Declaration of war... but the show goes on

It took a while for the county game to come to terms with the conflict in the summer of 1914 – but then W G Grace stepped in

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cricket continued after Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914. It was sensitive enough to avoid pretending that nothing had happened. "War being declared on the Tuesday, the Canterbury Week was, of course, shorn of most of its social functions," said Wisden Cricketers' Almanack the following year in its report of the match between Kent and Sussex.

Canterbury Week was the acme of cricketing festivals. It had to proceed. But the season meandered on. Nine days after the announcement of hostilities, Kent visited Edgbaston to play Warwickshire. On the first day 30 wickets fell, three of them in one over from Percy Jeeves.

The second of these was the dismissal of Colin Blythe, bowled by Jeeves for a duck. Blythe and Jeeves were to be linked forever by more than their names on a scorecard. They would both be killed in the war, among the 289 men who had played first-class cricket to die in uniform.

A century on, they have become – for different reasons – the two most renowned of the casualties. Wisden's obituary of Blythe said: "The loss is the most serious cricket has sustained during the war." He was one of the greatest of all England's left-arm spinners, taking 2,506 first-class wickets at 16.81 apiece, 100 of them in Test matches at 18.63.

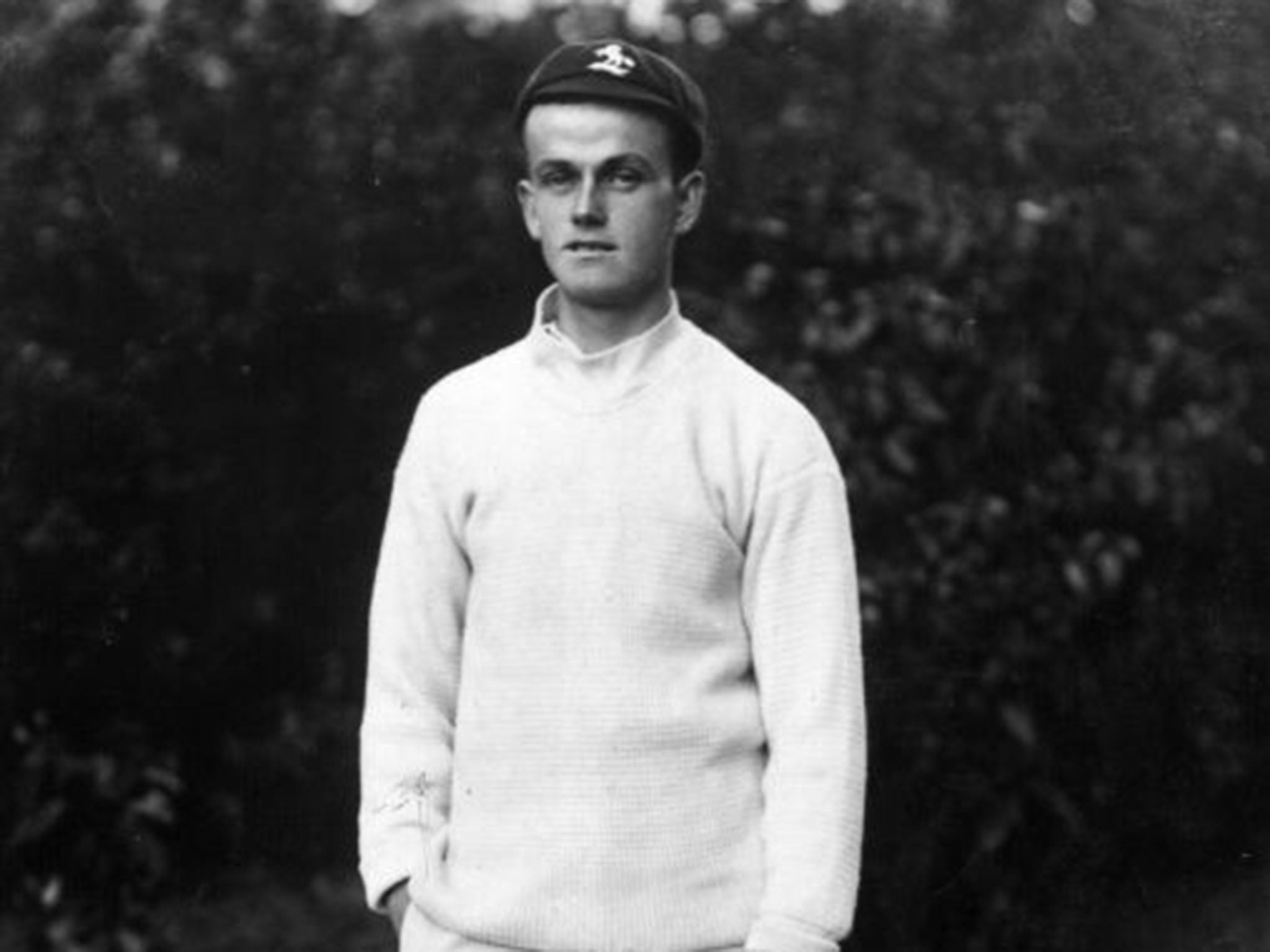

At the time, the death of Jeeves, a promising Warwickshire all-rounder barely at the start of his career, was just another tragedy in an interminable list. His name has become immortal because it was used by PG Wodehouse for his fictional manservant to Bertie Wooster, the inimitable Jeeves.

In those early weeks of August, while the British Expeditionary Force were suffering enormous casualties, the country was in a state of confusion which cricket reflected. The Oval was requisitioned, which meant the benefit match of the great Jack Hobbs was moved to Lord's.

MCC issued a statement saying they felt "no good purpose can be served at the present moment by cancelling matches unless the services of those engaged in cricket who have military training can in any way be utilised in the country's service."

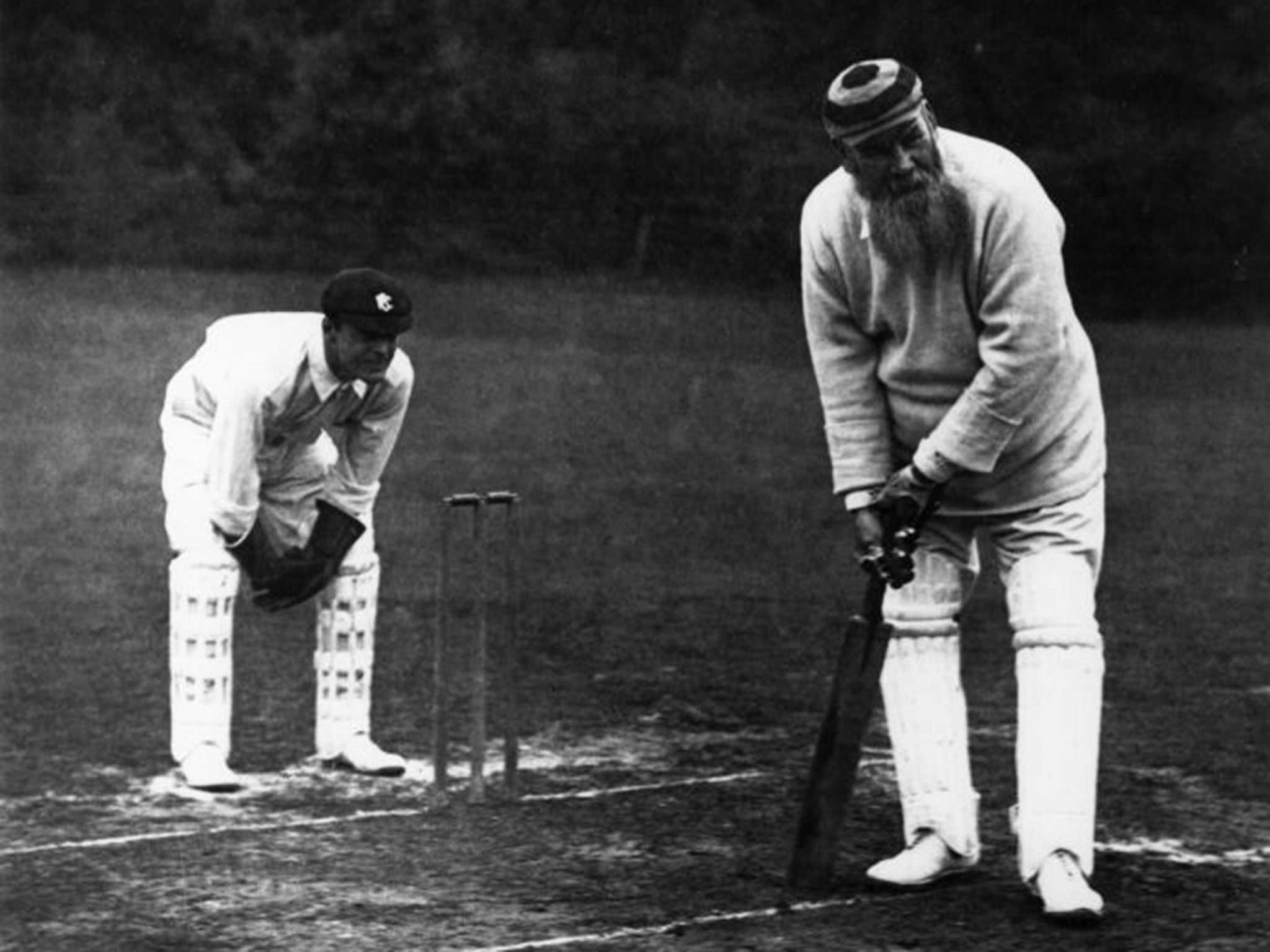

Blythe and Jeeves cannot have known the fate that awaited them that day at Edgbaston on 13 August 1914. They were to meet yet one more time on the cricket field, at Gravesend two weeks later, when still the season lingered and Kent again prevailed. On the same day, 27 August, in The Sportsman newspaper, W G Grace issued his command to sportsmen of England to enlist.

"The time has arrived when the county cricket season should be closed," he wrote. "It is not fitting at a time like this that able-bodied men should be playing day after day, and pleasure-seekers look on. There are so many who are young and able, and still hanging back." Cricket is magnificent at remembering the past, and the intertwined stories of Blythe and Jeeves serve to remind of what the game and the world lost. The cricketers who died are recalled in the general and in the particular. Wisden On The Great War – The Lives of Cricket's Fallen 1914-1918, edited by Andrew Renshaw, is much more than an anthology of obituaries from the original Almanacks, though it is that as well. It records the deaths of 1,800 men with cricketing connections and tells how the war affected the game.

The part of the man immortalised by PG Wodehouse was chronicled in resonant detail last year by Brian Halford in his The Real Jeeves, which was not quite given its due at the time but still has a grim pertinence.

Jeeves was both typical and untypical. He came to first-class cricket late; born in Dewsbury, he moved to Goole and became a professional at Hawes in Wensleydale, where he was spotted by the Warwickshire secretary, who was on holiday at the time. Jeeves qualified to play for the county in 1913 and had a spectacular couple of seasons as a fast-medium bowler and attacking middle-order batsman. Then, like almost all the rest, he joined up.

The war which took him and his colleagues away from their lovely existences as professional cricketers in the game's golden age and changed everything forever was a surreal presence at first.

A few matches were cancelled, most went ahead. But they were played in peculiar circumstances. For instance, on the second morning of Warwickshire's last match, against the champions, Surrey, their fast bowler Colin Langley left to join his regiment.

Off went both Blythe and Jeeves to the colours, part of the legions of volunteers who flocked for training, including 210 of the 278 men who played first-class cricket that summer. Jeeves joined the Birmingham Pals. He was killed on the Somme in July 1916. Blythe, at 36 playing regimental cricket, volunteered for the front after his 19-year-old brother was killed on the Somme and was himself killed by shrapnel at Passchendaele in 1917.

'Wisden On The Great War', edited by Andrew Renshaw (John Wisden & Co, £40); 'The Real Jeeves', by Brian Halford (Pitch, £16.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments