Robert Fisk: Injustice in three dimensions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I am now the proud owner of a wooden "Perfecscope". Do not, readers, Google.

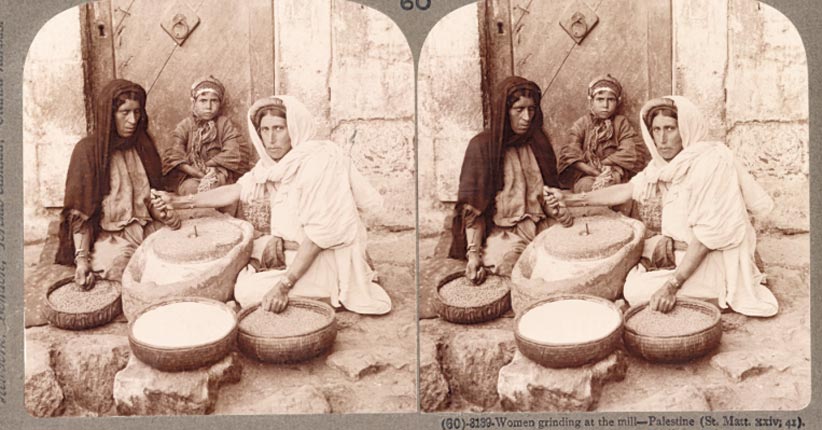

I will tell you what it looks like: a cross between a periscope and a horse's feed-bag; mine is patented in the "USA, Canada, France, Great Britain, Germany, Austria, Belgium" and warranted by "Underwood & Underwood, New York". In front of wooden goggles containing two glass eyepieces, there stretches a thin plank of narrow wood and a smaller bar crossways at the end with two small metal clips. Into this I can place a card bearing two identical photographs of Palestine – each more than 100 years old – and when I peer through the eyepieces, I perceive two facts: that the peasants stand out in three-dimension against the fertile fields and trees of Ottoman Palestine; and that this ancient province was not the "barren" land which Israeli song and legend makes it out to be.

My Perfecscope is a very early version of those 3D red-and-black plastic-in-cardboard lenses through which we used to watch movies, and read – if that's the right word – cowboy comics. But the characters in my pictures do actually appear standing in front of or behind buildings, castles, walls, ancient wells and valleys in Jerusalem, Mount Saba, Bethel, Jaffa, the Dead Sea... I have a separate set of cards from Egypt, in which the pylons of Thebes and the tombs of the kings stand out in similar dimensions, ancient tourist guides obligingly providing the nearest perspective.

Now I have to explain how I came by this wondrous machine. It was given to me in Woodstock Church in Oxfordshire by a former arch-Zionist, a gift from a Jew – recording the largely Muslim population of Palestine – handed over in front of a Christian altar, to a reporter who routinely gives his religion as "journalism". Gabriel "Gabby" Dover was the gracious donor – he had been attending The Independent Woodstock Festival – and you needn't Google him either. For 72-year-old Gabby just happens to be one of our most controversial (in the best sense of the word) geneticists, who invented the phrase "molecular drive", spent a quarter of a century at Cambridge's department of genetics, and is emeritus professor of evolutionary genetics at Leicester.

I should say at once that, being neither a "techie" nor a scientist, I beg Gabby's forgiveness if I get his principal thesis – advanced in his book Dear Mr Darwin: Letters on the Evolution of Life and Human Nature – a little too simplistically. It's this: that it is neither nature nor nurture at the heart of anyone; it is not amenable to unravel what happens to the fertilised egg. "You usually identify with a kin group," Gabby tells me later. "But if I identify with thousands of people watching a match played by Manchester United, I may, in normal circumstances, have nothing in common with these people." In other words – so I try to force out of him – even if you have 100 people and they came from identical sperm, they will still be different.

It might be said of Gabby Dover that he, too, deviated from his own kin group, finding himself supporting Medical Aid for Palestine – an act which prompted a close Jewish academic friend to ask Gabby on Monday why he wasn't supporting medical aid for Israel. There was, Gabby recalls telling his friend, a "wealth gulf" between the two peoples. In truth, Gabby's own family background is almost as complex as the putative third evolutionary force which, according to him, operates distinctly from natural selection and genetic drift. It was his mother, a Fabian socialist and pioneering Zionist, who encouraged Gabby to become a kibbutznik; she had met his father, born into a cultivated family of Sephardi Jews from Damascus, in 1937 – but he, again according to Gabby, "hot-footed it off to Palestine" after his birth.

For Gabby, too, there was no need to be brain-washed about Zionism. His fellow youth leaders were "role models" and he worked happily in the early 1960s with his very young wife at Kibbutz Nachshonim, whose economic future rested on the successful farming of a large and very fertile valley which, a few years earlier, had belonged to Palestinians. Gabby has since written to me about his story so, beside his letter, I pull out more of his picture cards and insert them in my wooden Perfecscope. There are Palestinian Arab fishermen off a distant Haifa, women in Palestinian traditional dress in a Hebron orchard, others in headscarves barley harvesting near Bethlehem, a procession of Arab Christians at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There are a few photographs of bearded Palestinian Jews, including an ageing rabbi; members of a Jewish population which, in the 1900s, represented less than 10 per cent of the population. But the three-dimensional greyness of these pictures in my Perfecscope cast a disturbing, tragic light across the landscapes. The middle-aged Arab women would live to hear of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, though only the children, staring innocently at the camera, would – in middle age, of course – live to experience the Palestinian exile and the creation of the Israel to which Gabby journeyed.

In a deeply moving letter to his granddaughter, he describes his own partial conversion when, after being long convinced that "we Jews had arrived where we belonged", he had to drive a tractor out of his kibbutz, turning right at the gate and dumbing rubbish in a pile of garbage down the road. "I decided to turn left and take the tractor towards the border – a route that was rarely taken, and somewhat forbidden, by anyone in the kibbutz. Within a couple of miles I came across two groups of white stone buildings and mature eucalyptus and fig trees, blown apart and empty – once the cool and no doubt beautiful homes of Palestinians... How could I not stop and think about this major dislocation right on my very doorstep... I became a ghost in a ghost town that no one ever spoke about."

This wasn't the only reason Gabby left Israel. There was "the growing existential feeling that I couldn't live a life where everything was predicted in advance". But the visit to the abandoned village remained central to his experience. "It reveals how small things lead to other things," he told me this week. "It was a realisation in such a stark manner, the Arab homes all blown up and me alone, seeing that. I'd never been there before."

So I looked once more at that lost world of Gabby's, and all the figures stretching away 3D across the fields and hills. Their fate was already set in drawing rooms in London, decided by the coming war which would finally take down those tiny Turkish flags in the pictures. Underwood and Underwood – and Gabby – gave me the 3D ghosts of the Palestinians. Of course, he had to turn left at the gate to find them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments