Yasmin Alibhai-Brown: Experience is not the same as expertise

I wish Russell Brand well and respect his resolve, but he is neither a saviour nor a reliable authority

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

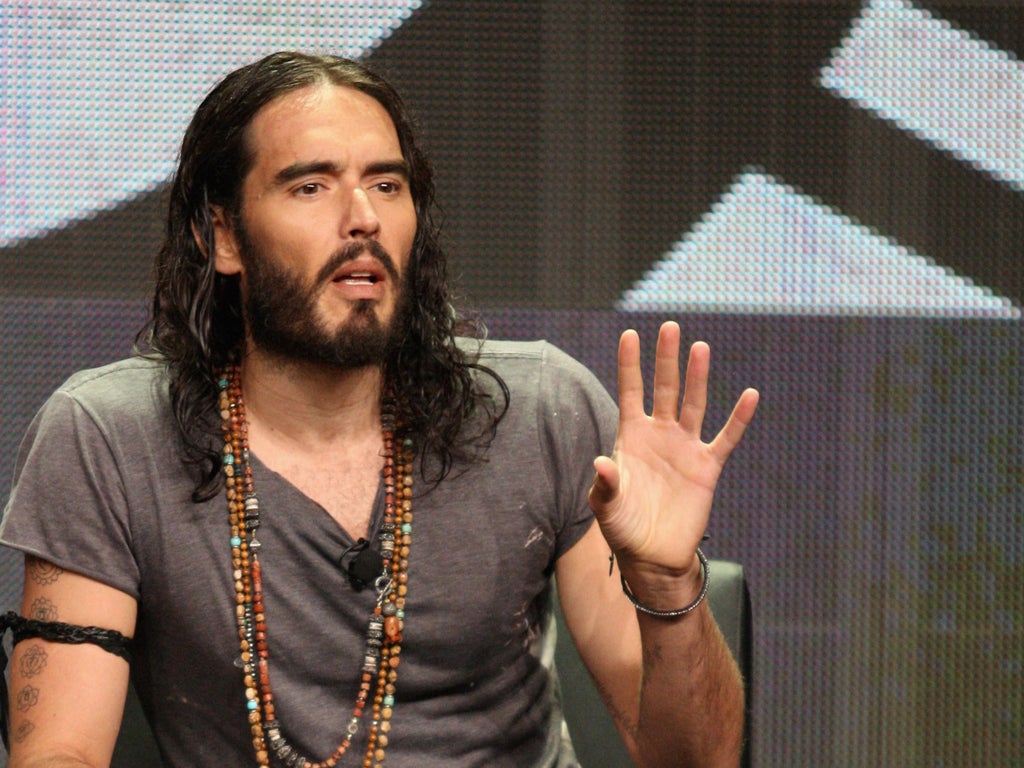

Your support makes all the difference.Russell Brand, with his Jesus hair and beard, manic eyes, hyperactive brain and sublime verbal dexterity, is no doubt special. But not so special that he can casually jettison the wisdom and views of parliamentarians and most specialists on the nation's drug policies. After appearing this April before a Home Office select committee, Brand informed the nation that politicians didn't know what they were doing when it came to drug addiction. But Brand himself did, having been an addict once.

After many other incarnations, Brand now wears the mantle of reformed sinner, and he harvests all he can from that period in his life when he was lost in a drug fug. After his parents' divorce, he was taken to prostitutes by his dad so that father and son could bond. He was sexually abused by a neighbour, developed an eating disorder, and by his twenties was a heroin addict. He's been clean for a decade, no mean achievement in one so young and wild and famous. I really do wish him well and respect his resolve.

But he is no saviour, not a reliable authority. He once candidly admitted that he was "a highly defective individual, prone to self-centredness, self-pity and self-destructive, grandiose behaviour". Yet now he is out there fronting a BBC programme about his semi-conscious phase, persistent cravings for heroin and the only solution for substance dependents – no methadone, total abstinence.

We need to ask if previously troubled, then redeemed people are the most dependable of experts. Expertise is not a revealed religion. It comes out of learning, analysis, experimentation, and research material, and it needs to be detached from emotional ups and downs. Celebs can help to de-stigmatise or publicise problems. Stephen Fry, for example, has done that brilliantly for bipolar disorder. They can lend their names and biographies to charities needing funds. Cancer charities depend on high-profile patients to advertise the cause, both for health messages and donations. If laddish drunks like George Best and Oliver Reed had been "cured" through some miraculous rehab technique, they could have made themselves socially useful by letting other compulsives in on the secret. But troubled and reformed individuals believing they can determine or drive policy is daft and dangerous.

I recently met a woman who has been a career mistress and is writing a book on divorce and the law. She thinks she knows better than lawyers and judges because after bedding unhappily married and divorced blokes, she knows the law's an ass and what needs to be done to make it "fit for purpose". Well, why not? Her agent says someone needs to make the law "sexy".

Since 9/11, a number of Muslims have become advisers to governments, not because they have studied extremism but because they were once that way inclined. Their experiences undeniably illuminate an otherwise shadowy world and redress shallow and ignorant assumptions made about Islam and its believers.

A new book, Radical, by Maajid Nawaz, is one of the most mesmeric I have ever read on such a transformation. The British-born author explains why he turned Islamicist. He writes about his time in an Egyptian prison under Mubarak when he was adopted as an Amnesty prisoner of conscience and his subsequent democratic awakening. He is the co-founder of Quilliam, a progressive Muslim think-tank. The other founder, Ed Husain, wrote a bestseller about his journey into radicalism and back out again into enlightenment. These educated, rightly esteemed men now advise top people in the UK and the US. But there is still this niggle that "turn'd radicals" get more serious attention than do Muslims and non-Muslims producing erudite papers and books which contain no confessional U-turns. You can find many such in a new quarterly magazine Critical Muslim, co-edited by the polymath Ziauddin Sardar.

The most famous case of victimisation or self-delusion leading to sainthood is that of the clever and beautiful Aayan Ali Hirsi, the Somali-born apostate who has been living under a death threat since 2004, when she made a film about women suffering under Islam, with Dutch director Theo van Gogh. He was assassinated by demonic fanatics. Her inner panic over so long must be unimaginable. But her persecution has made her into a fuming neocon babe whom hard-line Republicans listen to seriously on foreign affairs and on the shaping of internal policies on Muslims. Scary, that.

To make a real difference to the world, terrible occurrences have to be processed and tested. Ruby Wax, for example, has gone back to university, to study depression, an affliction that often disables her. Her recent TV programmes on the subject had both depth and objectivity as a result. American writer Jessica Stern has turned her own pain into a noble vocation. A nice Boston girl, raped by a neighbour when she was 15, she now finds, talks to and writes about men who are violent and extremist. Her book, Terror in the Name of God, is compelling because the personal never overwrites the political.

That is the problem with the Brand model. As Sardar once wrote: "Just because you've been an inmate in a mental hospital, doesn't mean you are an expert in clinical psychology."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments