The gathering storm: A look back on middle-class Europe's last carefree Christmas before the onset of World War One

From the following summer, Britain, mainland Europe and a large part of the rest of the world changed for ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wilfred Owen spent a lonely Christmas teaching in Bordeaux. He complained that he had received no Christmas cards from his favourite, former pupils in England.

Raymond Asquith spent Christmas Day with his father, Herbert, at the family home at Easton Gray in Wiltshire, "a typical example of dignified English domestic architecture".

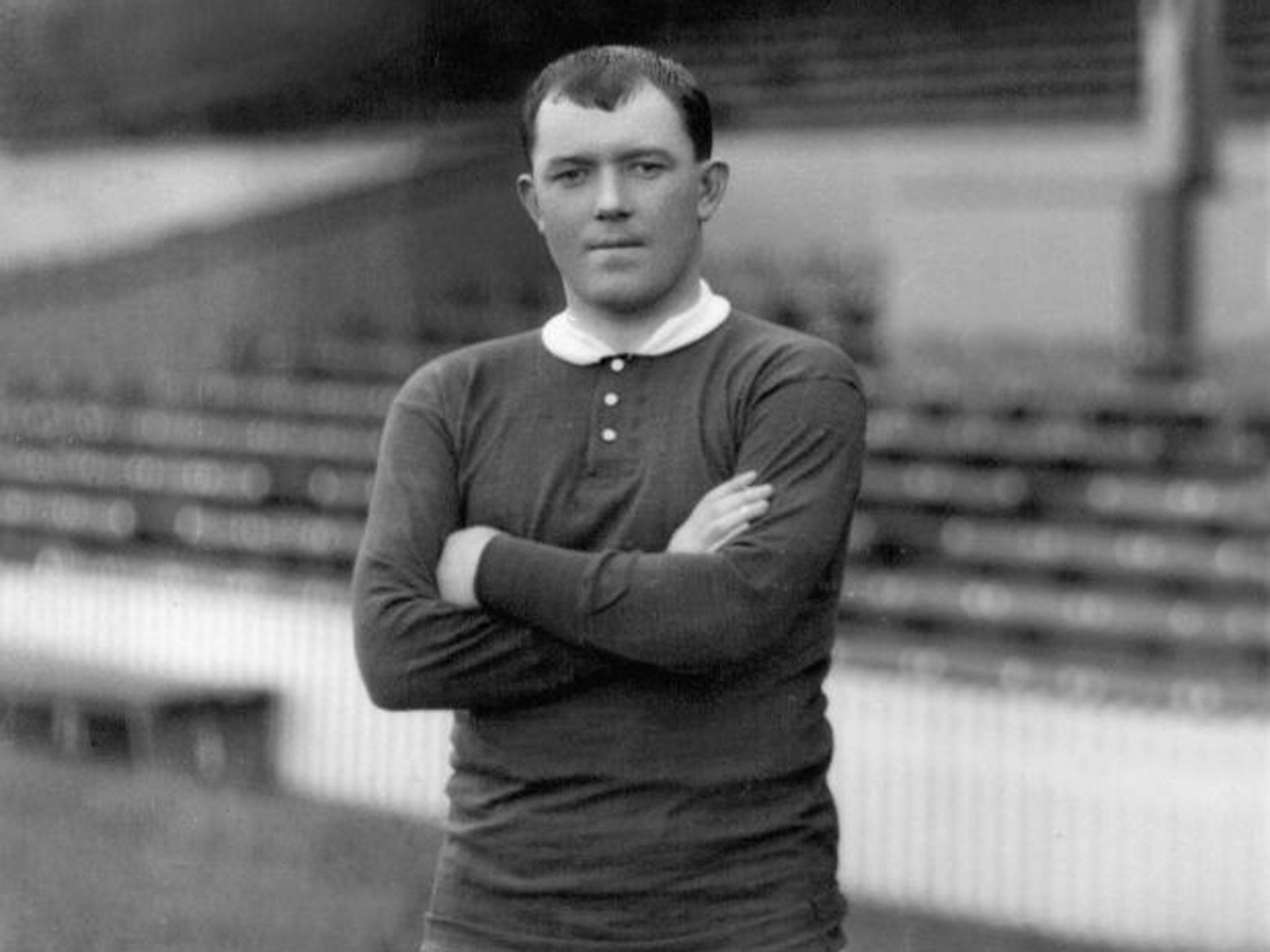

Sandy Turnbull played inside left for Manchester United on both Christmas Day and Boxing Day. Turnbull was a leading player in the first great United team, which was beginning to fall apart. United suffered two defeats by Everton that Christmas, 0-1 and 0-5.

Jack Kipling went to the Christmas shows in London with his famous writer father, Rudyard, and then travelled with him to a chateau in France owned by the American railroad lawyer, Chauncey Mitchell Depew II.

Henri Alban-Fournier was celebrating the success of his first novel, Le Grand Meaulnes. The book had been cheated of the Goncourt prize the previous month but was the best-seller in France that Christmas. Its author may also have taken his football boots down to a muddy field beside the Seine, where he ran one of the first French rugby clubs.

Alfred Lichtenstein did not celebrate Christmas but spent the holiday at home with his wealthy, Jewish family in Berlin, discussing his recent military service and the publication of his doubly prophetic book of poetry, Die Dämmerung (The Dusk).

"Soon there'll come – the signs are fair –

A death-storm from the distant north.

Stink of corpses everywhere,

Mass assassins marching forth."

Christmas 1913 was the last Noel: the last Christmas before the world plunged into its first global and industrial war. From the following summer, Britain, mainland Europe and a large part of the rest of the world changed for ever.

The 1914-18 war did not create the modern world, but it fast-forwarded many processes that had already begun, from the breaking of empires to the emancipation of women. The real transformation – our sense that the 1920s are the beginning of a different world – is based on something more intangible. It is summed up in Philip Larkin's line: "Never such innocence again".

Within five years, all the young men listed above were dead. So were 10,000,000 other combatants and 7,000,000 civilians. Our six represent not just the "doomed youth" of Christmas 1913 but, in their different ways, the golden hopes of the first decade of the 20th century.

Wilfred Owen was the son of a station master and among the first generation of young British men from modest backgrounds to aspire to go to university. He was killed seven days before the end of the war on 4 November 1918, aged 25. His poetry, including the words "doomed youth", came to define the Great War – and all wars – for generations of Britons.

Raymond Asquith was the oldest son of the Prime Minister, a barrister who had just started a career in politics. His friend John Buchan described him as one of those people "whose brilliance in boyhood and early manhood dazzles their contemporaries and becomes a legend". He was killed on 15 September 1916 during the battle of the Somme. He was 27.

Sandy Turnbull, from Hurlford in Scotland, was a turbulent star of the first great period of professional football in Britain. He scored the only goal in Manchester United's first FA Cup victory, in 1909, and the first goal ever scored at Old Trafford in 1910. He was embroiled in illegal payments, a players' strike and match-fixing. He was killed on 3 May 1917 during the Battle of Arras.

Jack Kipling was the apple of his father's eye. That did not stop Rudyard, the poetic voice of Empire, pulling strings to get his teenage son into the front-line trenches. Jack was last seen staggering with half his face blown away during the Battle of Loos on 27 September 1915. His body was never found. He had celebrated his 18th birthday the previous month.

Henri Alban-Fournier, better known by his pen name Alain-Fournier, has come to represent for the French – and not just the French – the lost world of pre-1914. His only novel, Le Grand Meaulnes, is a classic of the thwarted and idealised passion of youth. As a reserve lieutenant, he was mobilised on the first day of the war in August 1914 and killed the next month. He was 27.

Alfred Lichtenstein, expressionist poet, reluctant lawyer and son of a factory-owning family in Berlin, was also mobilised in August 1914. He was killed in (by later standards) a small French-German engagement during the Battle of the Somme, on 25 September 1914, three days after Alain-Fournier. He was 25.

We think of our grandparents and great-grandparents paddling downstream in boaters and long dresses, unaware that Niagara was around the next bend. In truth, the first years of the last century were not like that.

They were littered with social unrest, military scares, warnings of the hubris of industrial mankind and examples of the fragile hypocrisies of imperial democracies and semi-democracies.

There was a war in the Balkans; there was a threat of civil war in Ireland (never more so than at Christmas 1913). In Britain, there was an increasingly violent campaign for women's suffrage and an increasingly vicious, government suppression of the suffragettes. There was the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, a harbinger, if ever there was one, of the fateful arrogance of modern mankind.

There was the Agadir incident in 1911, when France and Germany almost went to war over French expansion in North Africa. There was a surge in military spending, which in Britain took the form of a naval arms race with Germany.

Above all there was a sense that an explosion of new technology and unevenly distributed wealth was transforming the old order in ways that were impossible to control or predict. Does that sound familiar?

The French writer Charles Péguy (killed in the battle of the Marne on 5 September 1914) said in 1913: "The world has changed more in the last 30 years than in all the time since Jesus Christ."

By the end of the year, diplomatic relations between Britain and Germany and France and Germany had eased. The Balkan war was over.

The Liberal Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, said just after Christmas 1913: "Our relations with Germany are infinitely more friendly now than they have been for years. Sanity has now been more or less restored on both sides of the North Sea."

The Economist, self-assured then as now, told its readers to go home and party. "There is no reason why the inhabitants of this prosperous little kingdom should not enjoy a merry Christmas."

The Daily Graphic, ancestor of the Daily Mirror, was more prescient. "Wherever we look we see the grim apparatus of war … clogging the wheels of industry and squandering the fruits of peace."

This was a lone voice. Some feared a European war. Few imagined that "progress" – not just modern weapons but railways, aeroplanes, canned food, industrial production, powerful economies – were about to mutate into the cancer of the most destructive war the world had ever known.

It had been a beautiful year of fine weather and bumper harvests, which stretched into an Indian summer. In Britain, the roses were still in bloom.

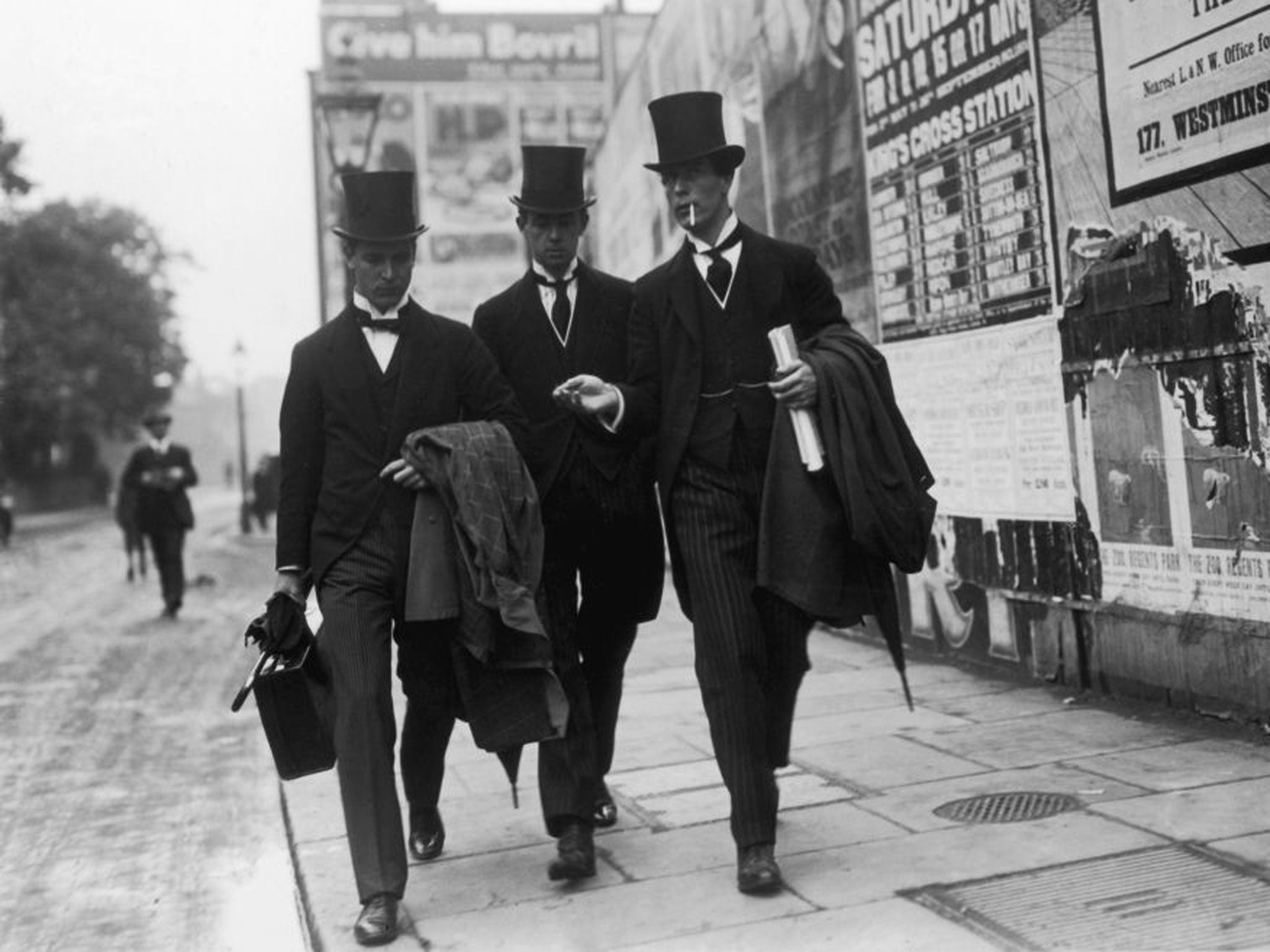

On 26 December 1913, The Manchester Guardian's London correspondent wrote: "Christmas Eve was perfect, at any rate for the comfortably dressed, and the West End shopping streets were happy places. Everyone was carrying parcels and none of them (one takes it) were carrying things for themselves, so for a moment things took in the look of an ideal world."

A London bus strike had been averted. A postal strike had been abandoned at the last moment. Turkeys were in short supply because of industrial unrest in Ireland. Prices were up tuppence a pound (2p a kilo) on the previous year.

"This is said to have been the most prosperous Christmas week that London shopkeepers have known for many years," the Guardian said. "Money has been very plentiful." More than 50 extra trains were run out of Euston "crowded to overflowing".

In Manchester, there were "immense crowds in the shopping streets". Popular presents were a "cosy gents dressing gown" or a Chantilly lace scarf "for the ladies", each at 21s 9d (about £1.10), or a silver matchbox for 4s 3d (21p). Servants could be given a "useful" present such as an apron at 1s 11d (10p). Children of the rich might ask for a £15 13s 3d toy car, four feet long.

The year had begun to the syncopated beat of ragtime and ended to the raunchy sound, and sight, of the tango.

In France the most popular Christmas toy for girls was the mechanical, dancing tango doll, price 10 francs. "A lady correspondent" in The Observer wrote from Paris: "Oysters, aspics of pheasants, foie gras … were served at most of the smart suppers. In the humbler restaurants … black puddings and Portuguese oysters … were as joyfully attacked at a few francs a head. The tango was danced on every waxed floor of the capital on this most boisterous of Christmas Eves."

The British poet laureate, Robert Bridges, published a Christmas poem in The Times, which has since become a sentimental classic. It began with a line in Latin "Pax hominibus bonae voluntatis" – "peace to all men of goodwill".

Almost all Christmas and New Year commentary in the European press was optimistic, even enthusiastic, about the future. An Observer correspondent in Paris, reviewing the end-of-year coverage of French and German newspapers, wrote: "The relations of the [French and German] governments have been excellent and continuous …. A blue sky is showing above the rose of the dawn of 1914."

As if in warning, the balmy weather plunged into a big freeze just before the New Year.

No, the modern world did not start with the 1914-18 war. Movies, telephones and aeroplanes already existed. Picasso and Braque were already at work in Paris. James Joyce sent the draft of Dubliners to Ezra Pound in December 1913.

In that same month, Marcel Duchamp created – or discovered – his first piece of "ready-made" art, a bicycle wheel. Just before Christmas 1913, the first industrial assembly line, making Model T Fords, was started in Detroit. Charlie Chaplin signed his first contract in Hollywood. Lenin was plotting in Krakow; Stalin was in exile in Siberia.

In his marvellous book 1913: The World Before the Great War (Bodley Head, £25), the young historian Charles Emmerson points out that Europe before the Great War was, in some respects, more open and united than it is now. You did not need a passport to go from Dover to Calais in 1913.

The European royal and upper classes were one big family. The middle classes had the same tastes. The working classes – or some of their leaders – dreamed of a Europe-wide revolution. A Labour Party motion in December 1913 called for a general strike "in any country affected by the outbreak of a European war".

The pre-war period, Emmerson says, was not just a sleepwalk to Armageddon, but a period of "possibility, not predestination … of unprecedented globalisation, rich in encounters, interconnections and ideas".

What the war changed most, as Philip Larkin suggested in his great poem "MCMXIV", written in 1964 for the half-centenary of the war, was the social deference born of ages; a blind trust in authority; a belief that everything was most likely to advance towards a better world. "Never such innocence again."

Much of that deference and trust was best ditched (though not at the cost of 17,000,000 lives). The war fast-forwarded history; it also set the world back. International trade took 60 years to return to the level of 1913. The war destroyed a ramshackle international system and unleashed forces of ultra-nationalism which led to a second, even more destructive war in two decades.

There are "striking and unsettling parallels", Emmerson says, with the "geopolitics of the world today". He does not go there, but try casting today's China as the impatient, rising Germany of 1913; or today's America as the already declining Britain of that time; or today's well-meaning, stumbling European Union as a fracturing Austria-Hungary whose collapse unleashed vicious, nationalist hatreds and rivalries .

We have abandoned innocence. Are we any better in 2013, than we were in 1913, at distinguishing between the "rose of the dawn" and "mass assassins marching forth"?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments