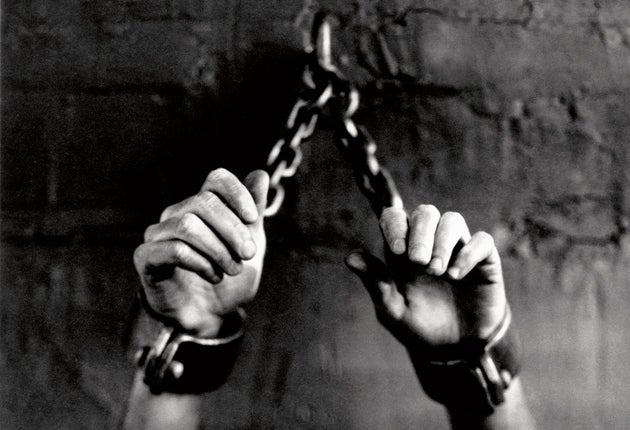

The £1 billion hostage trade

How kidnapping became a global industry. Esme McAvoy and David Randall investigate.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week, the British aid worker Linda Norgrove was killed when US forces stormed the camp of the group holding her to ransom. In September, eight tourists died during a botched hostage rescue in Manila.

In August, three Russian airmen were kidnapped in Darfur. In July, four journalists were seized in Mexico. In June, a Russian businessman's grand-daughter was taken hostage. In May, it was Chinese technicians in Nigeria; in April, eight Red Cross workers in the Democratic Republic of Congo; in March, a British film-maker in Pakistan; in February, four Pakistani employees of a US aid agency; and in January, a US contractor in Iraq.

A ship seized off Somalia was redeemed for $7m, (£4.4m) a ransom of $550,000 was paid for a German banker's wife, and, with $300,000 for an oil worker here and $10,000 for a shopkeeper's son there, and with governments and insurers making their secret cash drops, it all adds up. If you are a hostage-taker, 2010 is turning out to be a very profitable year.

From Mexico City to Mogadishu, from Mosul to Manila, the numbers of aid workers, Western staff, tourists and locals taken hostage is rising. In Mexico, more than 7,000 were held in 2008 alone, in Nigeria at least 1,000 were taken last year, and in Somalia, foreigners are being kidnapped at a rate of 106 a month. All told, at least 12,000 people are now taken hostage each year, and this weekend more than 2,000 – at least 400 of whom are foreigners – are enduring yet another day in a makeshift "prison", not knowing, from hour to hour, if they will be freed or whether, once their trade-in value is no longer worth the trouble of their keep, they will be dispensed with. And these numbers do not include the many thousands of children who are abducted as part of marital disputes, or the thousands of women victims of bride kidnapping.

The ransom profits are enormous – and growing. Police in Nigeria estimate that ransoms paid there between 2006 and 2008 exceeded $100m. Al-Qa'ida in West Africa alone makes millions taking hostages. What was once an activity undertaken mainly by insurgents and guerrillas keen to make a political point, or acquire a human bargaining chip, is becoming increasingly commercialised. These days, most hostages are taken for ransom, with sums as high as $1.6m paid for their safe return.

And so has grown up a whole industry to counteract the criminals: firms offering kidnap and ransom insurance, highly paid negotiators, lawyers, and security personnel. Today, after an investigation prompted by Anthony Grey, the Reuters journalist who was held hostage in China for 27 months in the 1960s, we reveal the extraordinary extent of one of the 21st century's least welcome success stories – the hostage industry, worth at least £1bn a year.

Its "employees" range from the teenage hoodlums who roam Sudan or West Africa ready to kidnap the child of a businessman or an American oil worker and sell them to more experienced hostage gangs, to statisticians in London offices keeping check on the going rate for the safe return of, say, a Western oil worker (about $350,000), so the actuarial calculations can maintain a healthy bottom line. The business's raw material is unprotected people, what has been called "walking gold" – someone in the wrong place at the wrong time who can be taken and converted into serious money.

The public perception is that hostages are mainly people like Terry Waite (the Archbishop of Canterbury's special envoy, who was held by an Islamic group in Beirut for nearly five years), or John McCarthy (held in Beirut for five years by Islamic Jihad), and Brian Keenan (four years as an Islamic Jihad hostage in Beirut). All were taken to try to force the hand of their governments as part of some wider dispute, or to publicise the cause of an insurgency. But although states still sometimes detain people to make political capital, the average hostage is more likely to be a Mexican seized by a drug cartel, a Nigerian oil man, or people like Paul and Rachel Chandler, the British couple from Tunbridge Wells whose yacht was scooped up by Somalian pirates.

Hostage-taking used to be considered a South American problem – until 2004, the region accounted for 65 per cent of all kidnap cases worldwide. Last year, the figure fell to 37 per cent as hostage-taking boomed elsewhere: the Philippines, Afghanistan, Nigeria, the Gulf of Guinea, Mexico, Sudan (markedly increased since 13 aid agencies were expelled in March 2009), the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan (five cases a week), north-west Africa, Iraq, Nepal, Haiti (foreign business people, construction workers and aid agency staff have been taken recently) and Yemen (a hot-spot where at least 220 foreigners have been seized since 2004).

The treatment of hostages varies enormously. Mexican hostages are not treated well, and are liable to lose a hand if the kidnappers think the ransom payers need geeing up. If that doesn't work, the hostage is likely to die. In Nigeria, by contrast, hostages are rarely harmed, and kidnappers have been known to drive into Port Harcourt to collect their hostages take-away hamburgers.

The Taliban in Afghanistan and insurgents in Iraq, as well as criminals, now use hostage-taking to raise funds. Since 2004, an estimated 200 foreigners and thousands of nationals have been taken hostage in Iraq. The business has now largely turned to abducting locals, but at least 15 foreign hostages are still being held there or remain unaccounted for.

Nigeria is third on the security company AKE's "top 10" hostage hot-spots. Since 2006, militant groups in the Niger Delta have kidnapped more than 200 foreign oil workers, with 21 foreigners taken this year. As oil companies respond to the threat by withdrawing foreign staff or hiring hi-tech private security, militants have switched to kidnapping middle-class Nigerians and their children. Despite the "going rate" for these ransoms being a fraction of that extorted for foreigners (under $30,000 compared to an average of $200,000 for foreigners), more than 500 Nigerian hostage cases have been reported this year.

The victims are known to us by name occasionally – people such as Johannes and Sabine Hentschel, Stephane Taponier, and Herve Ghesquiere. But tens of thousands of them are listed merely as "aid worker", "engineer" or "son of a local businessman", if they are identified at all. The secrecy of the industry, and the scale of hostage-taking, means media coverage soon peters out. This renders these victims, in the warped accountancy of this trade, people of little importance to any but their family and friends. Even these, invariably local nationals, are redeemable for surprising amounts. The abducted son of a Baghdad sweetshop owner was released after his father cleaned out his life savings to pay $10,000. Western workers, or ships, are worth far more. Two Germans seized in Nigeria netted their kidnappers $430,000; and $7m and $3m have been paid for the return of ships in the past year or so.

Even worse are the cases where nervy or impatient hostage-takers don't get what they want immediately. Last year, a Baghdad boy was killed because his mechanic father could not raise $100,000 in 48 hours. And then there was Maria Boegerl, the wife of a German banker. Her husband left $550,000 in a bin bag at a precise spot beside the A7 autobahn as specified by the kidnappers. They did not collect, silence ensued and her body was found several weeks afterwards. It later emerged that the bag may well have been cleared away by efficient German rubbish collectors.

Governments, for all their denials, are not averse to paying. In August, the Spanish government was criticised for allegedly paying out a hefty ransom to al-Qa'ida to secure the release of two Spanish aid workers who were taken hostage in Mauritania in November last year. The Spanish daily newspaper El Mundo reported that their release was the result of a payment of more than £5m. In 2006 it was revealed that France, Italy and Germany had paid out ransoms ranging from $2.5m to $10m per person to free nine hostages held in Iraq. In less than two years, the deals totalled $45m. The British government insists it never pays, but it does have an instinctive taste for secrecy. When this newspaper first asked the Foreign Office how many Britons are held hostage, we were told to make a Freedom of Information request.

Getting back a hostage is now far more likely to be a matter for private enterprise. Enough of the hostages work for Western companies – firms such as Chevron, Adobe, Halliburton and Royal Dutch Shell have all had staff kidnapped – for hostage insurance and its associated trades to have become big business. Three-quarters of Fortune 500 companies, the top companies in the US, have kidnap and ransom insurance, and this means that they will have to engage hostage consultants to assess the risk, advise on security, and, if it goes wrong, negotiate with kidnappers, and babysit the family. The premiums paid worldwide for such insurance are now close to $400m.

John Chase, an experienced hostage negotiator and director of crisis response for AKE, said: "The insurance industry in London was the first to underwrite K&R [kidnap and ransom] risk in the late Seventies, and that started the commercial industry as we know it today. There were two main underwriters then. Now there are four who, between them, cover about 98 per cent of all insured hostage cases. Each is tied to a crisis response team who negotiate for the hostage's release."

For people like Mr Chase, there's no hostage situation money can't resolve. "Every single case can have a financial conclusion to it, even those that start with political demands," he says. "In each country there's a 'going time' [how long hostages are held] and a 'going rate' [for ransoms]. It's strictly a business, and every hostage-taker has their price." Ransoms demanded by pirates operating off the coast of Somalia are extortionate, and increasing. According to Mr Chase, the "going rate" used to be $1.5m but now it's doubled to $3m. It doesn't stop there. As well as insurance, negotiators, minders and the ransom, air freight companies are being paid to drop the cash to the kidnappers. Charter firms, operating out of states such as Kenya, which normally fly tourists to safari parks, have diversified, offering ransom delivery services to vessels in the Gulf of Aden for around $250,000 per drop.

The hostage business is getting increasingly sophisticated for the pirates, too. Ransom payments suddenly flood an impoverished coastal town with unimaginable millions, causing prices of staple foods in the market to double or triple. The inflation leaves ordinary people unable to buy the basics. A recent BBC documentary revealed how ingenious pirates have set up a pirate "stock exchange" to encourage investors and build an economy, albeit a black one. Pirate groups of a certain size register themselves in the same way that established companies can on a regular stock exchange. Individuals can then choose to invest in one or more groups, by donating weapons or buying shares. They then get a cut of the earnings when their pirate group strikes lucky.

The huge sums involved in the hostage business, the vesting of so many interests and the instincts for secrecy of the individuals, companies and governments involved make many with a legitimate expertise uneasy. Although there are worldwide bodies for everything from minor medical conditions to arcane sports, not one exists to monitor, study, care for or attempt to release people taken hostage. Anthony Grey asks: "Why is there no international body for handling hostage cases around the world and taking action?" Another former British hostage, Terry Waite, said: "Hostage cases are often mired in political controversies. Perhaps hostage negotiation should be put into the hands of an independent, not-for-profit organisation, under the auspices of the UN or Red Cross, rather than left to private firms or national governments."

Alan McMenemy: Scottish security guard Alan McMenemy, 34, was abducted in Iraq by a Shia militant group along with three other British security guards and a computer programmer, Peter Moore, more than two and a half years ago. Investigations suggest that the five were taken over the border into Iran and held there. Mr McMenemy’s fellow security guards – Alec MacLachlan, Jason Swindlehurst and Jason Creswell – were executed and their bodies passed to UK authorities last year. Mr Moore survived and was freed on 30 December last year. Alan McMenemy is the only hostage who remains unaccounted for. British officials believe he is dead but there has been no confirmation from militants.

Johannes And Sabine Hentschel: Johannes Hentschel, a German engineer, and his wife, Sabine, a nurse, were taken hostage in Yemen in June 2009 by suspected Shia rebels with their three young children, Lydia, Anna and Simon, and four others. The nine-strong group included a British engineer, Anthony Saunders, two German care workers and a South Korean teacher. They were seized while having a picnic in the north of Yemen. Mr Saunders had been working in a hospital as part of a Christian Aid project. Both care workers and the teacher were found dead a few days later. In May this year, Lydia, five, and her sister Anna, four, were freed by Saudi Arabian special forces. There was no sign of their parents, younger brother or Mr Saunders.

Stephane Taponier and Herve Ghesquiere: French reporter Hervé Ghesquière and cameraman Stéphane Taponier were working in Afghanistan for French state TV channel France 3 when they were seized in December last year along with three Afghan colleagues. They were drivingunescorted in Kapisa province, north-east of Kabul, when their car was ambushed by Taliban militants. An adviser for French President Nicolas Sarkozy announced this week that a recent proof-of-life video shows that the French pair are alive and well. There is no word on their Afghan co-workers. The Taliban group is holding the hostages in the hope of negotiating a release of prisoners detained in Afghan or US prisons.

Additional research by James Burton

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments