5 News's Andy Bell retraces his grandfather's steps on the First World War battlefields

Andy Bell only knows his grandfather from the compelling diary he kept during the war. But when he returned to the killing fields where Edwin Vaughan suffered so much, his ancestor came to life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We do not have any memory of my grandfather. He died when my mother was two years old. We have some letters, some photographs and the diary.

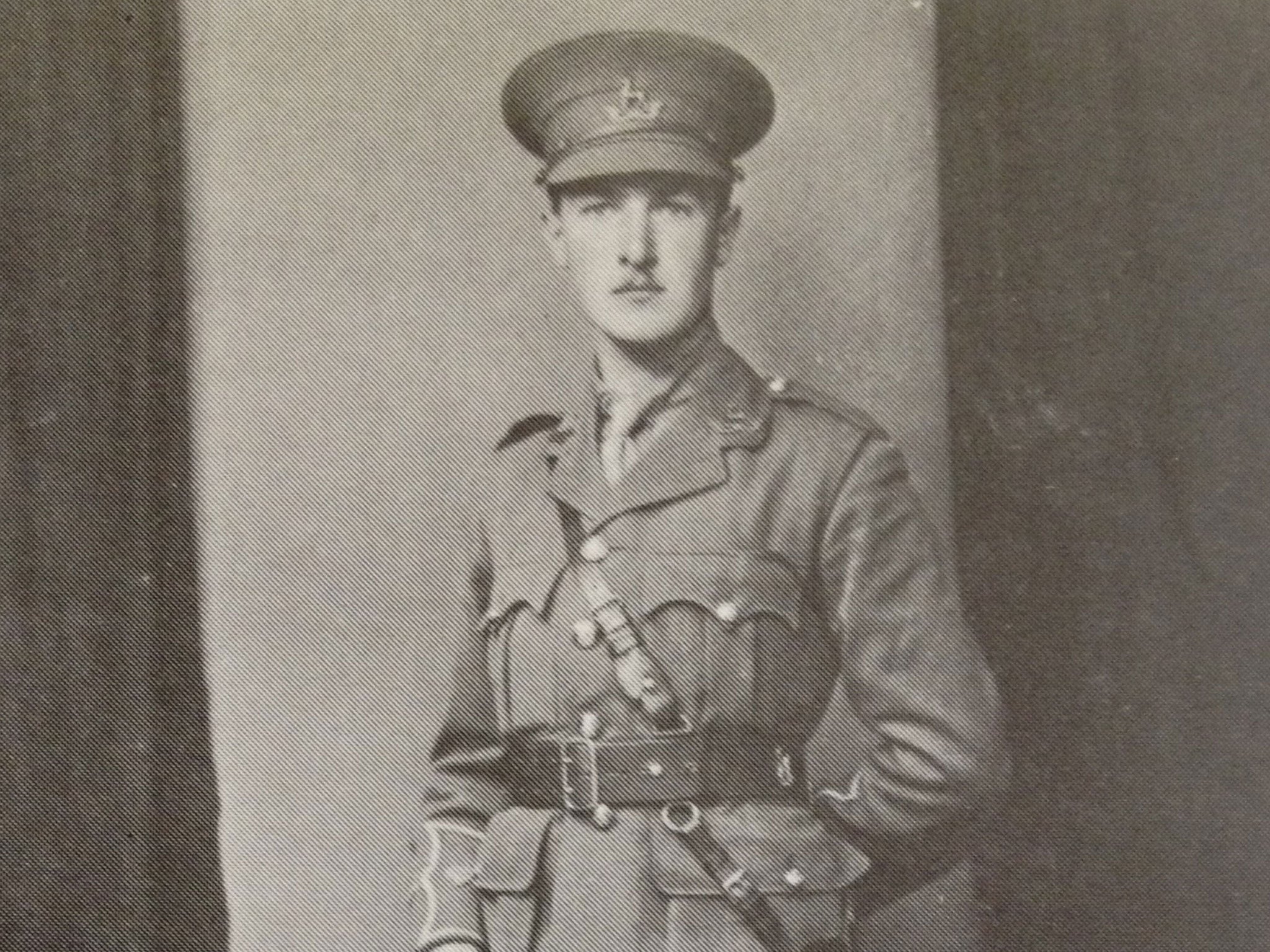

The diary is a large hardback army ledger, with GR for George V stamped on the front. In its pages, Edwin Vaughan wrote up the notes that he kept during eight months on the Western Front in 1917. Whether he thought he might be able to publish it, or whether he found the process in some way soothing, we will never know. His fluent longhand script, however, takes us from his time as the greenest of new officers through to the cataclysmic events of the battle of Passchendaele; all before he turned 20. In one of the photographs that we have, dated 1916, he has clearly just been commissioned. He stands with an officer's walking stick, his back ramrod straight, not a thread on his uniform out of place. He stares straight at the camera with the self-confidence of a man who has not yet heard a shot fired in anger. In another, taken in 1918, he appears somehow distracted. Perhaps it is my imagination, but he seems more like a man who has seen too much and cannot get it out of his mind.

Edwin Campion Vaughan was the son of an Irishman from County Offaly. His father had joined the Customs Service in England and married a Yorkshirewoman.

He was the youngest of five brothers and he had seen them all head off to war before his diary begins in January 1917. Commissioned into the Royal Warwickshires, he describes how he is "wrapped in the sense of adventure to come" as his train steams out of Waterloo station. This devout Catholic boy has enough self-awareness to know that he is heading into danger; he simply doesn't know how much. The early stages of the diary reveal a young man who comes over as bumptious, and that's clearly how he seemed to some of his colleagues. One tears him off a strip for being arrogant and inefficient and another encourages a commanding officer to send him out into no man's land to take him down a peg or two. Edwin is disarmingly honest about his own shortcomings after a few weeks in France, realising that he is "the most useless object". He solemnly relates how he nervously threatens a German in his dugout, only to discover it is a greatcoat hanging from a hook.

The early months of the diary describe a mix of genuine danger and high jinks that would not be out of place at an English public school. Disarmed grenades are dropped into bunkers to spook his fellow officers. Hours later, a shell falls in their trench and they are pulling out bodies.

Given the chance, Edwin, like most 19-year-old boys, would take the opportunity to get a drink and chat to girls. The best place for him to do this was the café called La Poupée in Poperinghe, always known as Pop, a few miles behind the line near Ypres. There, he and his fellow officers would drink plenty of "bubbly" and flirt with "Ginger". The teenage Eliane Cossey with her flaming red hair and charming smile clearly made a big impression on our young subaltern. "Over our cigars and liqueurs I offered her my heart," Edwin says, "which she gravely accepted." I imagine Ginger had to put up with a lot of that.

La Poupée is still there, in the main square of Poperinghe. Its façade is largely unchanged from the way it would have appeared in 1917. There is a small framed photo of Ginger, a local celebrity thanks to her appearance in several war diaries.

Steve Herat, the current owner, says that visitors still come by and ask about her and the role the café played in those awful years. Edwin recounts how Pop was regularly shelled by the Germans, and he and his friends praise the "pluck" of the young girls working there. Ginger survived the war and is buried in the local cemetery.

The diary really intensifies in July 1917. Edwin knows that something big is brewing. He even has it tacitly confirmed by Ginger, who picks up all the gossip from the officers at her tables. What he doesn't know is that he is about to be sent into a massive offensive that will be officially known as the Third Battle of Ypres and unofficially will be dubbed Passchendaele.

Edwin records how he is told that the German line consists of massive blockhouses which enfilade each other so that there is no shelter from their murderous fire. "I felt a terrible sinking inside when I heard this," he confides to the diary, "for it appeared that any attack must be unsuccessful." He did not know how right he was to be so worried.

The country north-east of Ypres today is quiet and in many ways unremarkable. There are fields of maize, small ponds, low-rise farm and industrial units. In the summer of 1917, though, it was a killing ground of mud and blood leading up to what was called Langemarck ridge, in reality a barely discernible lip of land. In the most intense and ghastly section of the diary, Edwin describes days of assault over this moonscape of mud. His friends are cut down one by one. The climax of the diary is the capture of one of those reinforced pillboxes he had so feared, which the British had named Springfield. Afterwards, in a lull in what has been days of fighting, Edwin becomes aware of a sound in the darkness:

"…faint long sobbing moans of agony and despairing shrieks. It was too horribly obvious that dozens of men with serious wounds must have crawled for safety into new shell holes, and now the water was rising about them and, powerless to move, they were slowly drowning… Dunham [his batman] was crying quietly beside me, and all the men were affected by the piteous cries."

Springfield no longer exists, but with the help of maps and locals I got a fairly good idea of its position, north of St Julian just before the Canadian war memorial. It is haunting to stand on the edge of the fields and look down on where so many died, imagining again the despair in the darkness.

Edwin seems to have been profoundly affected by the attack on Springfield. He is ordered to report to Brigade HQ and he sets off back towards St Julian. Today, the tree-lined road is surprisingly busy, but on that day it was under constant bombardment and appallingly dangerous. Edwin, however, records that he is "past caring". When the runner he has taken with him is killed, he states baldly that "we dragged him into a hole" and carried on. If this is not post-traumatic stress, it is something very like it.

Cheddar Villa is the name the British gave to a captured German blockhouse, which still stands beside that road. It is massive, made of reinforced concrete and was clearly too solid to be demolished as others were after the war. Today, it has been incorporated into farm buildings. The young, red-cheeked farmer spoke no English or French, and I no Flemish, but with a wave of the hand he motioned that it was fine for me to go through to the bunker. I wondered what he made of the visitors who came to look at what for him must be just a great concrete eyesore from another age.

Cheddar Villa was where Brigade HQ had been established in August 1917 and it was there that Edwin reported. It was incredibly moving to stand at the entrance to the blockhouse, knowing for certain that my grandfather had passed through it a century before. I may never have known him, but I could still picture this man, so desperately young, dazed and shocked. Strangely, I also knew more about him than he did back on that August day; that he would survive, meet a girl, marry and have children. His life, so fragile at that point, would be essential for my existence and that fact hit me hard inside the concrete walls of the blockhouse.

Edwin describes pushing aside curtains screening off rooms within and being sat down and offered whiskey. He says his superiors were "bucked" by the news that Springfield had been taken; it would be lost again within days. My grandfather, though, seems broken. Of his "happy little band" of 90 men, only 15 have survived. He goes back to his quarters to write his report, but instead he sits on the floor drinking whiskey after whiskey and "gazed into a black and empty future". It is less than eight months since he arrived in France.

The diary ends abruptly there. We know that later he was transferred to Italy to fight the Austrians. He was back on the Western Front by the end of the war, and he won the MC on 4 November 1918, a week before the armistice. He won it for capturing a bridge over the Sambre canal. On the same day, in the same place, Wilfred Owen was killed trying to get his men across the canal in boats. Perhaps, if the great poet had waited for my grandfather to capture the bridge, he might have survived.

Edwin did survive, as, remarkably, did his four brothers. He had trouble settling into civilian life, though, and it was during one of his periods of unemployment that he wrote up the diary. Eventually, he went back to the military, joining the RAF. At the age of 33, he went in for a relatively minor operation and was killed when wrongly injected with a form of cocaine instead of the anaesthetic novocaine. He left a widow and four children under the age of six.

So we have no memories of Edwin Vaughan. He lives in the pages of his diary, however, growing from the slightly priggish new boy to the old hand who has seen far too much; and he haunts some of the places around Ypres where he joked, drank, dreamed and suffered.

Andy Bell is the political editor of 5 News. His report about tracing his grandfather's story will appear on 5 News (on Channel 5) tonight at 5pm and 6.30pm.

An extract from Edwin Campion Vaughan's diaries (published as "Some Desperate Glory" in 1981 by Frederick Warne and republished by Pen & Sword in 2011) was featured in The Independent's recent series, "A History of the Great War in 100 Moments". The complete series will be available in ebook form from tomorrow, Saturday 2 August. For details go to independent.co.uk/ebooks

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments