Christina Patterson: If you don't like capitalism, why not try North Korea?

I'm not sure you could say 'socialism' in North Korea is on its way to being completely 'victorious'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

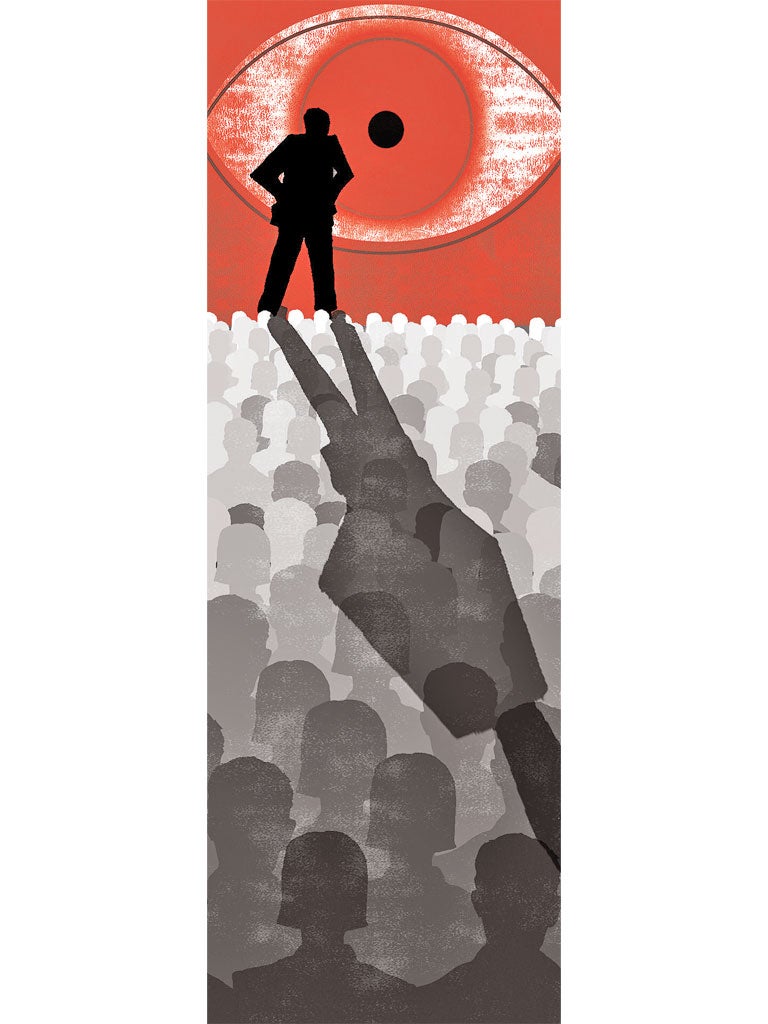

Your support makes all the difference.You've never seen grief like this. You've never seen people throw themselves to the ground, and thrash around, and rub their eyes as if by rubbing them they could wipe away the pain that was exploding out of them, and which they thought would never go away. You've never watched whole audiences in a cinema screaming in despair, or men, in meetings, sobbing like babies. You've never glimpsed a newscaster so choked with sadness that she could hardly say the words she had to say, or heard a news agency report that people feel as if "the sky is falling down".

But that's because you've probably never been to North Korea. You probably haven't, for example, been there on the birthday of the man they call the Great Leader, who died in 1994, but which they still celebrate every year with flowers, and ceremonies and songs. You probably haven't heard a grown-up woman say, to a woman who has been to North Korea, and made a programme about it last year, which won a prize, that the man whose birthday they were celebrating was "immortal". Or heard a man, who happened to be wearing all his medals when the TV cameras turned up, say that it was "thanks to the kindness of the great leader" that North Koreans lived in "civilised homes".

Even if you had been to North Korea, you probably wouldn't have seen that most North Koreans don't, in fact, live in "civilised homes", and that you have, like the woman who made the programme, to drive for hours, on roads that are empty, because there are no private cars, to see one, on a "mechanised, model farm" (but without any signs of anything mechanical) which the cameras are allowed to film. You wouldn't have seen the gulags, where prisoners were burnt, or buried alive. Or heard about the millions so hungry that they tried to eat grass, or the two million so hungry that they died.

You would, instead, have seen the statues, and the posters, and the shrines, to the dead leader who wasn't dead, and to his son, who wasn't then dead, but now is, though it's not yet clear whether he's immortal, too, and you'd have been told about the rainbows that arrived when the son was born, and about the 1,500 books he wrote at university, and about how he was, until he died on Saturday, "the most respected leader in the world". And you might, like the woman who made the programme, have been allowed to see some of the people who were allowed to use computers (which most people in the country aren't) and who were given access not to the internet (because nobody's allowed to have access to the internet) but to a special intranet that gave you all the information you'd ever need.

And it's possible that you might, even though you weren't allowed to take your cameras, or to film anyone who was carrying any food that they might have bought at one, have been able, like the woman in the programme, to go to a private market. At a private market, unlike almost anywhere else in North Korea, except the tables of the leader, who had special foods flown in from around the world, you might see quite a lot of food. At a private market, you might find a way to feel less hungry for a few hours, though you'd still probably only get to eat meat twice a year. But you're not meant to go to private markets. You're meant to get by on your government rations. "In the future," said a government official to the woman who made the programme, "when socialism is completely victorious, the markets will disappear".

I'm not sure if you could say that "socialism" in North Korea is on its way to being "completely victorious". If "socialism" being "victorious" means that a lot of the population get to eat things that aren't grass, and are roughly the same height as their South Korean neighbours, and not at least three inches shorter, then I think it would be quite hard to say that it was. But if "socialism" being "victorious" means that you sing songs about being the happiest people in the world, and smile as if you believe it, and that you cry, and scream, and rub your eyes when your leader dies, even when there aren't any cameras to see you, then maybe it is.

You might, in fact, say that "socialism" in North Korea has been nearer to becoming "victorious" than "socialism" in its current and former allies. You probably couldn't say that it's been more "victorious" in getting food into people's stomachs, but then most "socialist" countries aren't all that good at getting food into people's stomachs. In most "socialist" countries, you have to queue, for hours, for tiny portions of things that don't taste very nice. But you probably could say that it's been more "victorious" in controlling not just what people say, and write, than in other "socialist" countries, where you tend not to be able to say anything that's critical of your government, unless you want to be sent to a gulag, but also what people think.

If you live in a country where most people are hungry, and you get sent to a gulag if you say something that the people in charge don't like, it's probably better to think that this is a good situation, and that you love your leader, than that it's bad, and you don't. If, for example, you live in a country where these things happen, but you don't think it's a good thing, then you might, like Vaclav Havel, who managed to ride a tide of history and change the system in his country, feel that it makes you "morally ill" when you're "used to saying one thing, and thinking another". And it's not much fun to feel "morally ill". Particularly when you're already physically ill, because you're hungry.

The people around the world, in London, and New York, and Italy, and Spain, who have been waving placards saying capitalism has failed, might want to remember that the only alternative to capitalism that has so far been developed hasn't done all that well. It hasn't been all that good for people's stomachs, and it hasn't (but it depends on your point of view) been all that good for their minds. And it certainly hasn't been all that good for people who want to pitch tents on other people's property.

Capitalism is certainly in crisis. It certainly needs some serious work to make sure that gaps between rich and poor in the Western world don't keep getting bigger. It needs some hard thinking on financial services, and specialist manufacturing, and tax. But capitalist democracies have, for all their failings, brought their citizens a standard of living most people in the world can only dream of.

It was, of course, a revolution that led to the "socialist" experiment in Russia, and the one in Cuba, and the one in China, before they let the markets in. Perhaps all those people who want to wipe the slate clean should be just a little bit careful what they wish for.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments