David Quantick: A little bit of nonsense is the secret of a sane life

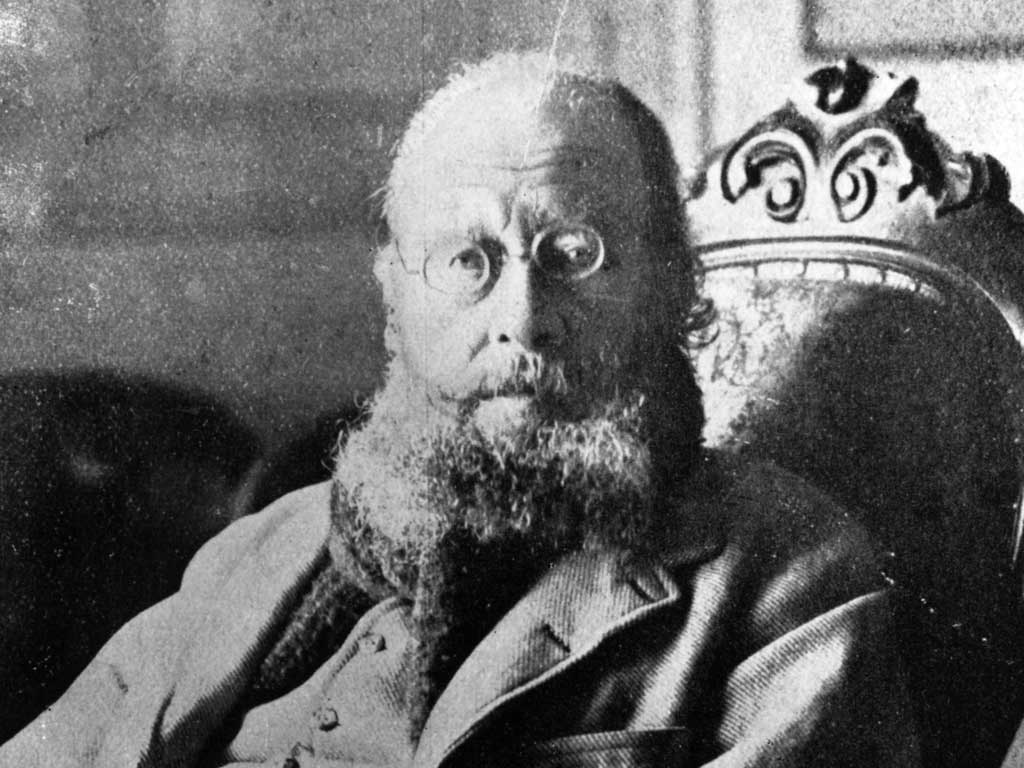

Edward Lear, the poet and master of silliness, was born 200 years ago this week. You might be surprised how many of today's comics are in his debt

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the most interesting things about Edward Lear – interesting, that is, if you're one of those creepy murderers who like to dissect comedy and look inside its wallet to see where it gets its dry-cleaning done – is that nobody, to the best of my knowledge, has ever tried to analyse his work, scour it for Freudian elements and veiled references to the War of the Austrian Succession, or suggest it has Hidden Meaning. I know, because I am one of those creeps who likes to dissect comedy, and I've tried with Lear. However, faced with lines such as "Mr Jones (his name is Handel –/ Handel Jones, Esquire, & Co)/ Dorking fowls delights to send/ Mr Yonghy-Bonghy-Bo!", you simply have to retreat with a slightly quacking nervousness to a safe corner and admit that "The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bo" is no more and no less than what it says it is, namely nonsense.

Edward Lear was born on 12 May 1812 in the village of Highgate, now one of north London's most upmarket areas. The youngest of 21 children, he suffered grand mal seizures and depression from his early teens, something of which he was ashamed (characteristically, he called his bots of depression "the Morbids"). A talented artist (his Illustrations of the Family of the Psittacidae, or Parrot is an extraordinarily beautiful book), he lived much of his life in Italy, deeply attached to his terrible Albanian cook, Georgis, and his cat called Foss, which he loved so much that, when he had a new house built, it was a replica of the previous one so as not to distress Foss. He's well known for popularising the limerick in a less tortuous form than the one into which it later evolved; for writing a poem about himself ("How pleasant to know Mister Lear..."); and for nonsense verse such as the aforesaid Yonghy-Bonghy Bo, "The Dong with the Luminous Nose" and, of course, "The Owl and the Pussycat" (try to not say the next two lines, if you can – it's almost impossible). As well as serious illustrations of parrots, he also drew brilliant grotesques in the naive style that has since become a tradition practised by the likes of James Thurber, Spike Milligan, John Lennon, Vic Reeves and Noel Fielding.

He single-handedly invented "nonsense". Nonsense is an odd thing. Unlike absurdism, which inverts the normal world to make a point, or surrealism, which renders dreams and dream-like states as if they were real, nonsense just is. Readers can find parallels to Lear's own love life, or lack thereof, in some of his work, but they can also, with equal ease, not find parallels.

It's all just nonsense. Runcible spoons and a monkey with lollipop paws, and the hills of the Chankly Bore. You can enjoy the rhythms, or the sonorousness of the words, and you can delight at the imagery. You can be charmed or irritated. It doesn't matter. There is –rather brilliantly in an era when even Ricky Gervais's Flanimals has depths – nothing else there other than what you see.

This is a good thing. Anyone who's ever read the brilliant Aspects Of Alice (subtitled, without a care, Lewis Carroll's Dream Child as Seen Through the Critics' Looking-glasses, 1865-1971) will know just how much meaningless meaning can be imparted to the previously innocuous. Even J R R Tolkien, a man for whom humour was rarely intentional, was forced to write a preface to later editions of The Lord of the Rings explaining that it was not an allegory for the Second World War and Sauron the wizard wasn't Adolf Hitler.

We search endlessly for meaning in art and literature. What do the rhinoceri in Ionesco's Rhinoceros stand for? Is the Red Queen really Cardinal Newman? Was Jonathan Swift satirising 18th-century life in Gulliver's Travels? Well, yes to the last one, but that's not the point. There have always been two kinds of humour; the kind that is about something – Swift, Dickens, Beyond the Fringe, Spitting Image, Yes Minister – and the kind that is about nothing. Into that category I would place The Crazy Gang, Spike Milligan, Morecambe and Wise, Tommy Cooper, Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer, The Mighty Boosh, Harry Hill and The Pirates! in an Adventure with Scientists. All these have references to the world around them, but only in the way that a clown might drive a clown car: because it's funny, not because it's a satire on the automobile industry.

Brian O'Nolan writing as Myles na gCopaleen was often mocking something real in his newspaper column; Brian O'Nolan writing as Flann O'Brien was creating a world in his novels where normality has ridden a bicycle made of sanity once too often and become infected with madness through the saddle.

When you read "The Owl and the Pussycat", you are not being asked to consult a set of footnotes as you go (pace O'Brien's De Selby) which invite you to consider the Owl as the Pope and the Pussycat as Queen Victoria (for whom Lear briefly served as a drawing master). You are being asked to imagine that a bird and cat have fallen in love and decided to (all together now) sail to sea in a beautiful pea-green boat. If you don't find that funny or cute, fair enough. Perhaps you'd be interested in this copy of Animals by Pink Floyd, or some other equally iron-fisted look at the world. Sometimes an emperor has no clothes, just as a Pobble has no toes.

Lear, it has been noted, never resorted to the famous obscenity of later limerick writers. Not only should we be grateful for this (can there be a more horrible pause in the fabric of time than waiting for some red-nosed buffoon to plod their way towards a rhyme for "ducked"?), but it also illustrates the real nature of nonsense. It's not hijackable by sex or politics or anything mundane. Even death is absurd in a way that a mime artist licking a skull under too-bright lighting could never imagine. The fact that the Jumblies – a strange crew of creatures who I've always imagined as the original settlers of the Night Garden, later evolving into Pontipines and Wottingers – went to sea in a sieve is not a comment on the unpreparedness of human beings, it's just funny. They wanted to go to sea, they owned a sieve. That's all.

Lear's humour, never explaining itself, never struggling to fill the available space (I'm not actually here to attack Lewis Carroll, but the next time I have to read his somewhat ickly Sylvie and Bruno books, I would very much like to be paid), and never about anything other than what it is, freed up a whole new direction for humour.

Music hall acts have always known about the power of nonsense, as have the best stand-ups (that is, the ones who don't feel compelled to ask us if we remember our own possessions for two hours) – and, I would argue, almost anyone whose work has lasted over the centuries. Dickens's and Shakespeare's humour survives because the characters in their work, the Malvolios and the Micawbers still exist. Edward Lear's characters, such as they are, resemble nothing and nobody, and yet they are still with us, which in some ways is a more remarkable feat.

There is a cartoon by Lear illustrating the occasion when a stranger accused him of falsifying his own existence, and said that "Edward Lear" was a pseudonym. Lear's riposte was to show the stranger the inside of his hat, in which his name was written. For a moment, you imagine the other man hoping against hope that the name in the hat might be "Ellery Pargeter" or "Alfred, Lord Tennyson", which would mean he'd detected a bad secret at the heart of Lear's entire existence. But it was not to be. Edward Lear's nonsense was written by Edward Lear, and it was complete nonsense, and that is all there is to it. The fact that we still live in a world partially moulded by that nonsense is, in my far from humble opinion, a remarkably good thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments