs Reading FA Cup preview: Thirty years on from the Valley Parade fire, Bradford’s story starts to be told

It’s football’s forgotten tragedy but a play is reawakening the events of that afternoon in 1985. As the club contemplates an FA Cup quarter-final Ian Herbert speaks to those involved on that fateful day and those helping to finally tell the tale

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If you are looking for a team whose fortunes to follow in this FA Cup weekend of the largely usual quarter-final suspects then bear witness to Martin Preston’s story about the silence and it will be Bradford City.

You imagine that there would be noise, screams, sound and fury if you found yourself caught up in a disaster the likes of which befell the club, 30 years ago this spring. But it is the utter absence of noise that has always remained with Preston about the moment when he found a football fan running towards him across the Valley Parade pitch, his body on fire. “I remember it as a silent episode,” he says, sieving through the years and the fragments of memory of how he – then a young police officer – computed what to do in that enormous moment, as the man ran from the fire ripping through main stand. “It was like a scene you see in Hollywood: this burning figure...”

Those were very bad times for football, the lumps of concrete that littered the ramshackle stadium terrace were regularly used as missiles and suddenly Preston found a young man alongside him ready to help those who were suffering. He was what Preston – and perhaps you – might then have called a football hooligan. “Black top,” he remembers. “He wore a sleeveless black top. It was a lovely spring day. I’d bollocked him and kicked him up the arse 15 minutes earlier. So we knew each other. I remember being there, with that man who was in flames, and the young lad telling me: ‘You’re not kicking me up the arse now, are you?’”

They were in the goalmouth by then and the fact that there was nothing to put the flames out with is not something the two of them actually thought about. They found an instinctive way to help the man. “We picked him up together and rolled him on the turf,” Preston remembers. “Rolled him like a rolling pin and that put the flames out. Then we left him for someone to take out. The next thought was: ‘Right, we’ve got to get another.’”

Preston doesn’t know where that supporter who helped him went. He vanished into the maelstrom at some stage and Preston has never seen him since, though he has always wondered who he was. A photograph of the two of them carrying that fan was printed in the Bradford Telegraph and Argus. “My mother kept it for years,” he says.

The officer has other memories of what he thinks might have been 30 minutes in that hell. The supporter near the home dugout, unreachable because of the sheer heat of the fire, who staggered to his feet but fell back into the flames. The significance of the light breeze which picked up the flames and carried them “like a bush fire” across the length of the old stand. The sensation of his nylon shirt melting on him in the heat. (“I never wore a nylon shirt again.”) And later, after his forehead had blistered in the heat of the rescue, the boy in the ambulance with him on the way to the St Luke’s Hospital – perhaps 10 years old; no more than 11. The boy asked him: “How did Leeds get on?” when the vehicle stopped at the lights outside the Mecca ballroom. “How could you help him?” Preston asks. “You couldn’t say ‘what’s your dad’s number, or your grandad’s?” The boy survived. His father did not.

The extraordinary part of all this is that testimony has barely been heard. Preston has related it all perhaps four or five times down all these years and that is because the Bradford Disaster, which claimed 56 lives, has remained largely unknown. It is a story to make you rage against football’s breathtaking complacency. The fire took hold because the safety of the stand was so monumentally neglected that a charred copy of the local paper from Monday 4 November 1968, was among the debris beneath the terrace which caught fire. This, at a time when the club had a turnover of more than £600,000 – enough to make their stadium safe – but chose to blow nearly £420,000 on wages to chase the promotion from the old Third Division which was being celebrated that day. But the city just took the damned negligence for what it was – a part of those times. Justice Oliver Popplewell’s inquiry was quickly concluded and though there is a positive legacy – Bradford specialist burns unit was created out of the tragedy – it has remained a largely untold story.

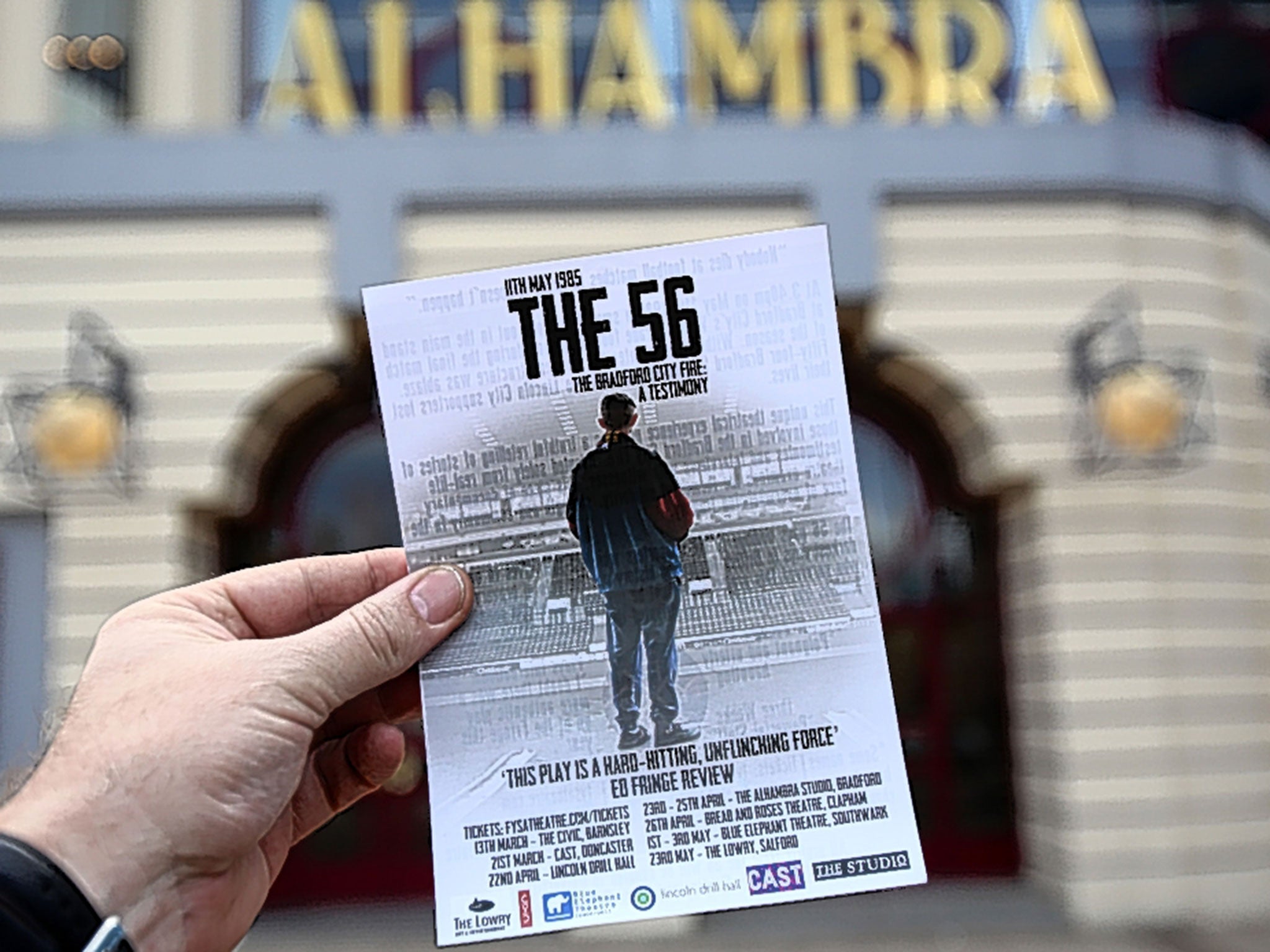

There is an obvious and most beautiful significance about Phil Parkinson – an enlightened, articulate young football manager – taking Bradford to the quarter-finals, and perhaps beyond, in this anniversary year of all years, though it has not taken the vagaries of Cup football to help the city remember. The testimony of former officer Preston – who retired from the West Yorkshire force in 2008 and is now 55 – is one of over 50 which form part of a play – The 56 – which had a remarkable impact at the Edinburgh Fringe last summer, has collected four- and five-star reviews and has been shortlisted for the Amnesty Freedom of Expression Award. It will begin its run through the regions at Bradford’s Alhambra Theatre on Friday.

The script, which traces 11 May 1985 through the eyes of three supporters, is taken from verbatim interviews carried out by director Matt Stevens-Woodhead. At the age of only 22, he has covered an extraordinary amount of ground and displayed a remarkable level of persistence. After the Edinburgh success, word spread about this project and Stevens-Woodhead spoke to Terry Yorath and John Hendrie, who coached and played for Bradford that day, Lord Justice Popplewell, Professor David Sharpe, who set up the burns unit. Their testimonies have made the script even richer now than it was at Edinburgh.

Though the people of Bradford do not ask for comparisons with those who have suffered intolerably since Hillsborough, Stevens-Woodhead – who has sought and received advice from the verbatim theatre form’s best practitioners, David Hare and Richard Norton-Taylor – was set on his course by an encounter with a supporter at the Hillsborough Stadium’s annual memorial service for the 96 Liverpool fans. Stevens-Woodhead, whose co-director Gemma Wilson is a Bradford City supporter, found fans of the club who had never been to the theatre travelling to Edinburgh to see this performance. “It was a way of connecting a new generation to what happened that day,” he says.

The power of the stories resides in their understatement. Details like those fragments recalled by Mick Spencer, a police officer who had seen the plumes of smoke in the skies from his home in the city’s Ordsall district – where he was on a Saturday off, gardening – when he was called in to man what they called the “casualty bureau”.

An encounter with one of the first men to stagger up to his simple desk at the Bradford Royal Infirmary – “burned black, his hair all taken away by the fire, clothes obviously burned to his body ” – is the one which has always lived with Spencer. Because of the nature of burns injuries, this individual didn’t seem to be in pain. “The initial agony doesn’t persist. It is the trauma of the skin healing which is the fatal part,” Spencer relates. And so it was, amid the horror in which he had been caught up, this man actually cracked a joke. “He said to me; ‘Will you tell my wife that I don’t want toast in the morning!’” Spencer recalls. “I took down his name, he went away for treatment and that was it.” He was Jim West, one of the two Lincoln City fans, who lost their lives that day and whose names have given Valley Parade its Stacey-West Stand, to this day.

Some desperate encounters were to follow for Spencer, as the stream of victims gave way to a stream of relatives. Like the young woman police officer whose house he and others would drop in “for a pot of tea” on their break from the beat and who turned up, hoping that her own son had been registered safe. He had died, too, and Spencer, who had been gathering names for hours by then, knew it. “From what I could see in front of me, it was clear the boy was missing,” he says. “She knew it. I knew it. I wanted to get hold of her and give her a hug. But that was not done in those days, you know.”

The power of such recollections were to be found everywhere you turned in Bradford this week. “It still shakes me up when I think about it,” says Paul Hunter, standing at the stadium memorial on Thursday. He will be at Valley Parade for the Cup match against Reading with his son on Saturday. “I was 24 that day and I was there with my brother who was 19. It’s something that never entirely leaves you.”

Both Spencer, now 66, who retired in 2003 and Preston were told they must attend counselling after their experience. They reported to what they remember as something like a doctor’s surgery up in Leeds, where from 10.15am on a summer’s day in 1985, police officers were called in, one by one to see a certain “Dr Duckworth”. Neither Preston nor Spencer went back after that first counselling session. “It probably helped that I was kept busy by my work for the inquiry,” Preston says. “There was something to get on with. It was a harder world back then.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments