Ian Birrell: Big Pharma's demise is nothing to celebrate – our health is in their hands

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

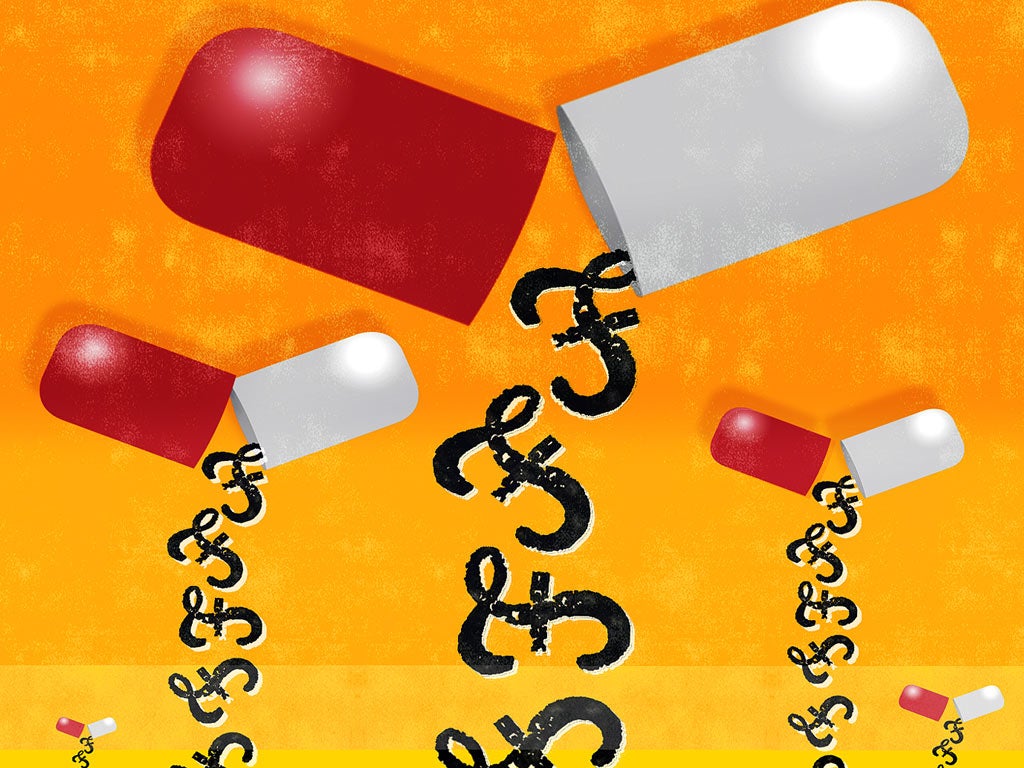

Your support makes all the difference.You may not have heard the screams, but this was the week the drug industry fell off a cliff.

The most profitable medicine in history, which has been earning up to £8bn a year, came out of patent in the world's biggest market on Thursday. And it was just one of four bestsellers that lost protection in the United States that day.

Lipitor is the ultimate blockbuster drug, an anti-cholesterol pill that tackles the effects of modern lifestyles and helped Pfizer to be the world's biggest drug dealer. It comes out of patent across Europe in May. The company is spending a fortune to persuade patients to continue taking its medicine, but cheaper generics will savage income from this drug.

It is the most dramatic example yet of how Big Pharma is hurtling over the so-called "patent cliff", leaving the industry in a big panic. Until recently, this was the most profitable legal business on the planet; now it faces an uncertain future. It is losing control of 10 mega-medicines this year alone and dozens more over the next few years.

This is, of course, cause for celebration since it cuts the soaring costs of healthcare, which on current trends will consume more than half our GDP by the end of the century. But it is not only bean-counters who will be delighted to see pain inflicted on these behemoths.

The drug giants are almost universally hated. They are up there alongside arms manufacturers, bankers and oil firms in the pantheon of corporate evil, a villainous target for thriller writers, film-makers, polemicists and politicians. Even the Republican candidate had a pop at them in the last US presidential election.

But we need to grow up and wake up. This is one of the most important industries in Britain, and it is undergoing a technology-driven revolution as profound as those confronting the music and newspaper industries. In these tough times, we simply cannot afford hostility to "grubby" commerce, let alone our usual insouciance over science.

Big Pharma has, of course, been its own worst enemy, with a wretched history of overcharging, tainted trials and the like. But Thursday was also World Aids Day, a reminder that it was primarily this most capitalist of industries that removed the death sentence from an Aids diagnosis.

Such facts offer another dose of painful reality for those anti-capitalist protesters pitching tents at St Paul's. Indeed, for all the allegations of ripping off poor countries, the loathed big guns of the pharmaceutical industry can claim some credit for the improving health and increasing longevity of the human race across the globe.

They also play a vital role in Britain's economic health, with life sciences employing 165,000 people and more than 4,000 firms turning over £50bn a year. Two of the world's biggest drug companies are British – but they, too, are staring into the abyss. Astra-Zeneca, for example, has two drugs coming out of patent protection in the next three years that account for nearly one-third of its sales.

Big Pharma's business model is at breaking point. Not just because regulators are more risk-averse and health services demand cheaper drugs and more generics. But because they can no longer just hire tens of thousands of researchers to create new generations of blockbuster drugs that will work on vast swathes of the population, earning back the billions they cost to develop and trial.

We have moved into a new era of medicine thanks to astonishing advances in biology and genetics. Perhaps the best example is paracetamol, around since the 19th century and one of the most commonly used household drugs. But only this year have researchers at King's College London finally understood how it works on the human body, opening up the prospect of safer and more effective painkillers.

The consequence of such advances is drugs that work less like a blunderbuss and more like a sniper's rifle, aiming their medicinal bullets at smaller groups of people. So we have a drug such as Herceptin, so effective for treating breast cancer – but only for women with a particular receptor on their cancerous cells.

This technological revolution, based on complex biology rather than just firing off chemical compounds, is forcing drug companies to reinvent themselves. They are slashing research jobs – 4,500 in Britain alone in the past two years – while closing large laboratories and setting up venture capital arms to spot the next big thing.

Many of these should be found in Britain, given this country's astonishing record of scientific creativity, with more than 80 Nobel prizes – 25 claimed by Cambridge University alone – and four of the world's top 10 research universities. But can we exploit this scientific strength to remain at the forefront of the industry – or will we be left behind by hustling new players such as India, Israel and Singapore?

This issue has been greatly exercising David Cameron. He will make a speech on the subject on Monday, praising the role of life sciences and announcing new support for medical start-ups. It is a good start. But we remain locked in the past in many ways. Would he dare, for example, to allow drugs to be given to patients before the conclusion of clinical trials if there are no other treatments available, something that makes sense in a world of personalised medicines?

Or to insist that the NHS opens up access to its databases unless patients opt to keep information private? This idea is being pushed by cancer charities and would take advantage of having such a vast, centralised health system.

There also need to be cultural changes. What about funding doctors and scientists to study at business schools, as in the US? After all, in other countries experts go from academia to business and back to academia quite happily. In this country, despite improvements, the two worlds remain too far apart, with insular universities and scientists more focused on seeing ideas in print in academic journals rather than in profit in commercial ventures.

Britain needs to embrace its life scientists, who are doing such remarkable work with so little credit. But these scientists need to embrace capitalism, collaboration and to be unafraid of commerce. And we all need to embrace an unloved industry that holds the key to our future health and wealth.

twitter.com/@ianbirrell

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments