Time running out for settlement to disarm Iran's nuclear programme

Deadline looms for talks in Vienna but few details appear settled

The good news is that after a decade-long face-off between the international community and Iran over its nuclear programme, negotiators are the closest they have ever been to resolving it.

The less good: the last few feet of this very arduous climb will be the toughest and time is running out.

The stakes are daunting, not least because of the tantalising promise of detente between Tehran and Washington. Yet last night US officials were lowering expectations, warning that as negotiators from all sides headed to Vienna for the start this morning of what is meant to be one last heave to the top, the chances of getting there before a pre-agreed deadline of 24 November were looking slender.

The goals of each side are ostensibly straightforward. Facing Iran are the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany, which can be translated to mean the United States, the European Union and Russia. They want Iran to degrade its programme to the point where it would take minimum one year for it to build an atomic bomb. Iran, thus, could pull no sudden nuclear surprise.

Iran meanwhile wants everyone – the EU, the UN and the US – to lift the very heavy web of economic sanctions imposed on it that has dragged its economy close to the plughole, causing deepening domestic discontent, notably by cutting off exports of its oil as well as imports of technology and arms.

So far so good, but nothing is simple here. How will these steps be achieved and in what order? Iran is being asked concurrently to surrender most of its roughly 20,000 centrifuges that are vital to enriching uranium needed for a warhead, to ship much of its stockpile of existing enriched uranium to Russia and to submit to intrusive inspections. It, in the meantime, is demanding that the UN sanctions in particular be lifted at once. Few, if any, of these details appear to have been settled.

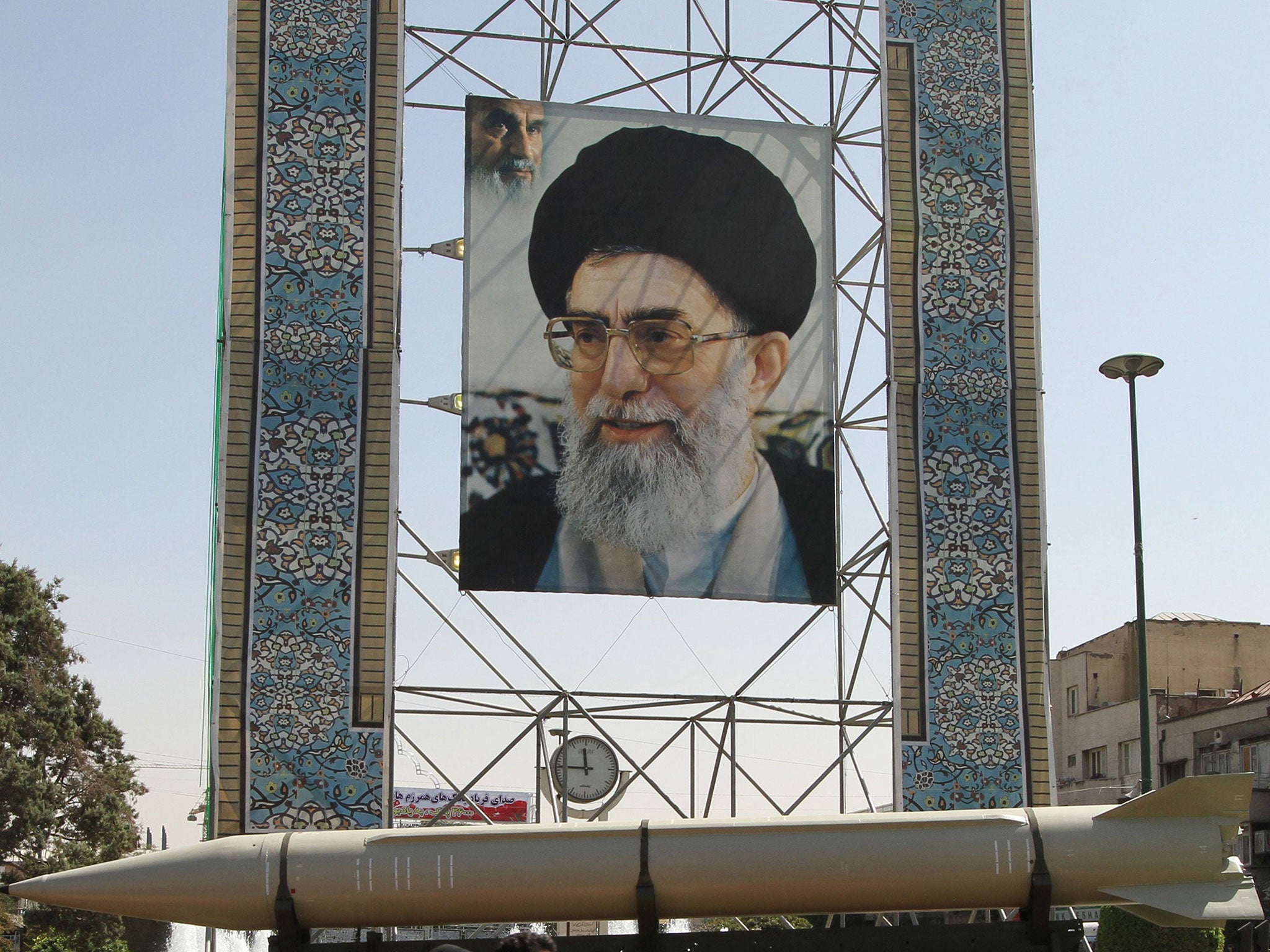

Then there are all the other forces beyond the negotiating room, among them Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. It was with good reason that President Barack Obama, for whom achieving this deal is especially important, wrote to Iran’s Supreme Leader last month urging him to embrace a final deal (and help confront the forces of Isis). While it may be that President Hassan Rouhani, elected last year, might be ready to accept a final agreement, he can only do so if Khamenei says yes.

But if everything comes down eventually to one man in Iran, that is not the case for the United States. Iranian negotiators may go into the talks this week expecting to have greater leverage because of the beating Mr Obama took in this month’s US midterm elections. But they should also know that newly emboldened Republicans are deeply sceptical of what is being negotiated and are likely to resist any fast easing of US sanctions. In fact they want more and the clamour will increase if a deal isn’t done now.

This is shared even by some in Mr Obama’s own party. “We believe that a good deal will dismantle, not just stall, Iran’s illicit nuclear programme and prevent Iran from ever becoming a threshold nuclear state,” Senator Robert Menendez, the Democratic chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and Senator Mark Kirk of Illinois, a Republican, said in a joint statement, adding they would seek new sanctions if “a potential deal does not achieve these goals”.

Breathing heavily into the ears of Mr Obama and Congress meanwhile are the other big players in the region. Israel is apoplectic at a deal they think would essentially leave Iran as a threshold nuclear power. Saudi Arabia has equally voiced alarm. The Sunni-led kingdom sees mortal danger in Shia Iran being unfettered. Everyone at the table in Vienna – especially US Secretary of State John Kerry and his Iranian counterpart Javad Zarif – will know that for a deal to stick it will have to be crafted in such a way that both sides can claim the other caved. Otherwise it will be killed off the minute it leaves the room.

If they can’t? The best scenario would be a deadline extension to keep the effort going. The worst would be final breakdown and a defiant push by Iran to resume its programme. That in turn could trigger one more disastrous military confrontation in a region that desperately doesn’t need one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments