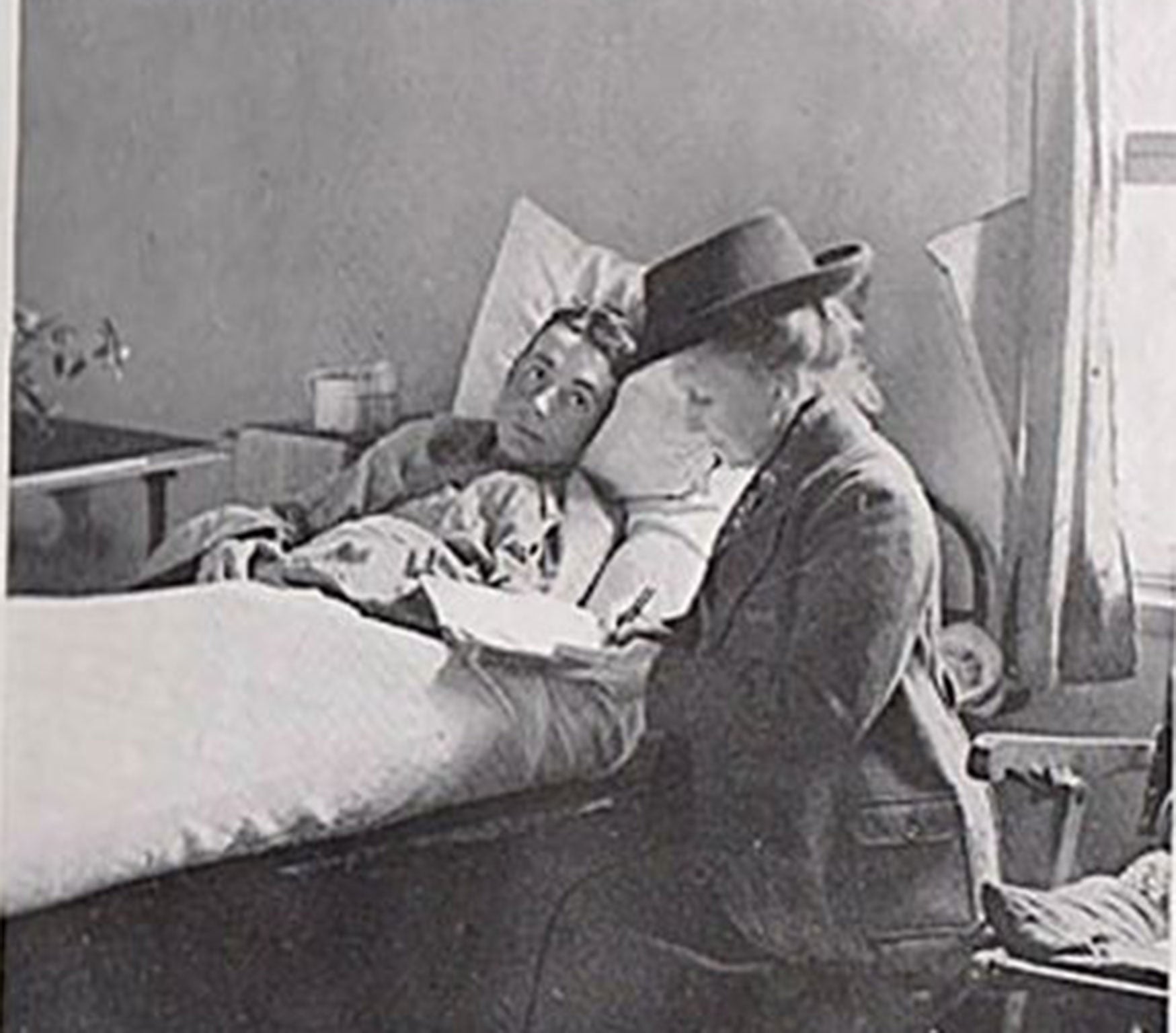

A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: The soldier and the letter-writer - a lady with a notepad who gave comfort to the dying

May Bradford provided a priceless service, writing letters to loved ones on behalf of injured soldiers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For several days early in 1917, May Bradford sat beside Corporal George Pendlebury in a British field hospital in France, comforting him and writing to his family as he edged towards death. By the time he succumbed to pneumonia, the young soldier believed she was not his nurse, but his mother.

Unlike her colleagues, she rarely dispensed drugs to relieve the agony of injuries inflicted on the Western Front. Instead, her medication was administering the written word and empathy in the gruelling surroundings of No 26 General Hospital, near Etaples.

A volunteer nurse for the British Red Cross, she followed her surgeon husband, Sir John Bradford, to northern France at the outbreak of the war and spent the duration of the conflict performing the remarkable yet unsung role of “hospital letter writer” for injured soldiers either too unwell or too illiterate to communicate with family members scattered across the globe.

Lady Bradford was, by any standards, prolific. By the end of the war, she had written no fewer than 25,000 letters and notes – an average of about a dozen a day – on behalf of her charges at No 26 (which was the real-life basis for the BBC1 drama series, The Crimson Field). In so doing, Lady Bradford filled an information vacuum. Her Red Cross letters added precious details of injuries and condition to loved ones who otherwise received only a terse War Office note informing them that their husband, brother or son had been wounded.

No less importantly, she also became a form of professional confidante and conduit for the love, sorrow, horror and longing transmitted between soldiers and those at home.

A member of the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), as the Red Cross volunteers were known, the nurse-cum-scribe was part of a force that became the backbone of military nursing during the war. Some 38,000 VADs were deployed as assistant nurses, ambulance drivers and cooks, serving as far afield as Mesopotamia, Gallipoli and the Eastern Front.

Dressed in a dark suit topped with a formal hat, Lady Bradford eschewed the uniform of her fellow VADs for something akin to her Sunday best and saw her role less as matronly than maternal.

Summing up her job after the war, she wrote: “The duties of a letter writer were very varied. She must ask many questions – she must never be in a hurry; the men liked to pour out their troubles and anxieties. I was not in uniform, and this absence of uniform introduced a personal touch that must necessarily be absent in any relationship impressed by discipline.”

Recalling her care of Cpl Pendlebury, she wrote: “I would tell these men that I was there to mother them until they return to their homes.

“I said this to an Australian and he quickly replied ‘Mother, give me my tea’. I gave it to him, and then wrote to his mother in Australia. The next day he called me as I entered the ward, ‘Mother, tuck me up’. I did so. ‘You do tuck up well,’ said he, ‘just like mother’.” The soldier, who had lost a leg when he was hit by a trench mortar, slipped away to pneumonia, before dying on 1 March 1917. Lady Bradford added: “From calling me his hospital mother he thought I was his own dear mother, and he died thinking she was by his side.”

Unlike other correspondents writing from the front, Lady Bradford, who became known to her charges in the hospital as “Tommy’s little Mother”, was allowed to seal her letters and thus avoid the military censor. The intimacy of the relationship between letter-writing nurse and the injured was lost neither on Lady Bradford nor on those to whom she was writing.

One mother, concerned that her son was falling for the charms of his warm-hearted carer, wrote to his matron: “Please let me know who May Bradford is, my son is very susceptible.” It was only when she was assured that the writer was middle-aged and happily married that such anxieties abated.

Writing for men whose education and literacy were often limited, this Florence Nightingale of the pen, who frequently received letters addressed to “Major Bradford”, was also not afraid of educating her patients on how to treat women.

She recalled: “To one man I said, ‘Shall I begin the letter with my dear wife?’ He quietly answered, ‘That sounds fine, but she’ll be wondering I never said that before’.”

From writing on behalf of a soldier to his brother in India in the hope that “he may leave me a lot of money” to reading to another a letter from his mother expressing a desire to visit him “if I need not go into the trenches”, Lady Bradford was privy to nearly every emotion and need in the hospital. Her role brought with it moments of levity, such as the reaction of one Scottish soldier who, when presented with a Christmas card by the nurse with a picture of dogs, rejected it, saying: “My mither canna thole [abide] dogs.”

But the grim consequences of war were never far away. She later recalled: “One day a youth was brought in with both eyes shot away. After all his messages to his wife and children had been written down, he put his hand to try and find mine. ‘Sister,’ he said, ‘is it a fine day, and are the birds singing?’

“I pictured it all to him. ‘Well,’ he answered, ‘I have much to live for still’.”

Tomorrow: A Poet and a painter pine for home

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments