Guissou Jihangiri: Fame, fortune and a female force in Afghan politics?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To use women candidates as proxies in tomorrow's elections is extremely cynical. Unfortunately, it is not an entirely new phenomenon. All the Mujaheddin parties had female members. And there have always been well-known female elites in Afghan political life who got their positions because they were the wives or daughters of powerful men or clans like the Haqqani network or General Dostum's circle.

What is ironic is that the 25 per cent quota of seats in parliament guaranteed for women by the current constitution was something that the international community wanted, because the plight of women under the Taliban was such a sensitive issue with public opinion in the West. Yet, while it was intended to redress the wrongs done to Afghan women, it risks having the completely contradictory effect of helping to perpetuate a system whereby political deals are brokered by a handful of strongmen. Powerful forces want to get their hands on the 25 per cent so they need women candidates to stand, even if they will never actually advance the rights of women or girls while in parliament.

But if some women are the pawns of warlords, other groups too are using women for different reasons. Nearly every outside agency, the UN, the NGOs and the foreign embassies also have their "favourite" lists of candidates which they will hope to influence after the vote.

It was dispiriting to see how women representatives to the June peace jirga were then asked to talk to the mothers of the Taliban, to persuade them to get their sons to lay down their arms. If such a futile and in my view ridiculous task is the limit of how we want to involve women – while the real decision making is done elsewhere – then their political engagement will remain nothing more than tokenism. The great shame is that there are possibilities for a younger generation of educated Afghan women seeking political power. One real positive is that Afghan people have become more used to seeing women in parliament, even if they haven't been able to advance the real concerns of women.

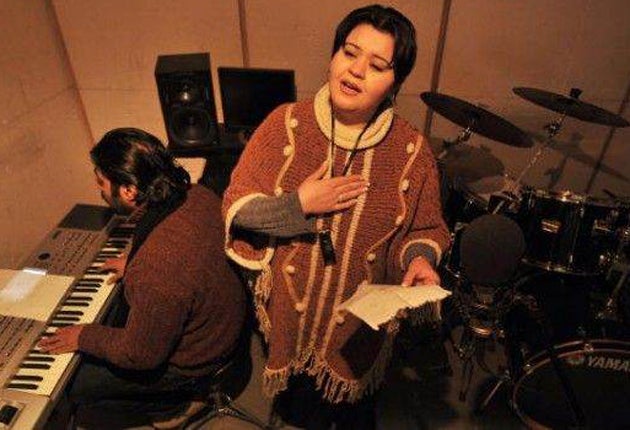

Among tomorrow's candidates is Farida Tarana, a singing contestant on the television talent show Afghan Star. A sportswoman is also standing. Both are, rightly, using their fame to promote their candidacies and are not relying on powerful groups or banks for backing. Few if any of my friends, younger, educated, city-dwelling Afghans, will be voting tomorrow. They fear this election is so flawed as to be meaningless. Yet, in a country where the average age is 19, women candidates, independent of powerful cabals, could help address the crisis of legitimacy afflicting the older political groups and reverse the dangerous decline in public participation.

The writer works for the Kabul bureau of the International Federation of Human Rights

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments