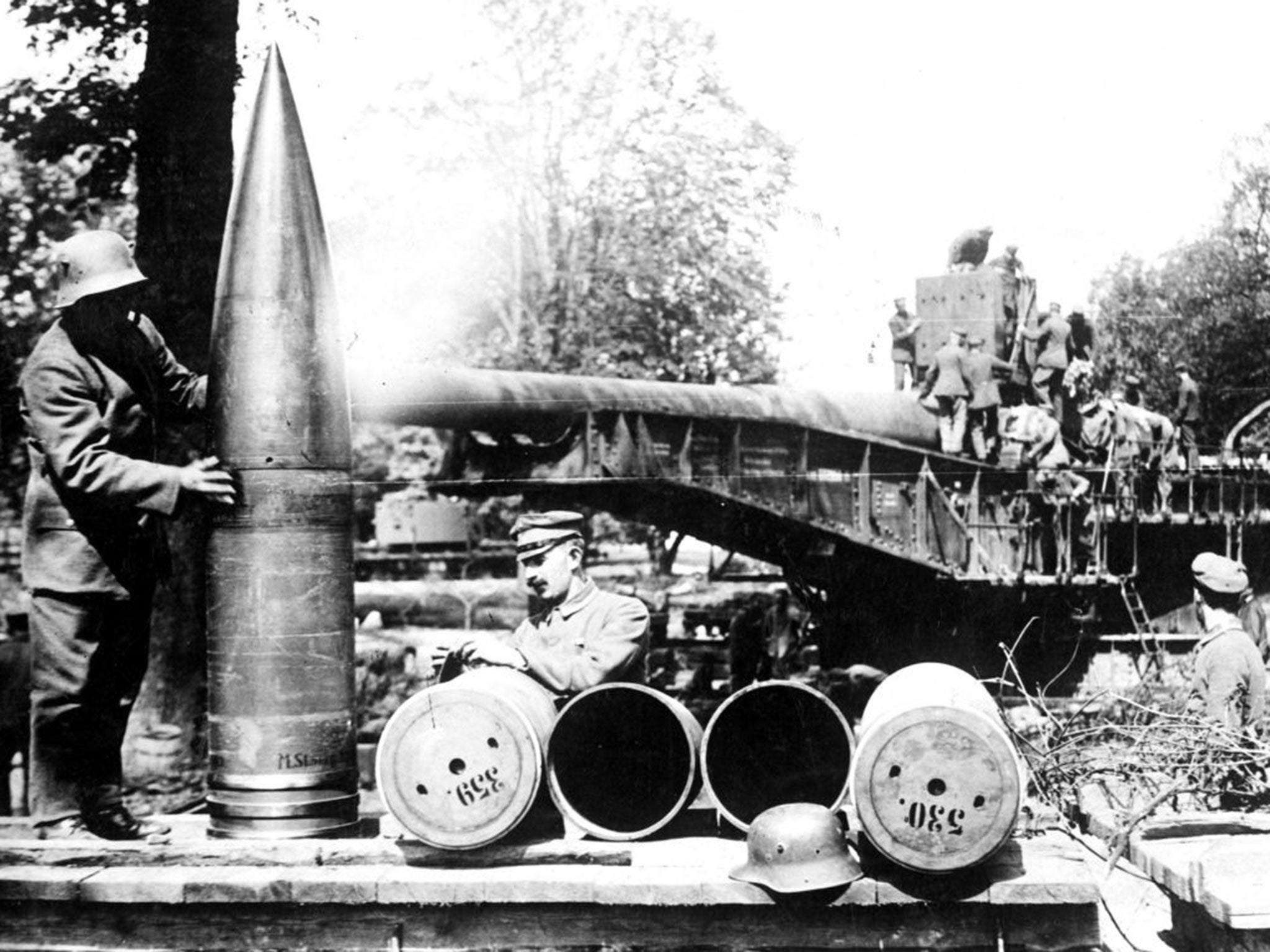

A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: Ordeal by shellfire - a giant gun rains death on Parisians from 80 miles away

A shock artillery attack on the French capital marked the start of an offensive that nearly broke the Allies

At 7.18am on 21 March 1918, a German shell landed on the Quai de la Seine in central Paris. Similar shells continued to explode in the French capital at 15-minute intervals. They resumed sporadically the next day and the next.

Over the next five months, there were 183 explosions in the city, never more than 20 in one day. The damage was relatively small but 250 Parisians were killed.

At first, the effect on nerves, after almost four years of mostly distant warfare, was devastating. The front line was 80 miles away. Surely these could not be artillery shells. They must be bombs dropped from invisible, high-flying aircraft or Zeppelins, or acts of sabotage.

The American ambassador, William Graves Sharp, said it was “as though some strange visitation from the planet Mars, bringing death in its pathway, had suddenly intruded upon the streets of the city… [The shells] simply dropped from space like some hugh meteorite.”

Ambassador Sharp’s metaphor was more accurate than he knew. The 8.5in shells fired by the “Paris Gun” were the first man-made objects to penetrate the stratosphere. The immense naval gun, manned by 80 German sailors, launched 15lb of TNT 25 miles into the sky from Coucy forest, behind the German lines in Picardy. The shells then descended, almost vertically and silently, on to the civilians of Paris.

The date of this display of technical prowess and state terrorism was not chosen at random. On the same day, 21 March, 6,000 smaller German guns and mortars launched a five-hour barrage of high-explosives and gas on British troops in northern France.

Since the autumn of 1914, the fighting on the Western Front had become a form of siege warfare on a previously unimagined scale. The German army had defended 450 miles of trenches between the North Sea and Switzerland. Now, for the first time since Verdun in February 1916, the Germans attacked.

The Paris Gun was symbolic. It was the turn of the besiegers to be besieged. Fifty German divisions advanced through thick, freezing fog and overran the partly finished British defences. More than 21,000 British soldiers were captured in the first 24 hours, including eight battalion commanders, one of the most calamitous days in Britain’s military history.

This was the “Kaiser’s battle”, or Operation Michael, the opening of a three-pronged German offensive: a last, desperate gamble to win the war before the limitless resources of the United States could be mobilised.

With the collapse of Russia and the Eastern Front in December 1917, the Germans had a small numerical advantage in the west for the first time. Over a million men and 3,000 guns had been moved from the east.

The German commander, General Erich Ludendorff, decided that the first and largest blow should fall on the British. He believed that Field Marshal Douglas Haig’s army was demoralised after the misery of Passchendaele the previous year (he was partly right) and hungry and ill-equipped because of the German U-boat blockade (he was completely wrong).

The Germans attacked on a broad front from Arras to Saint-Quentin. With more than a million men engaged on both sides, 21 March 1918 was the biggest single day’s fighting in the war.

Near Arras, the British line held. In the southern part of the battlefield, the Germans broke through.

“This was no longer the enthusiastic, band-of-brothers British army of 1916,” says Martin Middlebrook, author of The Kaiser’s Battle, the classic book on the fighting of March 1918. “This was a conscript army, in other words these were the men who had not volunteered in 1914-15. Many of them had already been through the misery of Passchendaele and Cambrai in 1917. If it had not been for the fog, things might have been different. But many of the British defenders, holding redoubts or strong points rather than continuous trench lines, found themselves cut off by the German advance. Some fought bravely. Others surrendered in droves.”

Lieutenant W D Scott, of the 6th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry, recalled 60 years later in an interview for Middlebrook’s book: “The first I knew that the Germans had attacked at all was when I went around the traverse of our trench and walked into this horrible little German with thick glasses on. It was the first German I had ever seen. He put his bayonet at the centre of my stomach and said: “Kamerad, yes or no? I said: ‘Yes’.”

The defeat threatened to turn into a rout as the Germans rolled in a few days over the devastated old battlefields of the Somme, “captured” by the British in four months of bitter fighting in 1916.

The German plan was to separate the British and French armies and then drive the British back towards the sea (echoes of May 1940).

At an Allied conference at Doullens on 26 March, Haig agreed to place himself under the supreme control of the French commander-in-chief, Ferdinand Foch. In return, some French divisions were sent to the British front.

Two more German blows fell – on 9 April against the British in the Lys valley south of Ypres on the French-Belgian borders and on 27 May against the French in the Aisne.

As on the Somme, most of the territory bloodily won in 1917 by the British around Ypres, and by the French near the Chemin des Dames, had to be surrendered in a couple of days. Paris seemed threatened at one point in June, as it had been in September 1914.

Were the Germans going to win the war before the Americans arrived en masse?

How close they came is disputed. Haig was sufficiently alarmed by the German advances towards the Channel in the north to issue a celebrated appeal (from the comfort of his château) on 11 April: “Every position must be held to the last man. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight to the end.”

After the early calamities, the British Army recovered.

The stop-start German advance through the Somme was halted in a night-time battle in and around the town of Villers-Bretonneux, just east of Amiens, on 24-25 April.

The counter-attack included British troops but the real damage to the Germans was inflicted by Australians, some of whom had previously fought at Gallipoli in 1915 and in the 1916 battles of the Somme. The fighting also included the first tank-vs-tank battle in history.

The other offensives against the British in the north and the French (backed by the Americans) in the south, were also blocked after substantial German gains.

Just like the British on the Somme in 1916 or the French at Chemin des Dames in 1917, the German attackers suffered terrible losses but were never able to turn local success into a strategic breakthrough. Ludendorff’s gamble had failed.

The titanic, savage struggles of early 1918 have not been pounded into popular memory in the same way as earlier battles. And yet they led directly to the great Allied offensives that summer which finally won the war.

As the Allies advanced, the Paris Gun was dismantled, taken back to Germany and destroyed. After the initial panic, Parisians had learnt to treat the gun with the same resigned disdain that they used for other inconveniences of urban living.

The gun’s military impact was negligible but the notion of long-distance bombardment – supposedly banned in the 1920s – was taken up by the Nazis in the 1930s. The super-gun’s spiritual, if not technical, descendants were the V1 and V2 rockets which attacked Britain in 1944-45.

Tomorrow: Britain’s first black officer dies

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments