Michael McCarthy: Echoes of the day horror was visited on Hungerford

The parallels with Michael Ryan's rampage in 1987 are striking

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

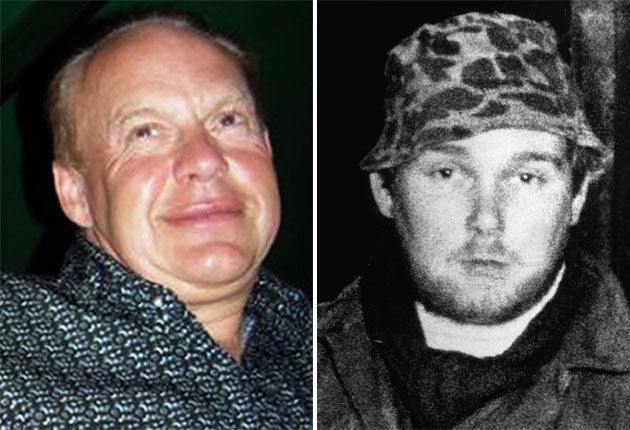

Your support makes all the difference.A gunman going on a murderous shooting spree in and around a small English town is hardly an everyday occurrence but unfortunately we have been here before. Twenty-three years ago Britain woke up to the largely-American phenomenon of the firearms rampage when Michael Ryan, an unemployed labourer and gun fanatic, perpetrated a massacre in the quiet Berkshire market town of Hungerford.

The similarities with yesterday's bloodbath in Cumbria are striking, with in each case the gunman picking out more than 30 random targets over several hours and blasting them, before shooting himself dead. The only difference is in the percentage of fatalities: Derrick Bird shot 12 dead yesterday and wounded 25, but on 19 August 1987 Michael Ryan wounded 15 yet killed 16 people outright before turning one of his several guns on himself.

He was able to do that because among his collection of six legally-held weapons, he had two high-velocity semi-automatic rifles capable of rapid fire, a US M1 carbine and a Chinese version of the Russian AK-47 assault rifle, and it was these he used, with deadly effect, to carry out his merciless Market Day assault on Hungerford's residents.

As a direct result of his actions, the Firearms Act was amended in 1988 to ban the private ownership of semi-automatic rifles and restrict the use of shotguns with a magazine capacity of more than two rounds.

That will be cold comfort for the people of Cumbria this morning, just as it was cold comfort for the people of Hungerford, who, it transpired in the subsequent inquiry, had been let down in several ways, with extensive criticism being made of the speed of response to the incident by Thames Valley Police.

The local police station was being renovated and had only two telephone lines working on the day and, furthermore, the local telephone exchange could not handle the amount of 999 calls being dialled; the police helicopter was being repaired; the force firearms unit was training 40 miles away.

But in truth, it would have been difficult for any police force to grasp immediately the scale and nature of what began to unfold that day, which was something entirely outside the experience of British police, other than in Northern Ireland.

Ryan, who was 27 and lived with his mother, a school dinner lady, began his massacre for reasons no one will ever know when he encountered a young mother, Susan Godfrey, picnicking with her two small children in Savernake forest. He shot her 13 times in the back. He then drove back to Hungerford, set fire to his own home and began to move through the streets of the town shooting anyone he encountered: people mowing their lawns, walking their dogs, driving their cars, including his own mother, Dorothy, and the first policeman to arrive at the scene, PC Roger Brereton.

He finally retreated to the empty John O'Gaunt Secondary School, which he had himself attended, where he was surrounded by armed police and where, eventually, he shot himself.

As a reporter covering the incident that day for another newspaper, I was struck by two things above all. The first was how difficult it was to make sense initially of what was actually happening, to grasp the unthinkable nightmare unfolding in the quiet market town. The second was the eventual shock of realising what had taken place; I still remember the Chief Constable of Thames Valley, Colin Smith, walking up to the press briefing in the street at 8.10pm on that warm August evening and beginning to say: "It now appears that 16 people have been shot dead..." and the gasp which followed from the assembled reporters.

It was unthinkable then. Not any more of course. In Dunblane, nine years later, it was 17, and yesterday it was nearly as many.

But that evening in Hungerford, in our relatively quiet and relatively civilised country, some sort of awful psychic boundary was definitely crossed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments