Paris terror attack: The booming black market for fake Syrian passports

Fraudulent Syrian passports are nothing new on the migratory route from Turkey through Europe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The terrorist who blew himself up outside the Stade de France had fingerprints matching that of a man who arrived on European shores Oct. 3 alongside desperate migrants who had crossed over from Turkey, according to French and Greek officials.

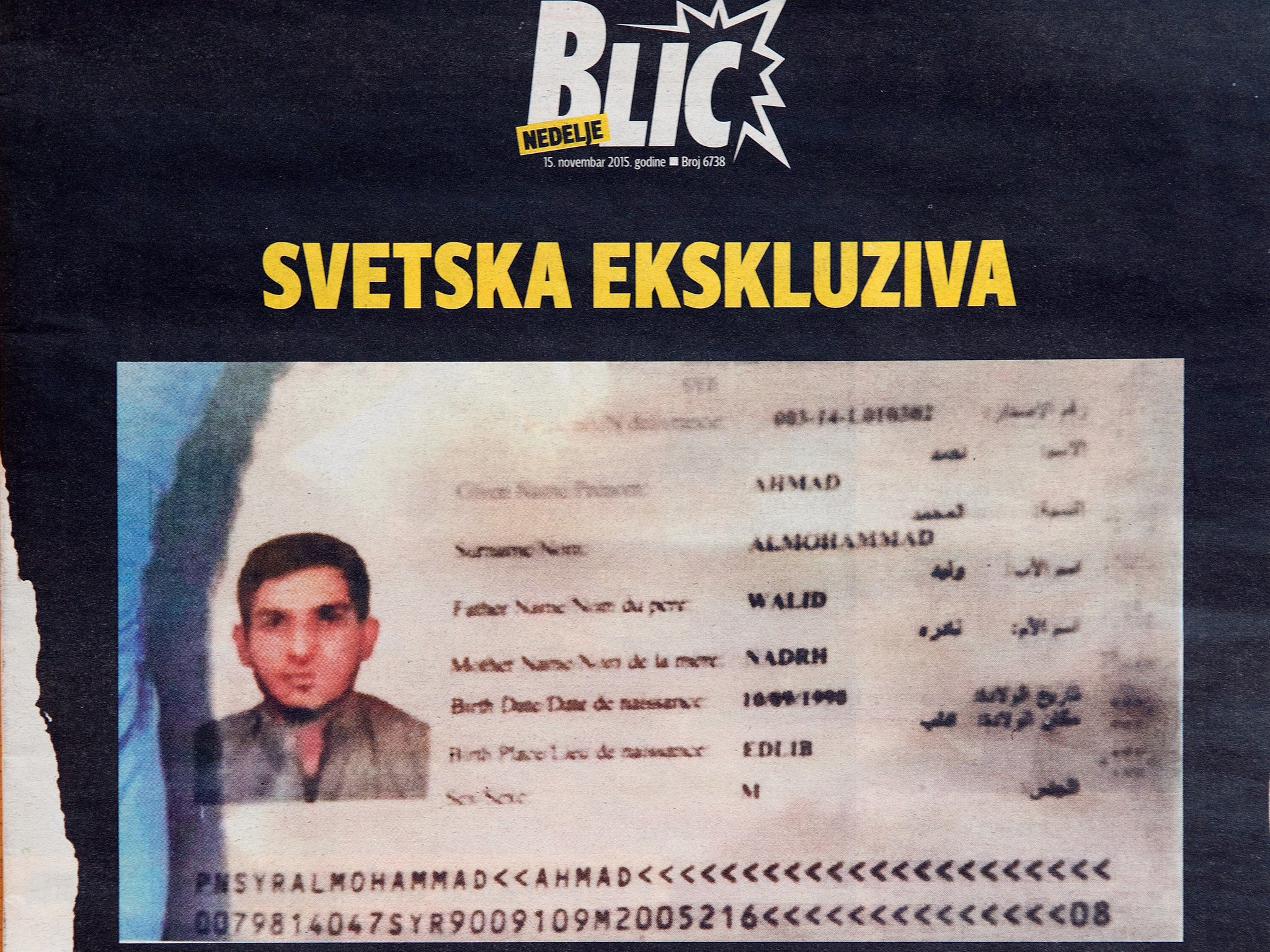

But the Syrian passport found near his body, which quickly sparked a political debate in Europe and the United States? It was a fake.

Fraudulent Syrian passports are nothing new on the migratory route from Turkey through Europe. Indeed, German officials this year estimated that nearly a third of asylum seekers falsely claimed they were Syrian.

That's because a Syrian passport has become a valuable item, as European nations have pledged to grant asylum to refugees from the Middle Eastern nation.

A range of individuals seek seek fraudulent Syrian documents. Many of them are so-called economic migrants who take life-threatening risks to get to Europe in search of a better life but aren't granted the same welcome as those fleeing conflict in Syria, Iraq and Eritrea. As The Post reported in September, among the flood of Syrian war refugees seeking asylum are other migrants — Iranians, Pakistanis, Egyptians, Somalis and Kosovars — some of whom pose as Syrians.

From that story:

Many of the asylum seekers tell journalists and aid workers that they are from Syria, even if they are not, under the assumption that a Syrian shoemaker fleeing bombed-out Aleppo will be welcome, while a computer programmer from Kosovo will not be.

It is common knowledge on the migratory route that some who are not from Syria shred their real passports in Turkey and simply fake it.

A couple of reporters, one a native Arabic speaker, who wandered through train stations in Vienna found plenty of newcomers whose accents did not match their stories and whose stories did not make sense.

The head of European border agency Frontex Fabrice Leggeri said such individuals have come to view Syrian passports as a ticket to the European Union.

"There are people who are in Turkey now who buy fake Syrian passports because they know Syrians get the right to asylum in all the member states of the European Union," Leggeri told French radio station Europe 1 in September, according to AFP. "People who use fake Syrian passports often speak Arabic. They may come from North Africa or the Middle East but they have the profile of economic migrants," he said.

Syrians themselves are also in the market for fake Syrian documents, or official passports belonging to other people. Frontex spokeswoman Ewa Moncure told NPR in September that "most fraudulent Syrian passports are used by Syrians" and that migrants who actually have legitimate documents "are an exception."

"They are coming from a war-torn country," Moncure said. "Probably many had to leave their homes rather quickly. Maybe some didn't have passports, and obtaining a Syrian passport right now — it's probably extremely difficult."

The passports are so valuable that Syrians with legitimate documents can be targeted by smugglers. The Guardian profiled a Syrian migrant named Mohamed who became a victim of passport theft:

When Mohamed paid an Afghan smuggler several hundred euros to drive him and his friends from Thessaloniki to the Greek-Macedonian border in July, he thought the money was all the smuggler would want. Instead, once on road the driver feigned a problem with the engine and persuaded the Syrians to leave the car on the pretext of avoiding detection by the police. “And then he stole our passports,” said Mohamed.

A reporter with the Daily Mail paid $2,000 for a Syrian passport, ID card and driver's license, purchased in Turkey.

A 38-year-old Syrian smuggler known as Malik al-Behar ("The King of the Shores") showed writers from the New Republic in Turkey a slew of fake Turkish, Syrian and European documents worth thousands of dollars.

And last year, a Vocativ reporter interviewed a black-market "merchant" selling fake Syrian passports on the Turkish-Syrian border. His going rate for a new passport: $1,800. The reporter met the unnamed passport peddler in a Turkish cafe:

[The merchant ] slaps a stack of passports on the table and begins showing me the different types of alterations: new photographs and names, clean visa pages and expiry date changes. He says he sometimes even buys old passports from desperate Syrians who have already made it safely to Turkey.

These passports aren’t technically fakes. According to the man, when rebels first took over the Syrian town of Azaz just across the border from government forces, they also “liberated” a passport printing office. Now he and his crew of brokers and smugglers have access to all of the equipment necessary to make new passports, or to alter existing ones. “Made in Germany,” he says of the printing machinery, smiling.

Earlier this year, a 27-year-old Algerian man named Hamza spoke to a Post reporter in Vienna, saying he and his mates were in Turkey when they "destroyed our passports and just mixed with the Syrian refugees." So the Germany-bound migrants began passing themselves off as Syrians.

“It’s really easy now to travel with these refugees," Hamza told The Post. "We received food and shelter, and a nice welcoming from people so far.”

The Frontex head, Leggeri, said in September that there hadn't been any evidence yet that potential terrorists were using fraudulent Syrian passports to enter Europe.

But the fear of militants using fake documents to enter Europe has become among the most pressing concerns of the refugee crisis.

“It is obvious now,” Bernard Squarcini, the former chief of French intelligence, told The Post's Anthony Faiola this week. “Amongst the migrants, there are some terrorists.”

The Paris assailants identified thus far were all European Union nationals. European countries have since agreed to bolster security measures along the continent's borders, including stricter passport controls.

Meanwhile, the identity of the stadium bomber with the fake Syrian passport remains a mystery.

French Prime Minister Manuel Valls told France 2 on Thursday that some of the Paris attackers "took advantage of the refugee crisis ... of the chaos, perhaps, for some of them to slip in."

© Washington Post