Owen Jones: We're now governed by the political wing of the wealthy

Cruddas's pledge to donors gives an insight into how power works in Cameron's Britain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Who runs Britain? It was a question memorably posed at the climax of the classic 1980s TV political drama, A Very British Coup, based on a book by former Labour MP Chris Mullin. Labour has swept to power under the radical leadership of Harry Perkins, a staunch socialist steelworker from Sheffield, causing uproar among the establishment. A coalition of press barons, City financiers, bought-off politicians and senior civil servants conspire to bring down the government, ending with Perkins apparently blackmailed into resigning on grounds of ill health.

But – in a televised address to the nation – the embattled Prime Minister veers off script, refusing to read the autocue, instead declaring: "You the people must decide whether you prefer to be ruled by an elected government or by people you've never heard of, people you've never voted for, people who remain quietly behind the scenes, generation after generation."

They're currently remaking the series, though apparently with a centrist Prime Minister, which would completely defeat the purpose of the drama. But that question of being ruled by "people you've never voted for" has become one of the dominant themes of our age.

We're governed by the political wing of the wealthy. That's not the view of a Socialist Worker headline writer: it's mainstream public opinion. According to a poll for The Independent earlier this week, two out of three voters think the Tories are "the party of the rich". Inevitably, that's partly because the majority of the Cabinet are privately-educated millionaires who would not look out of place in a 19th-century government. That's why George Osborne (the St Paul's-educated heir to a 17th-century baronetcy) slapping a tax on pasties – popular cheap nosh – strikes such a nerve. "It may sound trivial – but it is becoming symbolic of a divide between working people and a rich elite" – again, not the Socialist Worker, but the otherwise loyal Tory rag, The Sun.

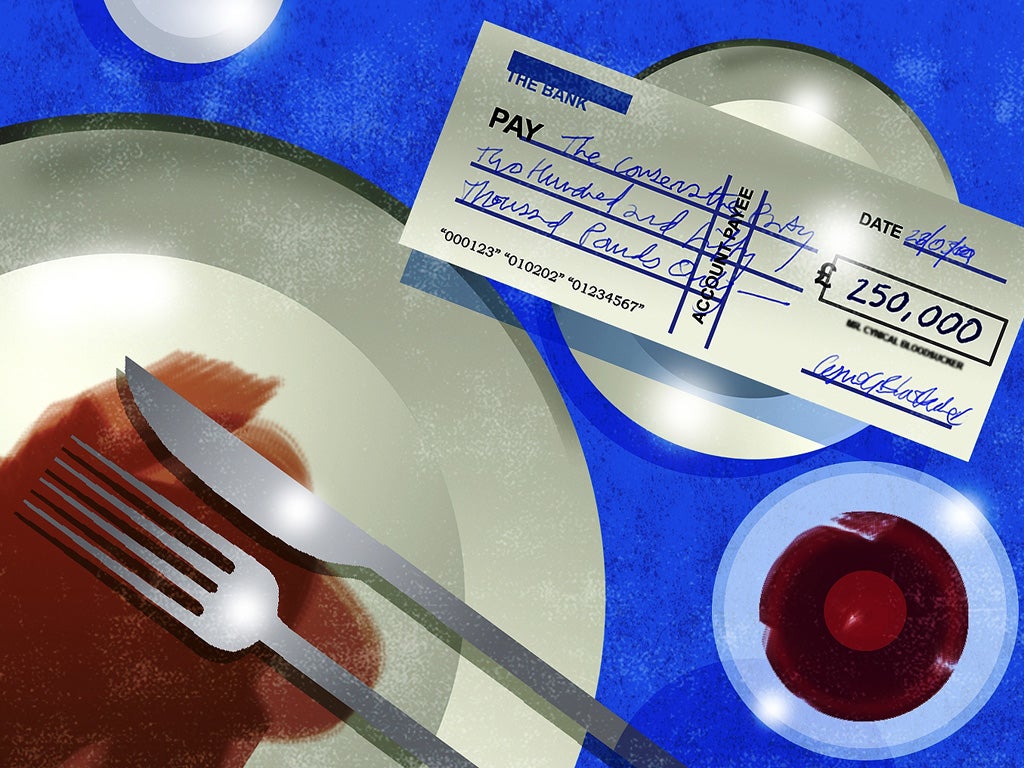

But it goes a lot deeper than the distance between the well-bred kitchen-supper eating Conservatives and the pasty-eating masses. It's the fact that the "Cash for Cameron" scandal has exposed the internal mechanics of how Toryism provides political representation for the upper crust of society, because "the people who remain quietly behind the scenes" have been thrust into the spotlight. Peter Cruddas is now persona non grata as far as Cameron's circle is concerned, but his pledge to "feed all feedback" of wealthy donors "to the policy committee" gives the rest of us an insight into how power works in Cameron's Britain.

Not that it should be much of a surprise: the political power of the rich, often disguised and subtle, has become more overt as the economic crisis has worn on. The British Chambers of Commerce lobbying operation has been in overdrive since Cameron was installed in Number 10, and their wish-list is making the statute books. They demanded the hiking of fees for workers taking their employers to an industrial tribunal – lobbying Tory minister Jonathan Djanogly back in December 2010 – and they have been granted it. They have pushed to make it easier to sack workers, and have already won the doubling of the unfair dismissal period.

One of the donors named as having a private dinner with David Cameron is Michael Spencer, chief executive of interdealer broker Icap, a multi-millionaire who has boasted that Tory ministers assured him that any European financial transaction tax would be vetoed. When he was Tory treasurer in 2009, he reassured financiers that the Conservatives "cherish the City" and predicted Cameron's government would scrap the 50p tax and deliver an even bigger corporation tax cut than promised: and so it came to be.

John Nash, the chairman of private health care company Care UK, bankrolled the private office of Health Secretary Andrew Lansley to the tune of £21,000 in the run-up to the election. All perfectly legal, of course, but the company can expect to recoup that cash several times over from Lansley's attempt to privatise the NHS. Adrian Beecroft, a former venture capitalist who has donated £593,076 to the Tories since Cameron became leader, was commissioned by Number 10 to write a report calling for "slacking" workers to be sacked at will. And so on.

The interests of the wealthy have always been on a collision course with democracy, forcing them to attempt to subvert it – and the Tories have provided the ideal vehicle for it. After all, the party spent most of the 19th century resisting giving working-class people the vote: as Tory Prime Minister Lord Salisbury once put it: "First-rate men will not canvass mobs, and mobs will not elect first-class men."

But fighting the corner of a tiny percentage of the population is tricky when everyone has the vote,hence these secretive attempts to manipulate the democratic process. As they have become adept at doing, the Tories are attempting to deflect the current crisis on to the Opposition. "What about the trade unions bankrolling the Labour Party?" they cry. But there is a world of difference between multi-millionaires who hand over huge donations and enjoy private dinners with the Prime Minister, and millions of working people giving a small contribution from their pay packet in the hope of securing a political voice. The real scandal of the link between unions and Labour is how little rank-and-file members have got in return. The political power of a supermarket checkout worker paying in to her trade union political fund is incomparably smaller than the influence of Michael Spencer, John Nash or Adrian Beecroft.

But a political opportunity has presented itself to Labour. Ed Miliband is no Harry Perkins, but Labour has flourished most when the Tories' secretive links to the wealthy and powerful have been exposed – over News International, the banks, and now the "Cash for Cameron" scandal.

As Tory financiers and business people continue to stage their "Very British Coup", Miliband could rediscover Labour's purpose – and provide the same service for working people that the Tories do for our ever-wealthier elite.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments