Booing, controversy and anti-Juventus songs: Maradona returns to Napoli to be legitimised as the city's favourite son

The Argentine came back to the city to be made an honorary citizen 33 years to the day he was unveiled

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Thirty three years to the day since he was unveiled as the world's most expensive player, Diego Maradona was back in Naples on Wednesday night to be made an honorary citizen.

In 1984, he was introduced to around 60,000 fans, each paying 1,000 lire, at Stadio San Paolo following his record-breaking move from Barcelona. It was a moment that marked the start of one of the game's truly great love affairs.

This time, around a quarter of that number filed into Piazza del Plebiscito in the heart of Naples' historic centre to witness the latest emotional encore from the city's favourite adopted son. It was supposed to be a night of unadulterated joy and celebration.

This being Maradona, however, the trip was not without controversy. He flew in from the Confederations Cup in Russia, where allegations - which he denied - had surfaced that he had sexually assaulted a journalist.

There was also fall-out over the 180,000 euros Maradona was supposedly paid to attend the event in Naples. Local paper Il Mattino reported the story vigorously. Had this dampened local excitement? Was it the reason why only half the expected number of fans turned up on the night?

There was even the odd dissenting voice among the 1986-87 Scudetto-winning team, whose achievement three decades ago was jointly being commemorated. Salvatore Bagni, that wily ex-Italy midfielder, suggested the entire squad ought to be made honorary citizens. Alessandro Benica, the libero from the side, agreed - but added that, in order to ensure Maradona got the extra credit his genius deserved, perhaps the San Paolo could be renamed in his honour.

Maradona has never needed to appear in person for the ties that bind him to this city to be apparent. There's the giant mural of him painted on the end of a housing block on the eastern outskirts of the city, the words 'Living God' scrawled across the bottom. There's the shrine to him at Bar Nilo, on Via San Biagio dei Librai, a short walk from where the citizenship ceremony took place. In it, a reliquary houses a lock of his hair. Another holds tears that, it's claimed, date from 1991, the year he played his last game in Napoli colours.

Media coverage was as broad and intense as you'd expect. The sports papers devoted dozens of pages to it. Regional TV station Canale 21 renamed Wednesday 'Maradona Day', carrying a special logo in the top corner of their screen. Given such fervour, it's little wonder you're still more likely to see 'Maradona 10' shirts on the rails of the city's street vendors than those of modern-day Napoli heroes Dries Mertens or Marek Hamsik (now just two goals behind Maradona in the club's all-time scoring charts).

When the ceremony started at 9.45pm, a succession of local musicians took to the stage. They performed and paid personal homage to the man that inspired Napoli to two Serie A titles, an Italian Cup and a Uefa Cup. There was an appearance by a Maradona 'super fan'. He brandished three Maradona shirts: one from 1973 when a 13-year-old Maradona played for local junior side 'Los Cebollitos ('The Little Onions') in Buenos Aires, the second from the 1982 World Cup and the third from Argentina's last-16 win over Uruguay in 1986.

Yet the tifosi were there only to see 'El Pibe d'Oro', and grew restless. One band was booed simply for not being Maradona. The compere tried to appease the crowd: "Don't worry, Diego's here - you'll see him soon."

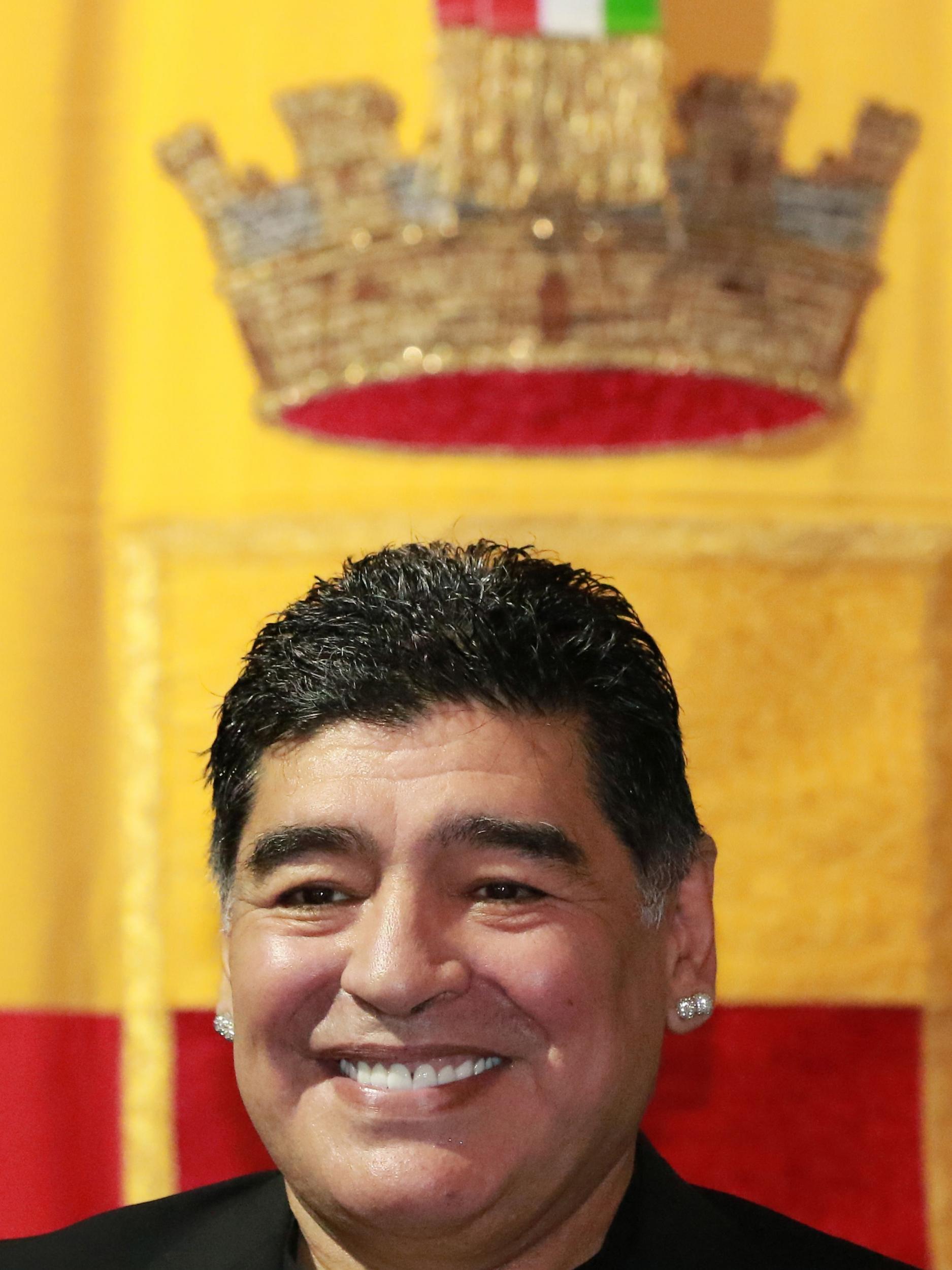

And there he was. Shortly after 10.30pm, he made his entrance. Short, squat, dressed in a black shirt and black suit, he strode about the stage, waving and milking the applause, his grinning face projected on to the big screen behind him.

A rendition of the 'O mamma, mamma, mamma!' Maradona song broke out. Maradona joined in with the anti-Juventus chants. The PA system played Opus' 'Live is Life', a tribute to that YouTube video.

When the noise died down he made his speech. He told the fans nobody had ever loved him like they had. He said he would take up with Fifa president Gianni Infantino the issue of "the racism and discrimination" that Neapolitans face. The address lasted 10 minutes. The loudest cheer came when he declared "chi ama non dimentica" - he who loves doesn't forget.

Team-mates from the 1986-87 squad were called up one by one. Bruno Giordano and Andrea Carnevale - the other two members of the famous Ma-Gi-Ca forward line - were among them. Former Italy defender Ciro Ferrara, who left Napoli for Juventus in 1994, was roundly jeered; even Maradona, beckoning to the crowd, was powerless to stop that. He was so much smaller than everyone else. Hugging him, a couple of team-mates picked him up fondly.

With proceedings coning to an end, there was still time for a football to be thrown on stage. You knew what everyone hoped would be coming next - but Maradona wasn't playing ball. No doubt weary of being a performing seal for half a century, there were no tricks, flicks and kick-ups this time: instead he booted it straight back into the crowd (yes, left foot).

And that was it. Leaving the arena, Maradona half-turned for one final sing-song before vanishing from view. Five minutes later, he was being whisked out of the square by a high-speed police calvacade, chased into the night by fans in shorts and flip flops too young to have ever seen him play.

In Naples, you sense, this will always be the way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments