Ian Blair: Assisted dying needs a change of heart

The law is unclear and needs changing when those wanting to end the suffering of their loved ones still fear being sent to prison

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Efforts to bring the perpetrator to justice are a natural corollary of the commission of crime. If someone steals from a newsagent, we assume the thief will be investigated and face the courts, perhaps to receive a sentence of community service or more; if a drunk-driver kills a pedestrian, that driver's actions will be investigated and perhaps deserve a prison sentence. But what if the case involves acting illegally but out of love and compassion: what if the law has not kept pace with modern life and modern science?

This is the case with the law regarding assisted dying – and it was the aim of the Commission on Assisted Dying, which reports this week, to investigate the current law on this subject and ask whether it needs to be changed. It does.

Assisting someone to die is illegal. The aiding or abetting of another's suicide, which could include the facilitation of travel to another country where it is legal, is punishable under the Suicide Act 1961 by up to 14 years' imprisonment. However, despite more than 30 cases being brought before the Crown Prosecution Service since February 2010, there have been no prosecutions.

So that's all right then? No, it isn't. The discretion over whether to prosecute, at present, resides with one individual at the top of the Crown Prosecution Service. However, the Director of Public Prosecutions cannot make any ruling until a full police investigation has taken place, which means that those involved in such cases not only have to deal with their grief but must also do so under the threat of prosecution and imprisonment, the possibility of arrest and the certainty of intrusive searches of property and questioning.

I am no stranger to the difficult decisions that police officers face on a daily basis. But the evidence I have seen during my time on the Commission on Assisted Dying has convinced me that the law as it currently stands is failing both those whom it seeks to protect and those tasked with enforcing it.

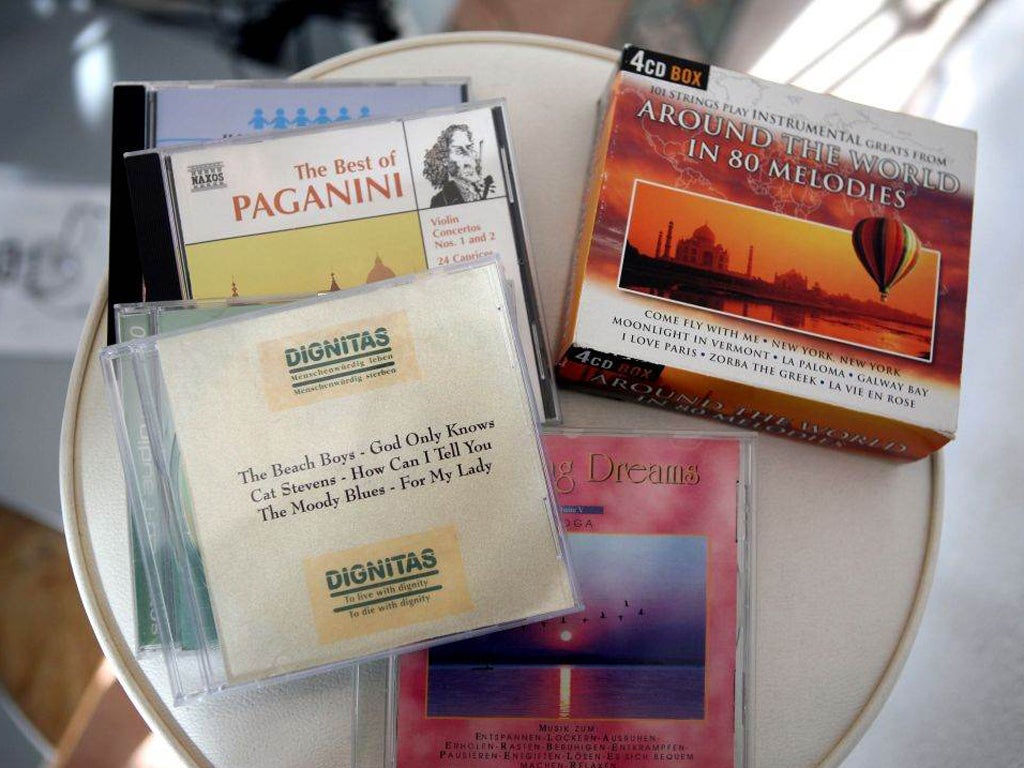

As a commission, we heard how Alan Cutkelvin Rees travelled with his partner, Raymond Cutkelvin, to Dignitas in 2007. When he returned alone, living with the threat of a visit from the police proved too much. He was forced to pursue a very public means to seek closure and begin his grieving. "Come and arrest me," Rees said through the Evening Standard, and, sure enough, the police reacted. Until this point, though the police had been made aware of Mr Cutkelvin Rees's experience, they had not investigated the issue, but he knew of no reason why they should not begin to do so at any time.

The difficulty faced by police officers was made clear in the evidence presented by Detective Inspector Adrian Todd and Detective Constable Michelle Cook, of West Mercia Police, who investigated the case of Daniel James. At the age of 23, James, who had suffered a catastrophic spinal injury playing rugby, chose to travel to Switzerland accompanied by his parents. The officers' investigation into Mr and Mrs James's role in assisting Daniel to end his life there clashed directly with their natural human empathy for the family and placed them in an impossible position. DI Todd told the commission that James's parents "were really concerned, they genuinely thought they were going to go to prison. There was nothing we could say to them that would reassure them because we didn't know". In the end, Mr and Mrs James were met with no charges, but this did little to assuage the fear and grief they had been left to suffer in the interim six weeks it took to discover whether or not they would face legal action.

But there is worse. The testimony of Chris Broad before the commission was one of the most poignant of many moving and terrible stories. His wife, Michelle, decided not to tell him or anyone else exactly when she had decided to die, nor to have anyone with her, including Chris, when she did so, for fear that that would increase his chances of being prosecuted. It was obvious that the thought that she had died alone, uncomforted, was a bitter additional aspect of her husband's grief.

I am proud to say that, in each case, the police officers were praised for the sensitivity that accompanied their professionalism. But this does not mean that we should be satisfied with the current arrangement.

The incoherence of the current law on assisted suicide also drew criticism from healthcare professionals. In particular they focused on the lack of clarity about which actions constitute "assistance" under the DPP guidelines, and whether, for example, providing Dignitas with medical information about a patient could make professionals liable for prosecution. As it stands, the Medical Protection Society advises doctors that they can provide medical records, but not a report. However, other legal experts offer conflicting advice, and the law does not explain whether it is the duty of a doctor to inform the authorities about someone's intention to seek an assisted suicide. As Dr Lillian Field of the MPS put it: "Should they disclose? When should they disclose? What is their position in relation to the law in this regard?" Healthcare professionals are caught between the nebulous state of the law and a presumed duty of confidentiality to the patient.

This snapshot of evidence received by the commission on the legal and psychological challenges facing those already in distressing circumstances describes a system that is incoherent and unsafe. At a time when they should be grieving, under the current system relatives of loved ones are forced into a world of uncertainty that leaves the police and prosecutors torn between good practice and natural human sympathy. The current settlement relies on people taking a leap of faith that the DPP will respond compassionately, trading off their respect for a loved one's dignity against the fear of prison.

The approach of the current DPP, Keir Starmer, to this sensitive issue has been rightly compassionate, but another DPP could change the guidance. We are in a situation where the letter of the law prescribes severe punishment, and yet our civilised society rightly fails to have the stomach to prescribe it.

The Commission on Assisted Dying will have many recommendations – and many caveats – to make when it reports later this week. The creation of a humane, coherent and enforceable framework of law will be one of them.

Lord Blair of Boughton is a former Metropolitan Police commissioner and a member of the Commission on Assisted Dying, which will publish its final report and recommendations on Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments