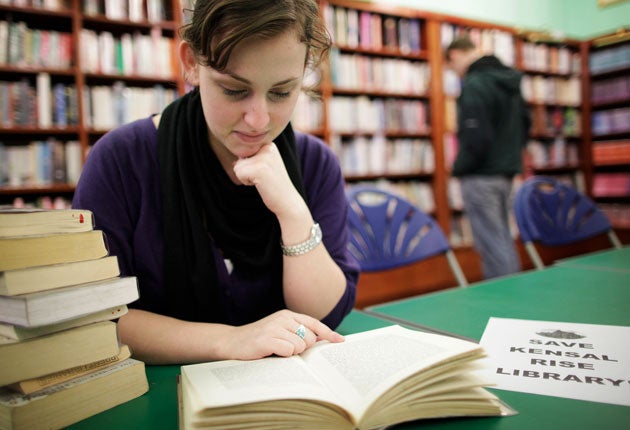

Tim Lott: The local library, a beacon of civilisation

They are a symbol of what we as a country stand for, and nationwide groups are forming to fight the threat of closure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This is not a story about the campaign to save at least 600 libraries nationally under threat – the threatened closure of which attracted so much attention last week – but a story of personal conversion. I admit, when it was announced that my local library, Kensal Rise in north London, was one of six libraries to be closed in my borough, following massive cuts in its central government grant, that my response was one of mute resignation.

I've never been much of a protester: my greengrocer father imbued me with the residual working-class fatalism of council estates and the poorer suburbs. It's a world view which assumes the powerful always get their way in the end, so dissent is futile – or that someone else, somewhere else, will fix it.

This ignoble prejudice apart, Brent Council seemed to have a strong case. The cuts had to come somewhere. If we, a prosperous middle-class area, didn't take the cuts on the chin, then poorer people would. Not enough people used the library – according to the council, it cost £4 per visit. Libraries were becoming things of the past in a world of information technology, ebooks and cheap second- hand paperbacks on Amazon. And we had another good library about a mile and half away that would extend its hours if our library shut.

However, a close friend and close neighbour wasn't prepared to take it on the chin. At the end of last year, he made an impassioned speech at the first council executive meeting dealing with the library closures, while I slumped in front of the telly with a glass of plonk.

Ashamed at my initial apathy, I attended the first protest meeting, held at the 110-year-old library, a few weeks later. The library was full to the rafters with concerned local residents. It emerged during this meeting that while Brent was set to save £1m by closing six libraries, the council was opening a new civic centre vanity project costing £100m, which would include a sumptuous new library complex – lovely, but far too far away for most of Brent's residents to reach easily. A committee was to be set up to fight the closure. But the council members who had attended the meeting were insistent – the council was broke. It was like mugging someone with no money.

At the first committee meeting, a week later, lawyers, wine dealers, journalists, writers, administrators, interior designers – the middle-class protest movement in full flow – flocked in. I don't know if they frightened Brent Council, but they scared the hell out of me – articulate, clever, determined, impassioned, connected, efficient. I began to believe that the campaign could work.

But there were practical and moral difficulties. We didn't have the time to put a Big Society, locally run alternative in place. The library was in the ward of the councillor in charge of the closures– it would look like special pleading if it were saved and others not. And weren't we just nimbys safeguarding middle-class interests at the price of less privileged members of Brent society?

Delivering Save Kensal Library leaflets from door to door, reality dawned on me. The vast majority of the houses did not have a Farrow & Ball front door and acid-etched number in the fanlight. Plastic, steel or flaking doors led mostly to small flats. Front yards were unkempt; the furniture glimpsed through windows cheap and stained.

Amid the rising property prices, new delis and gastro pubs, there was social housing and relative poverty. Many people here could not afford to buy books, let alone computers like those provided free in the library.

I started to contemplate my own life growing up as a child without any books in the house – other than library books. And how I filled the long hours with nothing to do by walking the few hundred yards – about the same distance as my current library – to spend long afternoons reading first the Moomintroll books and Tolkien, and later Dostoevsky and Golding. For someone living in an otherwise literature-free zone, it was my only chance as a child to access culture, other then the television, and it was free and readily available. Without the library, I would never have become a novelist or written any books at all. It was a lifeline.

And the library remains a lifeline for many of the families in my area – not all white, not all middle class, not all well educated, by any means. It is a beacon of civilisation, a mark of what we as a country stand for. For we remain, per capita, the most literate country in the world – we produce and read more newspapers and books per head than any other nation. And it's vital we keep it that way, as economic inequalities multiply, and the world divides into information rich and information poor.

By now I have no doubts whatsoever that we should fight tooth and nail for survival of this library – and everyone throughout the country whose own library is threatened should do the same. And I am convinced we, and many others, can win. Hundreds of people have signed up for this local campaign, and the number grows every day. We are strong and we are determined and we are not about to take this lying down.

But as I say, this isn't a story about one local library – or the 599 others at risk. Whatever happens, I have come out of the experience radicalised and deeply impressed by the righteous power of what I once would have lazily dismissed as bourgeois do-gooders. Community action is a liberating and powerful experience. David Cameron has talked of his desire to encourage this kind of activism in local communities – but he may not realise just what a genie he is letting out of what kind of bottle.

Local groups like ours are arming themselves with resources and information, empowering themselves about the policies that ultimately central government, under Cameron, is instituting. The Big Society is not all cuddly: it can be dangerous, especially for a government set on undermining society by scuppering the NHS, or education, or libraries, or anything else we hold dear.

Cameron, and all the other agencies of power, had better beware, if this becomes a trend up and down this benighted and exploited nation. The motto of the Big Society should not be "small government", code for closing down essential services, but: "We're as mad as hell and we're not going to take it any more."

Zadie Smith reads from her new book and defends libraries on 29 March at The Paradise, Kensal Green, London NW10

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments