11 ways the world got better in 2015

After a year of bad news you'd be forgiven for thinking the world is going to hell in a handcart – here's why you'd be wrong

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As 2015 draws to a close, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who’d claim that it’s been a good year for the human race. The bad news has been relentless: war in Syria, a refugee crisis in Turkey and Europe, earthquakes in Nepal, terrorist attacks in Paris, mass shootings in the US, floods in India.

With the media screaming blue murder and social media feeds filled with complaints about how selfish/materialistic/short-sighted our fellow human beings are, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the world is going to hell in a handcart.

You’d be wrong, though.

Franklin Roosevelt once said: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.” And if we apply that criterion to the world as a whole then 2015 was a very good year indeed. Here’s why:

1. We got a lot closer to global, universal education

In April this year, Unesco released a report on the status of global education, showing that in the last 15 years the number of children around the world without access to education has nearly halved, from 100 million to 57 million. This is thanks to an increased appreciation of the benefits of education to the individual and society, increased government provision, and increases to mandatory minimum years of schooling. It’s an incredible achievemen: it means that we are in a world where nine out of 10 children are learning to read and write. The World Bank now says we’re only one generation away from a world where every single person is literate.

2. Extreme poverty dropped below 10 per cent – the lowest rate on record

The number of people in extreme poverty (defined as living on less than $1.90 a day) fell to 702 million in 2015, or 9.6 per cent of the global population – down from 902 million people, or 12.8 per cent, in 2012. It’s the lowest number of people living in extreme poverty in the last 200 years. It gives us fresh evidence that a quarter-century-long effort is moving the world closer to ending poverty by 2030. As Jim Yong Kim, the president of the World Bank, says: “This is the best story in the world today – these projections show us that we are the first generation in human history that can end extreme poverty.”

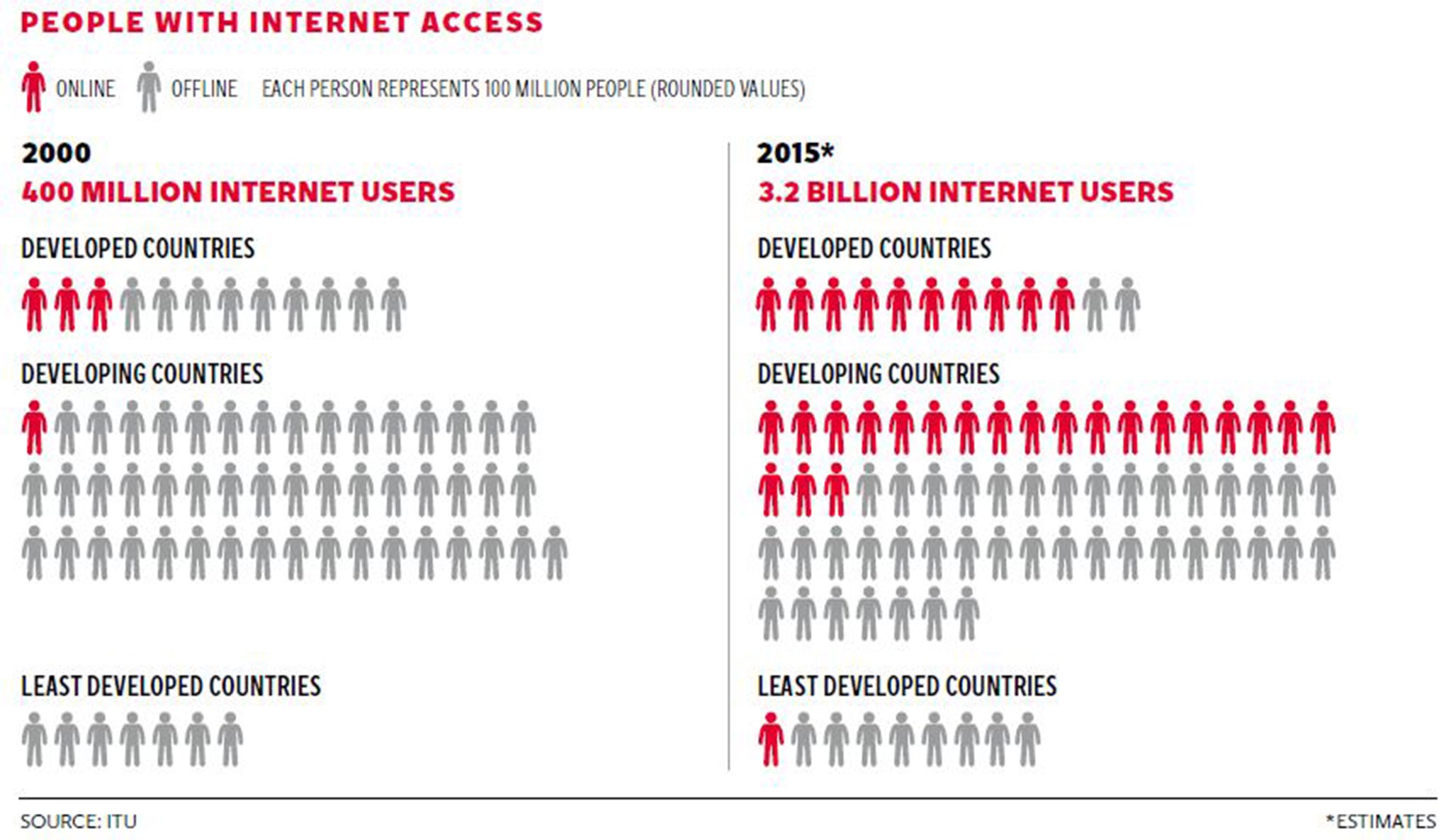

3. More people got connected to the internet than ever before

Globally, there are now 3.2 billion people online, two billion of whom are from developing countries. In 2000, those numbers were 300 million and 100 million respectively. It means the number of people with internet access has seen an eightfold increase in just 15 years. Of course, there’s still a long way to go. In the least developed countries, only 9.5 per cent of the population have internet access, compared with 35.3 per cent for developing countries and 82.2 per cent for developed countries. But those numbers are changing fast. Africa’s internet capacity, for example, has grown by 51 per cent over the past five years. And mobile phones are leading the charge. Globally, subscriptions number more than seven billion, and 95 per cent of the world’s population are now within reach of a mobile network signal.

This year showed us that the next billion people coming online will do so from cheap mobile phones. There have been no courses, no tutorials, no NGOs showing up to “deploy” phones or to train people. The mobile internet is so intuitive, and so obviously useful, that it’s become the quickest technology uptake in human history. For every 10 people who gain internet access, around one person is lifted out of poverty and around one new job is created. And remember: thanks to our successes in education, all of those new users can read and write. They represent tens of trillions of dollars of new economic buying power, and an extra billion people who’ll have the networking ability of the internet at their fingertips.

4. Millions of people gained access to finance for the first time

In April this year, a little-known organisation called Global Findex released the largest global research project on financial inclusion in history. Based on interviews with 150,000 adults in more than 140 countries, it showed that between 2011 and 2014 an additional 700 million people became account holders at banks, other financial institutions, or mobile money service providers, and the number of “unbanked” individuals dropped by 20 per cent. This trend was driven in particular by new mobile money accounts. Countries such as Ivory Coast, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe now have more adults using a mobile money account than an account at a financial institution.

This matters, because access to financial services is widely perceived to be a driver of development, especially in low-income countries, where 54 per cent of the population have no access to traditional banks. That’s why the mobile explosion has been so important. For the 700 million people who just gained access to finance, digital payments, through a mobile phone or a point-of-sales terminal, create opportunities to provide more convenient and affordable payment options. It means they’ll be able to start businesses, save and transfer money, invest in education, and deal better with financial shocks.

5. Aids deaths came down for the 15th year in a row

In the 1980s and 1990s, Aids was seldom out of the headlines. We got used to seeing daily reports of the devastation it caused, and many people expected the death tolls would continue to rise. For the 37 million people around the world living with Aids today, though, the disease is both treatable and preventable. Thanks to a concerted global effort to improve access to antiretroviral drugs we’ve turned the corner in our fight against this terrible disease.

UNAids says that 41 per cent of all people who are HIV-positive are now being treated, nearly double the percentage in 2010. There were two million new HIV infections around the world in 2014-15, the lowest since 2000. Deaths are also coming down, from a high of two million in the early 2000s to 1.2 million this year. As the graphic on the right shows, the goal of UNAids is to end the epidemic by 2030. It will take more money, more political support and more work. But what we saw this year was that the possibility of an HIV-free generation is now within sight.

6. Malaria death rates are at a record low

Malaria is one of the world’s biggest killers, responsible for more deaths than all car accidents around the world. In the past decade, though, we’ve finally got serious about tackling the disease. That’s thanks to the scale-up of three key malaria control interventions: insecticide-treated mosquito nets, indoor residual spraying, and artemisinin-based combination therapy. Since 2000, for example, nearly one billion insecticide-treated mosquito nets have been distributed in sub-Saharan Africa alone.

Mortality rates have declined by 85 per cent in South-east Asia, by 72 per cent in the Americas, by 65 per cent in the Pacific, and by 64 per cent in the Middle East. While Africa continues to carry the highest malaria burden, over the last 15 years mortality rates have fallen by 66 per cent among all age groups, and by 71 per cent among children under five, a population particularly susceptible to the disease. Globally, the number of malaria deaths fell from an estimated 839,000 in 2000 to 438,000 in 2015. That means we’ve saved an estimated 6.2 million people from malaria in the last 15 years – an amazing achievement no matter which way you look at it.

7. Polio is about to be eradicated for good

Twenty-five years ago, a number of international healthcare organisations set out on a quest to stamp out polio throughout the world. With 350,000 children affected and more than 1,000 paralysed daily, it seemed like an unlikely goal. Since then, more than $9bn has been invested, and more than 2.5 billion children across the world have received vaccinations. As a result, the number of polio cases has been reduced by 99 per cent, and this September the World Health Organisation announced that polio was no longer endemic in Nigeria, paving the way for it to become the final African nation to be declared officially polio-free in 2017. That leaves just two countries with wild polio cases: Pakistan and Afghanistan. If, as health professionals predict, the 334 cases found there are eradicated within the next few years, then a disease that once killed and maimed children in their tens of thousands will join smallpox and the guinea worm as plagues consigned to history.

8. Fewer people went hungry this year than ever before

Of the 7.3 billion people on the planet, an estimated 805 million – or one in nine – suffered from chronic hunger between 2012 and 2014. However, that number has dropped by around 200 million since a quarter of a century ago. That’s pretty impressive, especially when considering that the world’s population grew by 1.9 billion people during the same period. And the rate of hunger is also declining. In 1990, one of the goals we set ourselves as a species was to halve the hunger rate. Today, 72 of 129 developing countries have met that goal. That’s happened in countries with huge populations such as Nigeria and Ethiopia, and also in smaller countries such as Malawi, Ghana and Mali. Globally only 12.9 per cent of the population in developing regions are hungry today, compared with 23.3 per cent a quarter of a century ago.

9. More people have access to clean water

One of the least talked-about success stories of 2015 was one of the most important. This year, the number of people without access to improved drinking water fell below 700 million for the first time in history. It means that more than 6.6 billion people, or 91 per cent of the global population, now use an improved drinking-water source, up from 76 per cent in 1990. In 2015, only three countries – Angola, Equatorial Guinea and Papua New Guinea – have clean-water coverage of less than 50 per cent, compared with 23 countries in 1990. In sub-Saharan Africa 427 million people gained access to clean drinking water, an average of 47,000 people per day, every day, for the last 25 years.

10. Child mortality plunged for the 43rd year in a row

The mortality rate for children under five has dropped in virtually every country. This is thanks to progress in the fights against diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, vitamin A supplements, new HIV/Aids medication and better treatment of diarrhoea and pneumonia. It means that in 2015, for the first time on record, the global child mortality rate (defined as child deaths under the age of five) dropped below the six million mark. In the last 25 years, roughly one-third of the world’s countries – 62 in all – reduced under-five mortality by two-thirds, while another 74 reduced rates by at least half. And the progress has come from some of the worst-hit countries; 10 of the 12 low-income countries that reduced under-five mortality rates by at least two-thirds, for example, are in Africa.

This means that about 19,000 fewer children died per day in 2015 than in 1990, the baseline year for measuring progress. Since 2000 alone, we’ve saved the lives of 48 million children. Think about that for a second. That’s higher than the combined totals of all deaths from war and violence around the world during the same period. It means that fewer parents, as a proportion of the world’s population, had to bury their children this year than at any other time in human history. It’s one of the most astonishing news stories of our time, and yet it was outnumbered 100 to 1 by stories on terrorism.

11. We reached a tipping point in the fight against climate change

Three big things happened in climate change politics this year. The first is that 2015 looks set to be the hottest year on record. That means that temperatures have now risen by 1C since the Industrial Revolution. The five-year period between 2011 and 2015 is also the hottest on record; and as the records tumble, the claims of climate change deniers are becoming increasingly ridiculous. We’ve turned the corner; denial is no longer being taken seriously. The world has moved on, and contrarians have become irrelevant relics of the fossil fuel age.

The second thing is that thanks to sharp declines in Chinese coal-burning and a continued surge of renewable energy worldwide, 2015 looks set to be the first year in history that CO2 emissions declined during a year when the overall global economy grew. That follows from 2014, where emissions flatlined. The Chinese data is particularly important. Whether their energy transition is permanent is not clear yet, but the signs are encouraging. In wealthy, developed countries, on the other hand, the signs are obvious. They’ve hit a peak in overall fossil fuel consumption and are now making the transition to cleaner forms of energy.

The third, and most important, thing that happened for climate change this year was the signing of the Paris Agreement. At its core is a so-called “long-term goal” that commits almost 200 countries to hold the global average temperature to below 2C above pre-industrial levels and to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C”. The long-term goal also states that in the second half of this century, the world should get to a point where the net emissions of greenhouse gases should be zero.

Sure, it isn’t good enough. There’s a long way to go before the pledges match up to that target. But it’s still a lot better than expected, and a triumph for diplomacy: the largest gathering of world leaders in history, on the biggest issue humanity has faced, and it ended in a legally binding instrument that all countries agreed to. The commentator Jonathan Chait sums it up perfectly: “Those who have consigned the world to its doom should reconsider. The technological and political underpinnings are at last in place to actually consummate the first global pact to limit greenhouse gas emissions. The world is suddenly responding to the climate emergency with – by the standards of its previous behaviour – astonishing speed. The game is not over. And the good guys are starting to win.”

The world is not a perfect place. Many things went wrong for humanity this year. You’ve heard a lot about them. We still have major problems, in particular around environmental degradation, international migration, political extremism and economic inequality. These are the big challenges of our time. And it’s also true that the surge of progress has not reached everyone. Far too many people still live in extreme poverty, six million children still die every year of preventable diseases and hundreds of millions of people cannot exercise basic freedoms. But as one of my favourite statisticians, Hans Rosling, says: “You have to be able to hold two ideas in your head at once: the world is getting better, and it’s not good enough!”

It’s easy to be cynical and maintain that nothing is ever getting better. The empirical evidence flatly contradicts this view; looking at what we’ve already achieved as a species should give us confidence going forward into the future. We constantly underestimate humanity’s abilities to work co-operatively, meet new challenges and expand global prosperity and basic freedoms. We now have a window of opportunity to create the greatest era of sustainable progress in human history. Doing so will not be easy, just as it has not been in the past, and it will take courage, sacrifice and strong leadership. But the potential gains are staggering. And if we can pull it off, we might just be on the cusp of a golden age for the human race and for the earth we live on.

Dr Angus Hervey is a political economist, science communicator and co-founder of Future Crunch, a forum for critical debate on the transition from the industrial to the digital era. He is also the Australian manager of Random Hacks of Kindness, a global initiative connecting technologists with charities and community groups, to create open-source solutions to social challenges.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medium.com

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments