Once upon a time, there was a man who liked to make up stories ...

With their tiny heroes and cruel villains, books by Roald Dahl never date

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

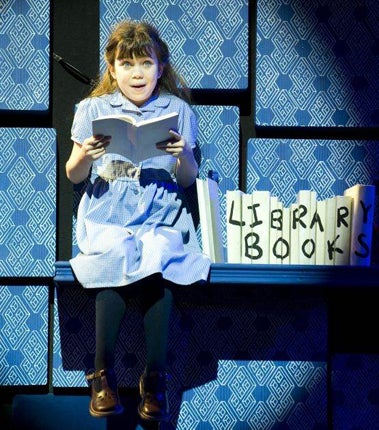

Your support makes all the difference.The Christmas stage version of Roald Dahl's children's story, Matilda, has been hailed by one critic as "the best British musical since Billy Elliot".

It turns out to have that quintessential panto quality of blackness-and-whiteness, of appalling villains and a small but clever heroine.

For this, some credit must go to the director, Matthew Warchus. But a rather larger share must be attributed to Matilda's begetter, Roald Dahl, one of the greatest storytellers for children of the 20th century. Dahl is probably responsible for as many children becoming readers as that other prodigious author Enid Blyton.

But whereas Blyton's books now seem of their time, Dahl's stories for children, with all their diabolic subversiveness, have turned triumphantly into the 21st century and show no sign of losing their appeal. This stage version of Matilda is only the latest attempt to translate Dahl from prose into other media: among other versions, there have been two films of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (the first of which the author detested, for giving more attention to Willie Wonka than to Charlie), there has been a (very bad) film of Matilda, and there was a recent film version of The Fantastic Mr Fox, with the unusual twist that one of the young foxes appears to be gay.

But the stage and screen versions of the books will never surpass the originals – which is not to say that this is always the case, for Roald Dahl played a part as scriptwriter in turning Ian Fleming's story, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang , into a far superior film. It is partly because of Dahl's deceptively simple prose.

But it is also because they already have their own visual expression, from which they can never really be detached, in the equally subversive illustrations of Quentin Blake. When children think about The Twits or Matilda, they think about the story and the pictures in pretty well the same breath.

Dahl's parents were Norwegian, which meant that his mother told him folk stories when he was small, including tales about trolls. He was born in 1916 in Cardiff, and the Norse folk tales were part of his formation, along with Kipling, Marryat and Dickens. And that quality of the small against the great, of sharp-witted humans against trolls, of black and white – for folk tales do not admit of shades of grey – is discernible in his later writing.

But he was also a child, with no very great regard for authority. At the age of eight, his primary school headmaster caned him and four friends for putting a dead mouse in a jar of gobstoppers in the local sweetshop owned by a "mean and loathsome" old woman called Mrs Pratchett. You can see here something of the imagination that brought forth the foul tricks that Mr and Mrs Twit would play on each other.

There were other reasons too, for his keen sense of justice. His latest biographer, Donald Sturrock, has written about the grim misery that characterised his time at Repton, the public school where the savagery of older pupils to younger ones, and the coldness of masters to boys, almost drove him to suicide. The cruelty of the place revolted him. You could say he got his own back on authority in his books, in which the bullying of the vulnerable by the strong and powerful and stupid attracts ruthless retribution. Still, his education left him with a clear, effective prose style.

As for so many of his contemporaries, his formative experience was in the Second World War, in which he was initially a fighter pilot, ending his flying career as a wing commander. But it was as a British representative in the US during the war – spying was perhaps the wrong word for his propaganda work on behalf of Britain, given, as one of his daughters put it, that he "gossiped like a girl" – that his life took on a James Bond aspect.

It is given to few young men of 27 to sleep with glamorous older women for his country, but this is pretty well what Dahl did. He was in New York and Washington to put the British case to the Americans, working for the Canadian buccaneer, William Stephenson, and he did so, in part, through affairs with influential women. He was always very tall, with the glamour of a fighter pilot, and he was sought after. In 1949, he wrote a revealing piece in the Ladies' Home Journal on the nature of desire, in which he ascribed 70 per cent of it to sexual attraction and 30 per cent to mutual respect.

His first marriage, which lasted 30 years, was to the beautiful American actress, Patricia Neal; they had five children. But his only son, Theo, was terribly injured when a cab careered into his pram in Manhattan; it was thought he would not survive or would be irreparably brain damaged. Dahl's capacity for decisive action came to the fore; he commissioned a friend to make a valve that helped clear the child's brain of fluid, which helped his partial recovery.

He returned with his family to Buckinghamshire, where, his wife said, they had perhaps the happiest two years of their marriage. Then, his daughter Olivia, succumbed to measles encephalitis and died, aged seven; he was traumatised by the loss. The BFG, was dedicated to her; Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to Theo.

Something of the nature of Dahl as a father emerged in a memorably savage riposte he wrote to a critic of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, as having a bad effect on children. "I believe that I am a better judge of what stories are good or bad for children", he wrote. "We have had five children. And for the last 15 years, almost without a break, I have told a bedtime story to them as they grew old enough to listen. That is 365 made-up stories a year, some 5,000 stories altogether. Our children are marvellous and gay and happy, and I like to think that all my storytelling has contributed a little bit to their happiness." In fact, after Olivia's death he was more aloof as a father, which is not to say he was uncaring.

That tragedy was followed by another, when Patricia had an aneurysm, which left her a shadow of her glamorous self. Dahl threw himself into her rehabilitation with his old vigour, commissioning friends to provide physical and mental stimulation; Roald the Bastard she called him at the time, but the work paid off. It was not enough however, to save their marriage, which ended in divorce in 1983 when he married his mistress, Felicity "Liccy" Crosland. The marriage lasted until his death in 1990.

Dahl was, of course, a writer for grown-ups as well as children: his short stories are terse, macabre and with a redemptive element of humour. But it is his children's books that have made him immortal; Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, The Twits and The BFG are part of almost every child's formation as a reader. Quentin Blake gets close to the heart of their appeal. "He was mischievous", he told me. "A grown- up being mischievous. He addresses you, a child, as somebody who knows about the world. He was a grown-up – and he was bigger than most – who is on your side. That must have something to do with it."

You can add to his cracking narration the folk elements of his stories, that is to say, their moralism and judgmentalism, qualities that children instinctively respond to. Villains are clearly labelled as villains, which makes the satisfying completeness of their horrible ends – and they are usually seen off with memorable finality – all the more gratifying. And there is, too, the fairytale element of the weak vanquishing the strong. Quentin Blake recalls how important it was to Dahl that Matilda should be "titchy"; it made her triumph more complete: "Being very small and very young, the only power Matilda had over anyone in her family was brain power...".

Perhaps it is that notion of the weak being strong through qualities of courage, cleverness or kindness that gives the stories perpetual appeal, except that Dahl is always funny with it. Red Riding Hood, in Revolting Rhymes, confronted by the wolf, responds: "The small girl smiles; one eyelid flickers/She whips a pistol from her knickers/And bang bang bang she shoots him dead ...". That's the spirit. And that's why Dahl will be read with relish a century from now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments