Paul Vallely: A tax on bargain booze is a cheap trick

Raising the price of cheap alcohol fails to address the most alarming rise in problem drinking – among the middle classes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The judge peered down at the incorrigible character in the dock before him. It was his 42nd conviction for being drunk and disorderly but the prisoner pleaded for leniency with all the fluency of his new-born sobriety. The judge softened and promised not to jail him, again, so long as he kept to his promise to give up drink completely. I will, I will, said the old tramp. "Good," said the judge. "But I mean completely. And that means not even the teeny-weeniest sherry before lunch."

Such was the tale an ancient court reporter told me – in the pub – in the days of my journalistic apprenticeship. Even then, the business of class was hopelessly entangled with that of alcohol in the British mind. So it was again last week with the Government's plan to bring in a minimum price of 40p per unit of alcohol in an attempt to stamp out binge drinking.

"Too many people think it's a great night out to get really drunk and have a fight in our streets," the Home Secretary told television viewers. The crime and violence caused by binge drinking, the Prime Minister added, "drains resources in our hospitals, generates mayhem on our streets and spreads fear in our communities".

So, while the price of a magnum of Bullingdon Bollinger will remain unchanged, these staggering, vomiting lager-oiks, and their teetering, white-stilettoed girlfriends, are to have the price of their supermarket-purchased cheap booze nearly doubled in price. It's for their own good, you see.

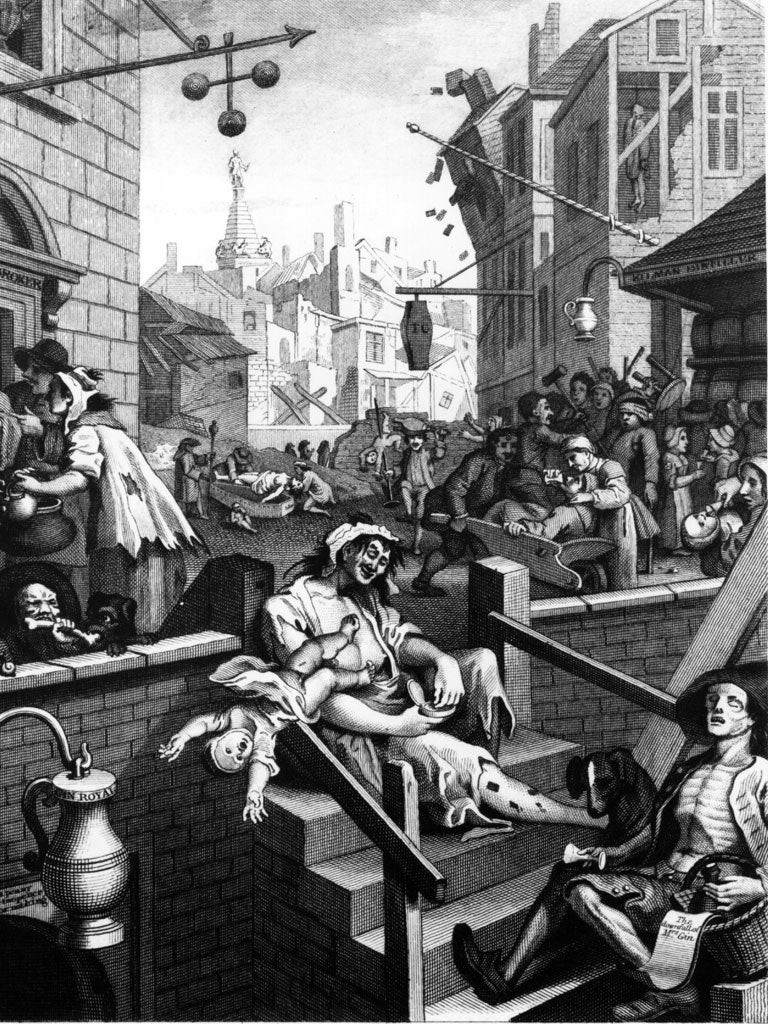

The upper classes have long indulged in moral panics about lower classes' drinking. Drunkenness was first made a crime in Tudor times when chroniclers became alarmed at widespread inebriety. In 1606, Parliament passed "The Act to Repress the Odious and Loathsome Sin of Drunkenness". In the 18th century came the gin epidemic, in which the adverts promised: "Drunk for one penny, dead drunk for two".

In the early 19th century, the owners of the mills in industrialising Britain lamented that drunkenness was a threat to production and growth. Victorian temperance followed. Pub licensing hours were first introduced during the First World War when Lloyd George, a noncomformist who had prominently supported the ban on the sale of alcohol in Welsh pubs on the Sabbath, outlawed the buying of drinks in rounds for fear it was causing hangovers among munitions workers.

Two distinct cultures dominate the drinking of alcohol. In the ancient world, the Greeks and Romans focused on wine, which was drunk, diluted, with food. There were Dionysian exceptions, but generally they admired self-discipline, frugality and simplicity. Children were given watered wine at meals and there was little social pressure to drink. It is a model that still holds sway in all the countries that once formed part of the Roman Empire – bar one.

Britain, by contrast, subscribes to a Barbarian culture of drinking. In these colder climes, the production of beer from local grain was as unpredictable as the Northern weather. Years of feast or famine built variation into alcohol consumption. Long periods of abstinence passed between binges. Beer, being a food, was drunk away from table. Public drunkenness was common and even acceptable. No wonder that to the Romans the term sabaiarius or "beer-swiller" was a grave insult.

It is popularly supposed that alcohol is to blame for the loud, loutish, promiscuous and violent behaviour on weekend nights in our cities. The social anthropologist Kate Fox disagrees. It is not drink that prompts the "Oi, what you lookin' at?" or "Hey babe, fancy a shag?" behaviour. Experiments show, she argues, that when people are drinking alcohol, they behave according to their cultural beliefs about how it will affect them. Those vary from one country to another, from the Mediterranean to the Barbarian, which is why behaviour shifts too. "Our beliefs about the effects of alcohol act as self-fulfilling prophecies – if you firmly believe and expect that booze will make you aggressive, then it will do exactly that," she writes. People do the same when given placebos.

Our real issue with alcohol is located elsewhere. Problem drinking is growing fastest not among the yobs but among the snobs. According to the Office for National Statistics, it is the upper and middle classes who are the most frequent drinkers in the UK. Some 41 per cent of professional men drink more than the recommended daily alcohol but it is middle-class women wine-drinkers who are growing fastest. They are 19 per cent more likely to drink heavily at home than are working-class women.

Wine consumption has increased five-fold since 1970. What was once a special treat has become an everyday comfort. And we have not swapped the Barbarian model for the Roman one. We have embraced both. One in four affluent couples in some areas are regularly consuming "hazardous" levels of alcohol. Professor Ian Gilmore, the president of the Royal College of Physicians, has said: "Alcohol-dependent middle-class people will be the next generation with serious health harm."

There is some dispute as to how many people are affected. Overall alcohol sales and consumption have fallen in recent years everywhere except Scotland. And some of the NHS statistics trotted out conflate primary and secondary causes of illness in a distorting way. But what is unarguable is that liver disease, unlike heart attacks and cancer, is the only major cause of death in Britain that is on the increase. It is up 25 per cent on the last decade. People are getting it younger, and women now as much as men. A significant swathe of the population is drinking itself to death.

Minimum Unit Pricing is not the solution for this. The real problem requires a response which is multi-faceted and complex. It is about changing a culture, and it will require education in schools, tightening licensing, changing brewing practice, reducing booze ads aimed at young people, and shifting peer pressure in the way that is being done by a social media campaign of reformed drinkers in Australia.

But that is hard. It is far easier to announce that multi-buy discount deals on super-strong chav lagers, white ciders, alcopops and vodka shots will be outlawed, while leaving the discount on a case of Château Lafite untouched. That is as snobbish as it is unfair on the vast majority of poor people who drink sensibly and whose pockets will be hit unnecessarily. It is like taxing all cars because a minority of drivers have accidents, or rather taxing old bangers while Rolls-Royces pay nothing – a trick that George Osborne missed in last week's "rob the poor to pay the rich" Budget. The battle over bargain booze, I am afraid, is just another episode in the Government's war of the chavs and chav-nots.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments