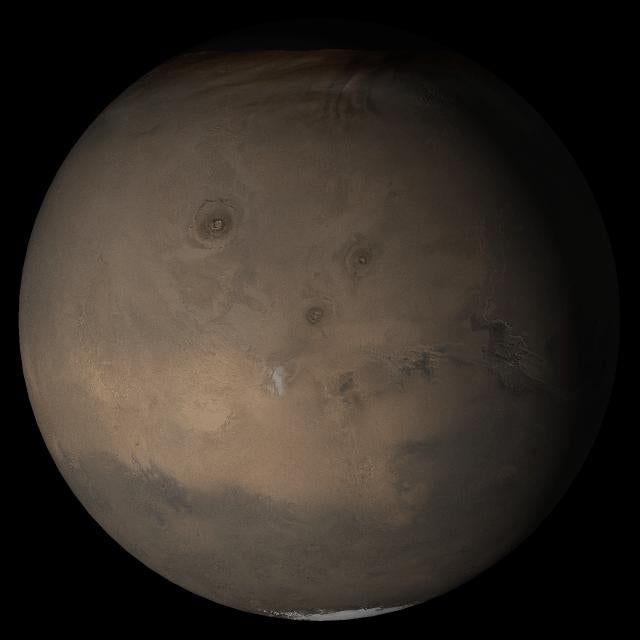

Nasa Insight mission proves Mars’s crust is thicker than scientists thought

Although Nasa’s Insight lander is nearing the end of its mission, its still providing scientists all new glimpses at the interior of the Red Planet

The outermost layer of Mars is denser and more uniform than scientists once thought.

That’s according to new findings from Nasa’s Insight mission that are published Thursday in the journal Science.

A Martian geology mission, Nasa’s Insight lander has been listening to Marsquakes since 2018, using information contained in the speed of the waves propagating through the Red Planet to gain insights into its deep structure. But the new findings published Thursday provide a new understanding of the structure of the planet’s crust, from the surface down to between 8 and 48 miles depth, all thanks to the Insight capturing the vibrations generated by a meteor strike in December 2021.

“Until now, our knowledge of the Martian crust has been based on only a single point measurement under the InSight lander,” ETH Zurich Institute of Geophysics senior geophysicist and lead scientist behind the study, Doyeon Kim, said in a statement.

Understanding Mars’s crust can help scientists better understand how it formed and evolved over time.

The December meteor strike created what are known as surface waves, seismic vibrations that propagate along a planet’s surface rather than from the source of a quake deep inside the planet. That Insight recorded surface waves alone is a milestone.

“This is the first-time seismic surface waves have been observed on a planet other than Earth,” Dr Kim said. “Not even the Apollo missions to the Moon managed it.”

Surface waves propagate at different speeds depending on the density of the material they travel through, and the surface waves reaching Insight from the meteorite impact location about 3,500 miles away indicated that the Martian crust is denser and more uniform in structure than previously thought. That’s due in part to the fact that the measurements of the crust directly beneath Insight are not as dense as it appears is typical for the planet.

“The crustal structure beneath InSight’s landing site may have been formed in a unique way, perhaps when material was ejected during a large meteoritic impact more than three billion years ago,” Dr Kim said. “That would mean the structure of the crust under the lander is probably not representative of the general structure of the Martian crust.”

The findings challenge the leading theory for explaining what is called the Mars dichotomy, the fact that the northern hemisphere consists largely of volcanic lowlands, while the Southern Hemisphere is a meteorite cratered plateau. It had been theorized that the crust beneath the two hemispheres was dramatically different material, but the new study suggests that’s not the case.

“As things stand, we don’t yet have a generally accepted explanation for the dichotomy because we’ve never been able to see the planet’s deep structure,” ETH Zurich Professor of Seismology and Geodynamics Domenico Giardini said in a statement. “But now we’re beginning to uncover this.”

The new findings come just in time, as Nasa’s Insight mission is likely to end soon, as the lander is losing power due to dust accumulating on its solar panels. But in May, the lander provided one last gift: it recorded the largest Marsquake ever observed, a magnitude 5 temblor, which produced further surface waves and will allow Dr Kim and other researchers to make more discoveries about the structure of Mars even after Insight shuts down.

“It’s crazy. We’d been waiting for so long for these waves, and now, just months after the meteorite impacts, we observed this big quake that produced extremely rich surface waves,” Dr Kim said. “These allow us to see even deeper into the crust, to a depth of about 90 kilometers.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies