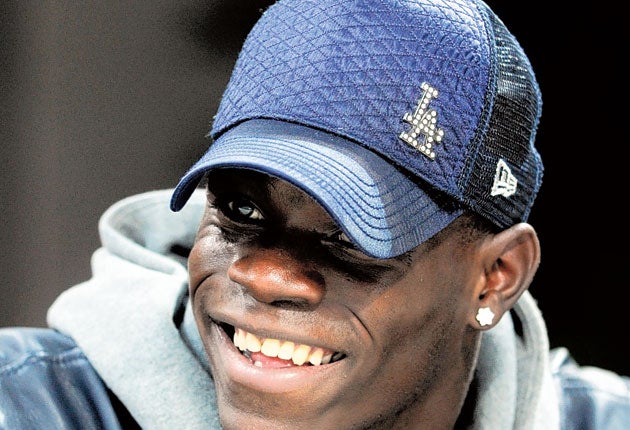

Balotelli: The star playing a losing game against racism

Manchester City's striker may be the future of the Italian football team, but he faces a familiar scourge back home.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Mario Balotelli appeared on the front of the Italian Vanity Fair in May this year wearing only the Italian flag, draped across his shoulders, he looked every bit the image of a modern multiracial nation. Italy, the picture told us, was embracing a rising force of football; young, handsome, gifted, black.

But the real story of one of Europe's most controversial footballers, who left the Milanese club Internazionale in August and joined Manchester City, is neither as glossy, nor as simple, as that image would have us believe. Born Mario Barwuah to Ghanaian immigrants in Palermo in 1990, Balotelli has come to represent the complex picture of race in Italy all too accurately.

On Wednesday Italy's national football team played Romania in a friendly held in Austria. Balotelli was abused by his own team's supporters. A banner was held up saying: "No to a multiracial Italian team." Italian police blamed the racism on a right-wing group called UltrasItaly and insisted that such abuse would not occur inside an Italian stadium. It was less than convincing – Balotelli was regularly subjected to abuse while playing in Italy last season, when the banners held up by followers of rival club Juventus read: "A negro cannot be Italian."

Mario's biological parents moved to Brescia, in the north of the country, while he was a toddler and he was handed over to the middle-class Balotellis to be fostered. He was scouted by the current Spanish champions Barcelona as a teenager, but joined Inter Milan, making his debut at 17. He started well, but before long a provocative, petulant streak emerged that has, in Italy at least, complicated the racism debate ever since.

Most Italians will tell you: Balotelli would be abused whatever colour he was. When he was abused by Juventus fans in Turin last season, the club was forced to close its ground and play before empty stands. But even AC Milan's black midfielder Clarence Seedorf suggested the abuse could be more a reflection of Balotelli's personality than his skin colour.

Balotelli has a reputation. One story that circulated in Manchester after he arrived this summer was that, after he crashed his custom-built Audi R8, police found him at the scene with £5,000 in cash hanging out of his back pocket. When asked why he had so much money, he replied: "Because I'm rich." It was funny in Manchester, especially among supporters of City, the richest club in the Premier League, but in Italy his brashness was hard to take. Balotelli was king of bling in a country that has struggled to absorb black culture, let alone bling culture.

His ability to upset everyone, even those who are, or would like to be, on his side was picked up in the recent Vanity Fair interview, when he admitted to having been spoilt with too much patience by his foster parents, and said that "his head sometimes leads him astray on the football field". Those who have seen him sit down and sulk mid-match after something does not go his way will vouch for that.

Balotelli knows his attitude adds to the problem. "It's because I always want to be the centre of attention and sometimes others don't like it," he said. He managed to be the centre of attention last April when, at the end of an epic Champions League semi-final against Barcelona, he threw his Inter Milan shirt down on the pitch as a protest at what he perceived as a lack of enthusiasm from the team's supporters. That action prompted his team-mates and manager, Jose Mourinho, to share the opinion of those in the stands.

But in this troubled, talented man there nonetheless lies an uncomfortable truth about race in Italy. Last Wednesday he received the same sort of abuse suffered by England's black internationals 30 years ago.

Back then Britain's considerably larger immigrant population was at a similar stage of integration. But in Italy, as with some other southern European countries, a distinct black, African, migrant underclass is characterised by street vendors. The perception is far from that of the Windrush generation, many of whom were put to work in public-service jobs. And when the first black footballers arrived in the English game, they did so as a group, with an identity, albeit couched in comfortable stereotypes – hence the "Three Degrees" of Cyrille Regis, Laurie Cunningham and Brendan Batson at West Bromwich Albion in the 1980s (signed by Ron Atkinson).

But Balotelli stands almost alone. By his own standards, his condemnation of events in Austria was admirably eloquent. "What happened is racism but it is also the stupidity of a few people," he said, adding that it would have been an over-reaction to protest by leaving the field for "a few idiots". "I'm on my own, I can't do anything," he said. "Everyone has to do something against racism. I'm not the one who can make these people change."

Perhaps he is right. But the 20-year-old is growing into his role as Italy's race flag-bearer, slowly, with charity work and occasional moments of humility. Asked about his beliefs, in the Vanity Fair interview he replied: "I would never pray to win a title; it makes no sense. I've never understood those who pray before a match. But I give thanks for what I have received. The other day I met some child soldiers. They told me their story and while I listened, I thought: It could easily be me in their shoes."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments