Dr Livingstone's Zambezi expedition would have failed without the intervention of an overlooked African king

New academic paper claims Scottish missionary was 'entirely dependent' on the 19-year-old ruler of the Kololo people

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

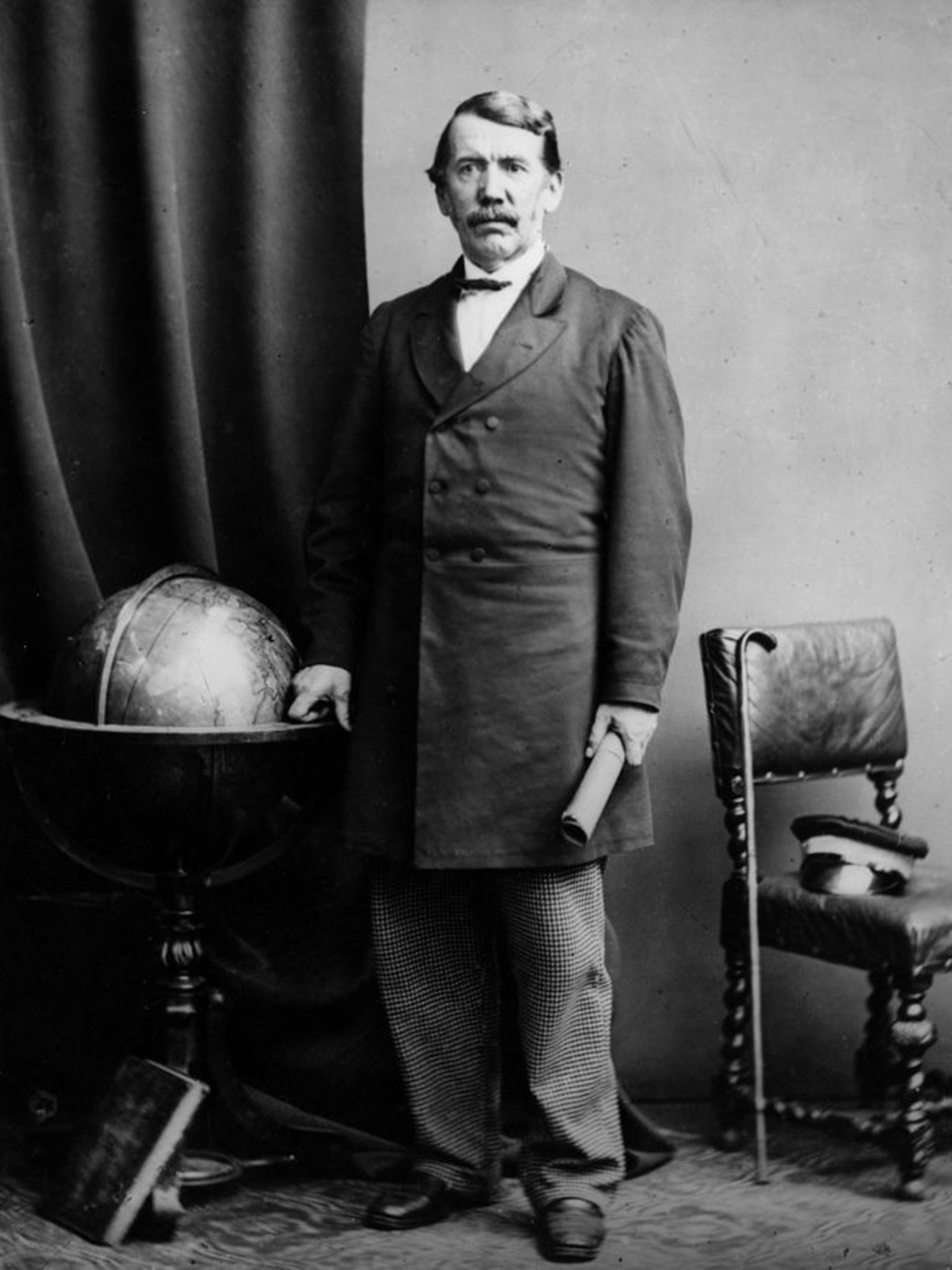

Your support makes all the difference.When explorer David Livingstone returned from a three-year journey across Africa through lands previously uncharted by Europeans, he was greeted as a national hero.

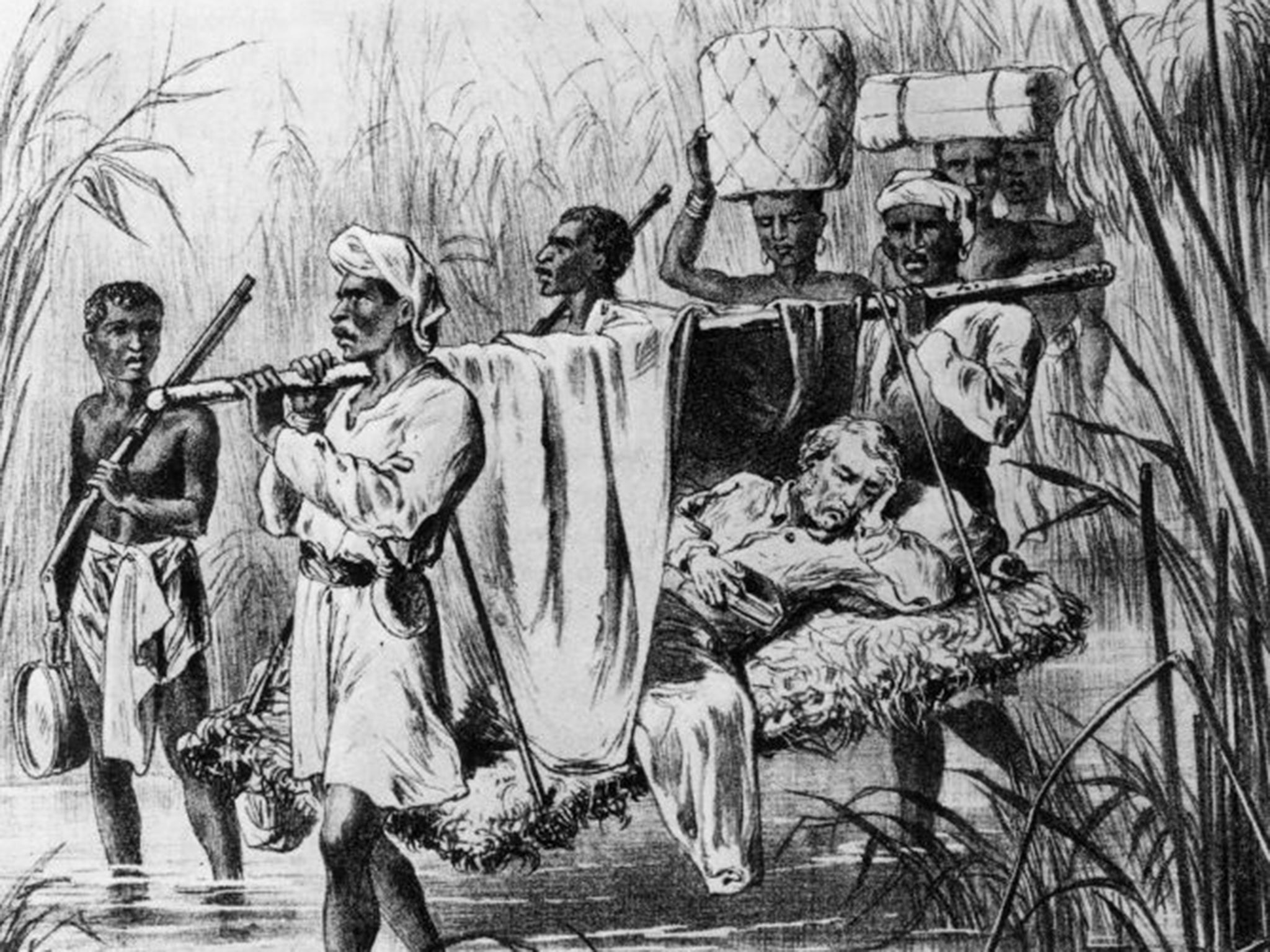

But the Zambezi expedition –during which Livingstone named Victoria Falls after the then queen – would have failed but for the intervention of a 19-year-old African king, according to a new academic paper.

While Sekeletu, the newly appointed monarch of the Kololo people, was later written out of what became a British morality tale of a resourceful, intrepid and pious explorer triumphing against the odds in deepest Africa, in reality Livingstone became "entirely dependent on Sekeletu's generosity" during the trip after his "pitifully inadequate" supplies of "beads, clothes and cloth" ran out.

Historian Walima Kalusa, of Zambia University in Lusaka, said that the young king's reasons for supporting Livingstone's mission were "far from compatible" with the Scottish missionary's hopes to spread Christianity, undermine "the alleged despotic power of African rulers", and open up the area to traders.

"Surprisingly, scholars of the exploits of the missionary explorer in Africa have overlooked the significant role Sekeletu played in the drama of the transcontinental journey that catapulted David Livingstone from obscurity to international stardom," Dr Kalusa, writes in the Journal of African Cultural Studies.

"This scholarly neglect has obscured the motives and meanings the Kololo monarch attached to the expedition. In [Livingstone's] words, the African ruler and his people were as eager as he was to establish a trade route in order to acquire modern goods such as clothes, guns and wagons that would transform them into civilised men."

At the time, Sekeletu, who was rumoured to be illegitimate and the half-brother of a woman who had abdicated from the throne, was struggling to assert his authority in a highly militaristic state that valued valour in battle – which he had not proven because of his age – above royal blood. Fighting well was also the main means by which a man could acquire cattle and wives in the polygamous society. Sekeletu had no cattle when he became king, meaning that he had few means of dispensing patronage to supporters.

"Livingstone was convinced that the Kololo king supported the exploration because he seemed to embrace the explorer's 'civilising mission', the fulfilment of which depended on creating a trade route that would bring British colonists and goods into the heart of Africa," Dr Kalusa writes.

"But … [while Livingstone] saw the expedition and British goods as instruments for propagating Western civilisation in Africa, [Sekeletu] perceived in them an opportunity to reverse the socio-economic and political plight thrust upon him by the workings of his society.

"Rather than enhance social relations and the values of British industrial capitalism, as Livingstone hoped, Sekeletu deployed modern goods to consolidate pre-existing relations and to oil the wheels of political patronage."

Sekeletu saw a chance to shore up his power by opening new trade links. And, "contrary to David Livingstone's expectations", he did so without discarding Kololo customs, retaining "polygamy, beer consumption [and] other local cultural practices".

Sekeletu stayed in power until the 1870s, but then contracted leprosy, which Livingstone attributed to the king's "mental anxiety". Faith in him as a leader waned, and his once powerful kingdom gradually diminished until it was absorbed by the Kololo's long-standing rivals, the Lozi.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments