A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: The sinking of the ‘Lusitania’ - the torpedo that changed the course of war

Germany said the British liner was a legitimate target. But the U-boat attack that killed 1,198 civilians caused such outrage that it sounded the death knell for US neutrality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Trepidation hid in the hearts of passengers and crew as tug boats manoeuvred the RMS Lusitania, the pride of the Cunard Line, from Manhattan’s Pier 54 into New York harbour for the start of its voyage to Liverpool on 1 May 1915. Germany had declared the waters around the British Isles an “exclusion zone”, where any vessel of Britain and its allies would run the gauntlet of German submarines.

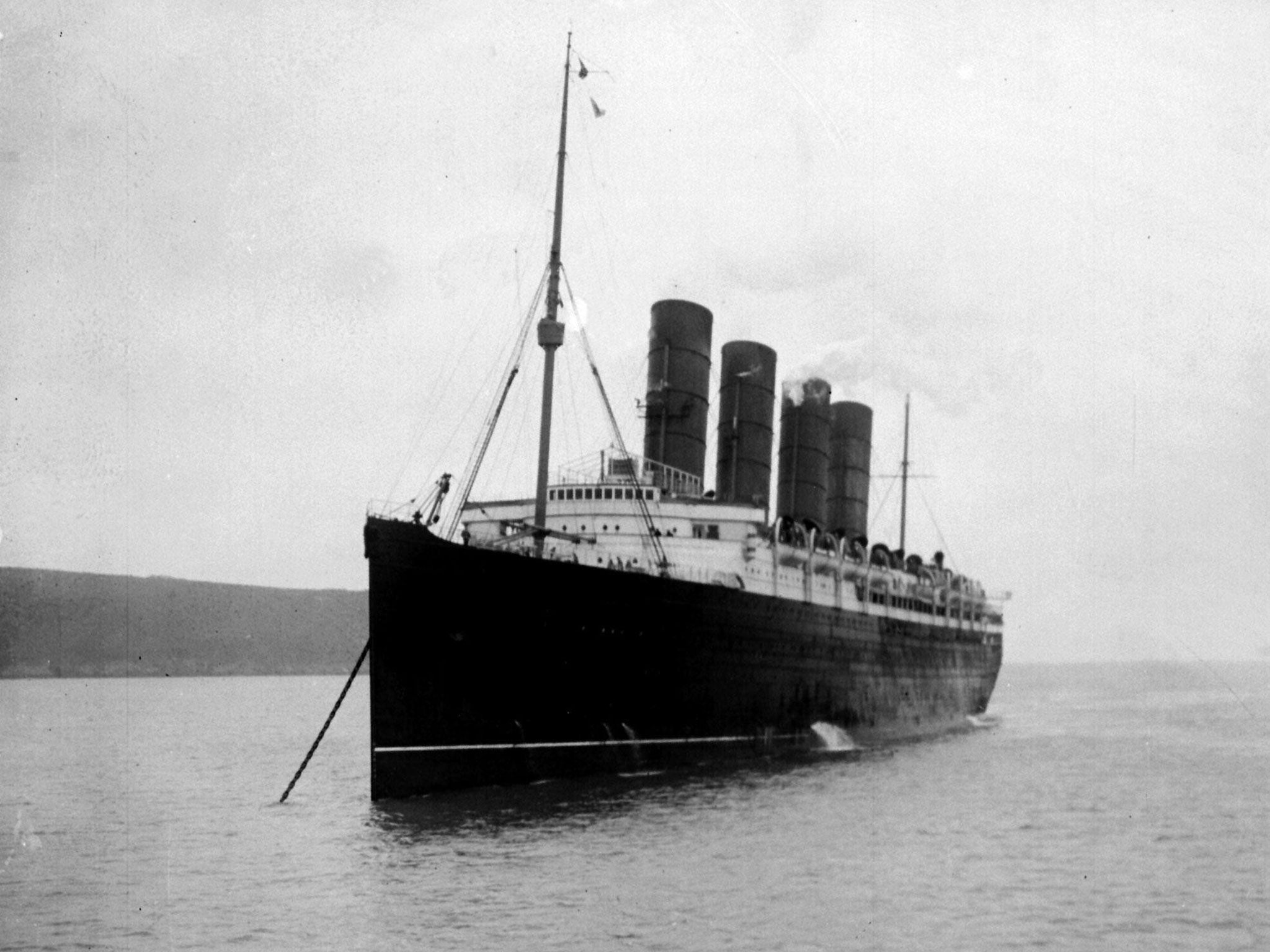

Only days before, the Imperial German embassy in Washington had placed advertisements in US newspapers warning that vessels flying the flags of its enemies were “liable to destruction” if they dared navigate the zone. Yet this particular British liner was teeming on departure. Even in wartime, people persuaded themselves, Germany surely wouldn’t dare sink a ship as grand as the Lusitania, with its famous foursome of tall funnels and its lavish first class. Besides, its vaunted speed meant it could outrun any of the Kaiser’s U-boats.

One week later, the Lusitania slipped to a watery grave off the southern coast of Ireland, sunk by a single torpedo from submarine U-20 under the command of Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger. Lost with it were the lives of 1,198 of the 1,959 on board, among them 139 Americans. The clock on the declaration of war on Germany by the United States had been set ticking, though the hour did not come until April 1917.

Daybreak on 7 May revealed heavy fog and Captain William Turner signalled the Lusitania’s engineers to slow to 15 knots, a decision that alarmed the more aware passengers on board. Then the sun broke through, speed was increased, and easy sailing on flat seas was promised. But the improved conditions meant something else: when, early that afternoon, the U-20 surfaced, the Lusitania was clearly visible steaming eastwards. The ship adjusted course, which promised to take it beyond Schwieger’s reach; but then it turned again. The Lusitania started to sail directly towards the U-boat – and its own destruction.

A lookout spotted the trail of bubbles zipping towards the Lusitania’s starboard side but it was too late. A first explosion, which came with impact, was followed swiftly by a second, larger one. The double detonation was later to cause controversy. The liner, though the British public was slow to learn it, had been carrying cartridges in its hold, for the war effort – a fact that Germany would attempt to use to justify the attack. But had they been the source of the second explosion? Or was it in fact coal dust in the ship’s near-empty bunkers?

Not that it mattered to those on board. Evacuation, once ordered by Captain Turner, was chaotic. Electricity failed, plunging interior decks and cabins into darkness. Some anti-flood safety doors swung shut, trapping those behind them. The sudden and severe listing of the ship made the loading and lowering of its lifeboats perilous or impossible. Of those who survived, many were floating in the sea in lifejackets or grabbing pieces of wreckage.

It had taken just 18 minutes for the majestic liner to succumb to the waves. There were reports of one man clinging to a corpse, another falling down a funnel only to be ejected by another explosion. One lifeboat was loaded with only three passengers. A woman gave birth in the water.

“There was no acute feeling of fear whilst one was floating in the water,” the future Viscountess Rhondda wrote in a memoir, This Was My World (Macmillan, 1933). “I can remember feeling thankful that I had not been drowned underneath, but had reached the surface safely, and thinking that even if the worst happened there could be nothing unbearable to go through now that my head was above the water. The life-belt held one up in a comfortable sitting position, with one’s head lying rather back, as if one were in a hammock.

“At moments I wondered whether the whole thing was perhaps a nightmare from which I would wake, and once, half laughing, I think – I wondered, looking round on the sun and pale blue sky and calm sea, whether I had reached Heaven without knowing it – and devoutly hoped I hadn’t.”

Anger, diplomatic and popular, came quickly on both sides of the Atlantic. In England, riots erupted. While some German newspapers celebrated – “An Extraordinary Victory”, trumpeted the Frankfurter Zeitung on 8 May – British and American headline writers were unified in their disgust.

“British and American Babies Murdered by the Kaiser,” lamented the Daily Mail. A more restrained New York Times declared: “Few of Liner’s 1,273 Victims Found; 120 Americans Dead; Sinking of the Lusitania is Defended by Germany; President Sees Need of Firm and Deliberate Action.”

Exactly how Woodrow Wilson would respond was of urgent interest, as relayed in this dispatch to the Daily Mail. “Like a prairie fire indignation and the bitterest resentment is sweeping today over the American continent. The only question is: Will this universal feeling of horror and mingled grief for the innocent victims of the greatest crime in history overwhelm the Government and force it into a declaration of war?”

But Wilson maintained his position that the US should stay neutral. “The example of America must be a special example,” he said in Philadelphia three days later. “The example of America must be the example not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world and strife is not. There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.”

But the sinking of the Lusitania had already lit a fuse. It had brought Europe’s raging war home to many ordinary Americans and helped them conclude that Germany was the enemy of peace.

By the spring of 1917, more US shipping assets had been struck by German munitions, and on 2 April Wilson finally went to Congress asking for permission to join the war against the Kaiser; permission that was swiftly granted.

Tomorrow: The poet’s battle cry

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments