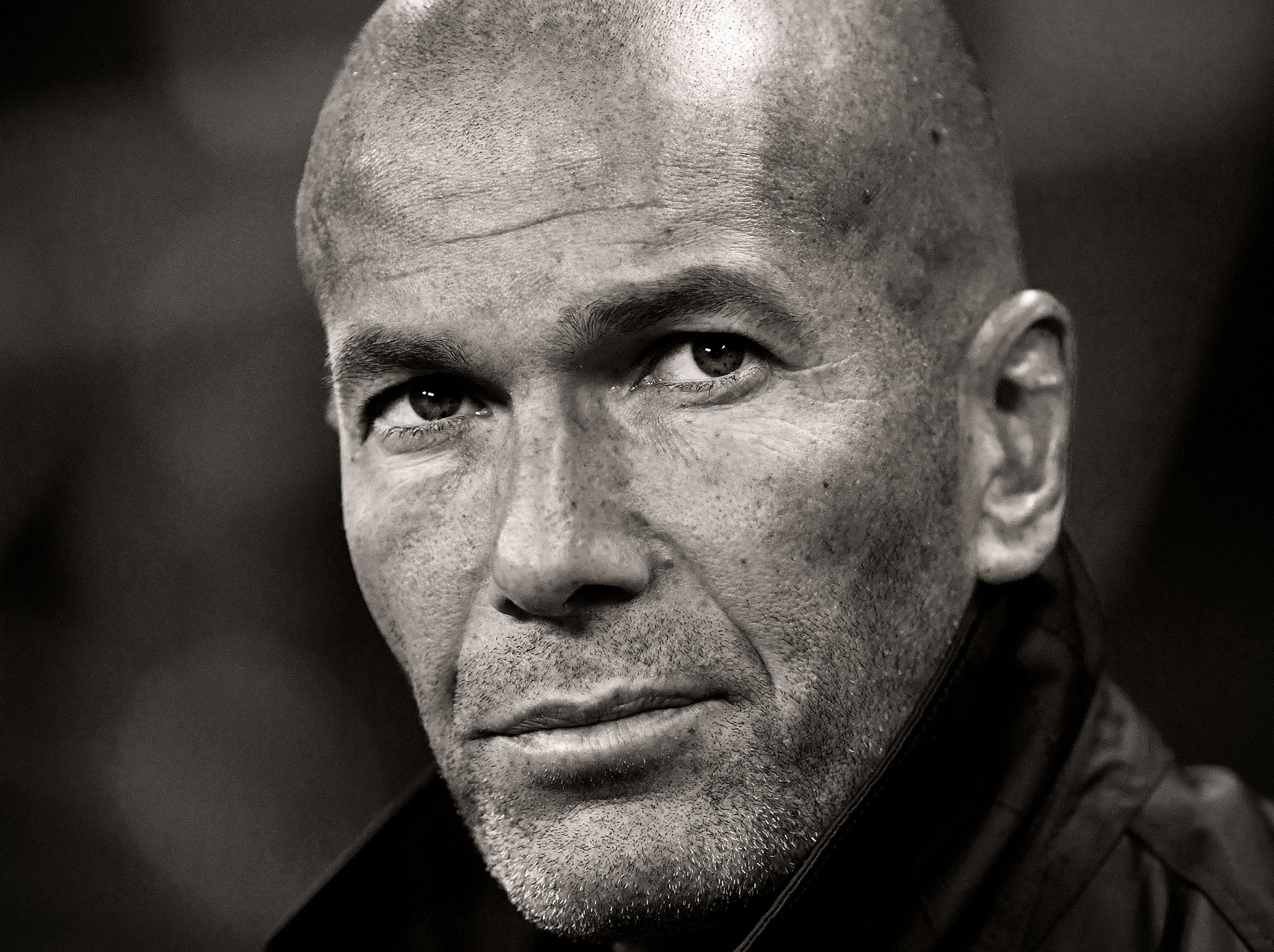

Zinedine Zidane beware - the Champions League often serves as a solitary jewel in a middling managerial record

It is time for the Real Madrid manager to prove that he is a managerial great who forges his own destiny, rather than just a figurehead in the right place at the right time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just as the European Cup has two handles as a trophy, it also has two sides as a symbol. The hugely prestigious piece of silverware is most commonly seen as a unique crowning glory in a great manager’s club career, that truly immortal feat that lifts them onto another level in the game’s history, but an under-appreciated reality is it has just as often served as a solitary jewel in some very middling records.

You only have to look at some of the names who have won it, and look at how little they won in the rest of their career.

Lifting the trophy might have involved a lot of long nights of the soul and thereby been a holy grail for genuine greats like Sir Matt Busby, Sir Alex Ferguson, Giovanni Trapattoni, Rinus Michels and Helenio Herrera, but it also undeniably fell so much more easily to otherwise overlooked names like Luis Carniglia, Dettmar Cramer, Stefan Kovacs, Tony Barton and Roberto Di Matteo.

This is one of the inherent contradictions to such an illustrious prize.

It is also the big challenge now for Zinedine Zidane, the extra edge to his Real Madrid anguish. He must prove he is a managerial great who forges his own destiny rather than just a figurehead who was just fated to be in the right place at the right time. Even the fact he has two medals as manager isn’t such a mitigating factor, given that Carniglia, Kovacs and Cramer did too, and they don’t tend to appear in many appraisals of the game’s legends.

This is of course as much about the manifold contradictions and characteristics of managing a big club. It's about the natural cycles they go through. While so many of those greats have had to endure those long nights of the soul because they have been responsible for properly building up something new, or have sought to impose a grander philosophical idea on a team that means they come to represent something bigger than just winning, that isn’t always the case.

One consequence of that is those same big clubs, and often those same squads, next just need someone to facilitate them; to oversee them; to keep things ticking. They need something more simplistic after the hard work has been done.

This was first most visibly the case when Kovacs took over Ajax in 1971 after Michels had changed the entire structure and standpoint of the club, and then when Cramer took over the great Bayern side of 1973-76 after they had properly come together to win the European Cup in 1974.

As Uli Hesse puts it of that Bayern in his history of German football, Tor!, “it was secretly whispered that any fool would have lifted silverware with a squad that included [Sepp] Maier, [Franz] Beckenbauer and [Gerd] Muller". Beckenbauer himself is quoted as saying that by that point - after they had won three successive leagues and a European Cup - “the team didn’t need a manager, it needed a psychologist”.

In other words, there was so much positive already in place that they only needed nuance rather than navigation, occasional steering rather than full structural direction. This is what Kovacs and Cramer did, winning two European Cups each with Ajax 1972, 1973 and Bayern 1975, 1976 respectively.

The nature of a knock-out competition like the Champions League’s latter stages only further facilitates this itself, given that a mere three good games and a large dose of luck can help a manager and his side win the greatest of prizes in the worst of seasons. Barton’s 1982 Aston Villa, Jupp Heynckes’ 1998 Real Madrid, Rafa Benitez’s 2005 Liverpool and Di Matteo’s 2012 Chelsea are the ultimate examples.

It has been difficult over the last few years not to ascribe some of this to Luis Enrique and Zidane.

If it sounds harsh, consider some of the hard details.

Both came into jobs with two of the greatest and widest squads ever put together. More importantly, those squads had standards and other values imbued into them by previous figures and grander projections of the clubs, and had already got to a point where they were achieving an abnormally high return of points in the league and regular appearances in the Champions League semi-finals regardless of who was in charge.

When that’s your position, and you're that advanced, it doesn’t take too much to go the distance. It’s just a few minor touches; even steady decisions rather than strong ones.

That is not to diminish their work, given those minor decisions still require intelligence, good judgement and insight but the bald truth is that is just not the same as building a side up from deeper; of also imbuing them with something deeper and really changing how they play.

One big indication is that when you talk to anyone at Real, they don't really go into detail about what Zidane actually does.

They talk of the "atmosphere" he creates, the occasional tactical tweaks, and the value of his great player’s experience in little moments. That is still the description of someone that is just overseeing this side; facilitating it.

They don’t talk of hard structures, and the absence of that becomes apparent in sudden faultlines appearing in the side when form inevitably begins to dip, of inexplicable big gaps in how they play when they're not playing well.

That is when you see the difference between the proper managerial force and the facilitator. Gaps become apparent in a team’s structure, players stop working in the same way. In other words, the short-term effects that were once what was required wear off. It's similarly difficult not to think we saw so much of this in that dismal Real Madrid defeat to Spurs - just as we eventually saw it with Barton’s Villa, and Di Matteo’s Chelsea.

The big question is whether Real president Florentino Perez is going to do what many have long suspecting him of wanting to, and look to someone else; whether he already thinks this Real require someone else.

To prevent that, Zidane is going to have to show something different. He is going to have to get right under this team and into them, rather than just oversee them.

He is going to have to show another side.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments