Why is there a storm brewing over the right to plunder shipwrecks?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Magistrate Mark A Pizzo, sitting in the US Federal Court at Tampa, Florida, might not be a major figure in international law but he has just made a potentially vital decision on the future of 3,000 treasure-laden shipwrecks that lie in the world's oceans. Mr Pizzo ruled that an American marine archaeology company should return gold and silver coins worth £300m to the Spanish government after the bullion was removed from a sunken vessel in the Atlantic. Odyssey Marine Exploration removed the 500,000 coins, weighing 17 tonnes, in 2007 and flew them back to its Florida base from Gibraltar.

The move was greeted with fury by the Spanish government, which insisted the wreck was the Nuestra Senora de las Mercedes, a frigate which was sunk by the Royal Navy in 1804. Odyssey insisted there was not enough evidence to prove the site, which it called Black Swan, was the Nuestra Senora and, even if that were the case, the ship was on a commercial mission and its cargo could be legitimately recovered under salvage law and shared among salvors and claimants. Mr Pizzo dealt a serious blow to these plans when he issued a ruling that the sunken vessel was probably the Nuestra Senora and its glittering bullion should be returned in its entirety to Madrid. Odyssey has said it will appeal.

Why is a 205-year-old Spanish wreck so important?

The Nuestra Senora, whose sinking provoked war between Britain and Spain, goes to the heart of a debate about which shipwrecks can be explored and their cargoes retrieved. The 1989 International Convention on Salvage ruled that wrecks found in international waters were effectively there for the taking, requiring salvors to obtain "title" to the site which in most cases gives them ownership of whatever they can recover. But a key exception are the estimated 3,000 sovereign immune vessels which litter the world's seabeds.

These state-owned ships, including all naval vessels, remain the inalienable property of their originating nation. The US judge decided that the Nuestra Senora was a sovereign vessel despite evidence that it was on a commercial voyage taking privately owned gold from Peru. Odyssey's share value plunged on news of the ruling. If the recommendation is upheld on appeal, it could have major implications for the dozen or so underwater treasure hunting companies that have sprung up by obliging them to return their finds to government coffers.

Where have all these treasure hunters come from?

The marine archaeology business has been transformed in the past decade by the arrival of remote-controlled submersible robots which have allowed explorers to reach deep-water wrecks for the first time. Such exploration does not come cheap. The smallest remote operating vehicle (ROV), necessary for probing, photographing and retrieving artefacts from the sea bed, costs about £35,000. Odyssey operates a Land Rover-sized ROV called Zeus which cost up to £2.5m and is capable of picking up anything from a two-tonne cannon to a single coin as well as taking high-resolution photographs of a wreck site. Operating costs are vast – about £600,000 a month to run a fully-equipped survey ship.

Why aren't these wrecks protected sites?

In theory, they are. The 2001 Unesco Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, which Britain has agreed to observe, bans the commercial exploitation of all underwater historical material and states that the preferred action is for all material on the seabed to be left in situ. But to date only 15 countries have formally signed the convention and 20 signatories are required before it can be enforced. Crucially, the convention also contains a clause which allows artefacts to be brought to the surface if they are likely to be disturbed or destroyed on the seabed.

So is this archaeology or piracy?

Shortly after Odyssey announced in 2007 that it had discovered (and relocated to Florida) the Black Swan treasure, its vessels were confronted by the Spanish navy and the country's culture minister talked darkly of the need to "combat pirates". Ever since debate has raged about whether the exploration of wrecks is serious archaeology or naked profiteering behind a veneer of hi-tech science. Koichiro Matsuura, director general of Unesco, said: "Technical progress in detection and diving and escalating prices on the international market for objects snatched from the deep have led to the loss of many particularly valuable archaeological sites. The problem is further aggravated by the overly prevalent view of such archaeological sites as "treasures" that can be discovered or appropriated." Companies such as Odyssey insist there is a valid – and necessary – alternative. They insist that a rigorous archaeological examination of each wreck can be legitimately combined with a sale of surplus recovered artefacts such as coins or cannon to meet their running costs and turn a modest profit. Greg Stemm, the advertising executive turned founder of Odyssey, calls this "marrying archaeology with a business model".

How much treasure is out there?

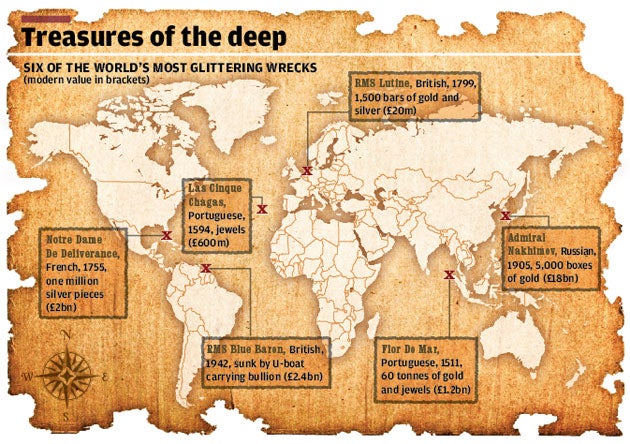

Nobody knows for sure but the figures are dizzying. To date, Odyssey alone has found four colonial and early 20th-century wrecks with bullion worth an estimated total of £1.8bn. The SS Republic, an American Civil War-era steamer discovered by Odyssey in 2003, has so far netted the company £29m in salvage fees and sales of artefacts including 51,000 gold and silver coins. The United Nations estimates there are anything up to three million shipwrecks around the world. Only a small proportion will hold valuable artefacts but Britain's territorial waters alone hold cargoes worth an estimated £15bn.

Has any of this British booty been found?

Yes. Odyssey has located the wrecks of at least three British vessels – HMS Sussex, HMS Victory and the RMS Laconia, a steam liner sunk in the First World War. The Victory, the predecessor to Nelson's flagship, was discovered last year with bullion estimated to be worth £700m on board. The Sussex, a 17th-century gunship, was sunk off Gibraltar with an estimated £300m of gold on board. The British government has struck a deal with Odyssey to share the proceeds of any gold found from the Sussex on a sliding scale designed to cover the salvors' costs and then give most of the profit to the taxpayer. Odyssey is seeking similar deals with the Victory and the Laconia, raising questions about British government involvement in "treasure hunting".

Why can't these wrecks be left as they are?

Commercial archaeology companies say the image of the seabed as an undisturbed oasis of colonial galleons and corroding steamers is entirely wrong with fishing trawlers and plastic waste ruining countless archaeological sites. Mr Stemm, of Odyssey, said last month: "The English Channel is like a giant industrial wasteland. The devastation we have found flies in the face of policy which is to preserve wrecks in situ. We are saying that this cannot be done and the most important artefacts must be raised."

Should deep-sea treasure-hunting be banned?

Yes

*Priceless archaeological sites are being plundered for profit rather than scientific study

*Sediment and the lack of oxygen under the sea preserves artefacts better than on land

*Shipwrecks are often submerged cemeteries, in many cases the last resting places of war dead

No

*If digging is permitted on land, then searching the seabed is equally valid to boost knowledge

*Wreck sites are being rapidly degraded by commercial fishing and discarded waste

*Multiple identical artefacts are of little archaeological value and should be sold to fund exploration

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments