Robert Fisk: We should mourn these desert staging posts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So what, readers, is a "caravanserai"? In Persian (or Dari), it is "karvansara", in Turkish, "keravandaray" – yes, from which we get our "caravan" – and it is an inn (or "pub" as we might call it) and I am inspired this week to praise the "caravanserai" because it is where we all met in the age before steamships and aircraft. Buddhist, Jew, Muslim, Christian, we would all meet there.

Usually, their outer walls were made of black and white marble. There is a caravanserai just south of my home in Beirut, at Saaderat, south of Khalde, much splattered with machine-gun holes, but clearly the last stop on the road to Beirut, the last secure resting-place for camels and horses before you reached the "Bourj", the great Ottoman gate to the second city of Syria (before the French cut it in half).

I have a great love of the caravanserai of Diyabakir in Turkey. Of this town, it was said by a British consul that "the walls of the city are black, the dogs are black and the hearts of its people are black". I do not agree with the British consul. I was arrested there by the Turkish police in 1991 for "defaming" the Turkish army.

I had written – accurately – that the Turkish army had stolen blankets and food from Kurdish Christian refugees fleeing Saddam Hussein's army. This was true. The Turkish police arrested me. And the chief inspector of Diyabakir (noting my book on the Armenian genocide in my bag and realising that I knew the truth about the 20th century's first Holocaust, treated me with great respect).

"You are not my prisoner," he said. "You are my guest."

Well, up to a point, inspector. In fact, he had to ask the manager of the Caravanserai Hotel – a Kurd – to translate, since he did not speak English and I did not speak Turkish. This resulted in a weird conversation in which he could not ask the questions he wanted and I could not give the replies he didn't want about the Armenian genocide and the Turkish army.

It ended up with me telling the inspector that my father regarded Mustafa Kemal Ataturk as a titan, but that I could not understand why Ataturk's soldiers should have so betrayed his memory as to have stolen food and clothes from refugees. At this point, the inspector put his arm round my shoulder and insisted that the local Turkish newspaper reporter took a picture of us to show what good friends we were.

I was taken by the cops (who had black coshes in their hands, by the way, so don't think they were all nice guys) back to the Caravanserai Hotel where I had to flush my Armenian contacts book down the loo while a policeman stared through the keyhole of the lavatory before being put on a plane back to Istanbul with a detective who had never travelled by air before and whom I had to tell, en route, that he would arrive safely.

But the hotel in Diyabakir really was a caravanserai. Its entrance was wide enough for camels or horses. It was lined with black and white marble. It was a fortress for travellers, a place of rest and comfort.

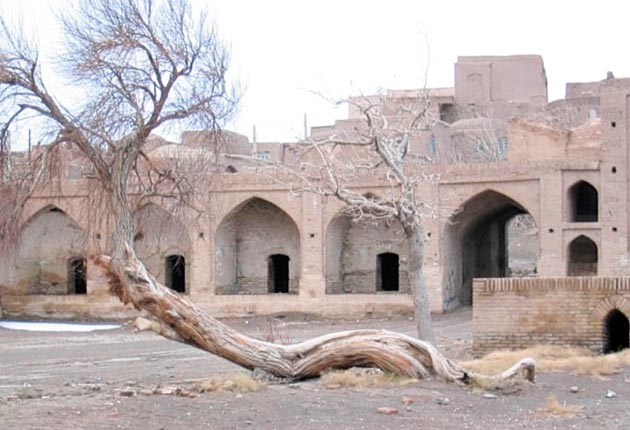

So now I move to my friend Tom Schutyser, a Belgian madman who is obsessed (rightly) by caravanserai. He has taken the most magnificent black and white photographs of these airports of the desert, voyaging down the Silk Road from Iran through central Asia (Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan) to China. As he writes in his beautiful booklet to accompany his images, "In northern Iran, these silent, solemn ruins of caravanserais languished in eerie, desolate, motionless, desert winter landscapes. They are a reminder of the prosperous eras of the Silk Road along which trade, inventions, diplomacy, religions and culture were exchanged between China, the Western world, the Middle East and Central Asia."

There were thousands of these caravanserais, staging posts across the known world, accommodating, as Schutyser says, traders, pilgrims and travellers. They were for commerce and for multicultural meetings. Some caravanserais had their own translators so that Persians and Indians and Arabs (and Brits, too, of course) could speak to each other.

In Jordan, in Iran, here in Lebanon, I come across these places of peace and solitude and happiness, usually in ruins. And oh, if only we could re-create their world. What airport today will give you a translator? What railway station will tell you what your fellow traveller is saying? Some caravanserais had libraries – books – in which a tired family could read of their fellow guests. How we should miss these places.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments