Life after Assad looks ominous for Syria's Christian minority

Not everyone is supporting the uprising against the country's brutal regime. Khalid Ali reports from Damascus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

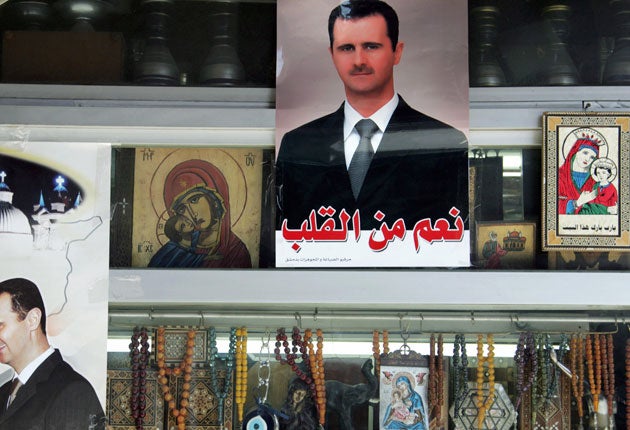

Your support makes all the difference.In the gift shop of Damascus' Chapel of Ananias, a middle-aged Christian man called Sari explained who he thought was to blame for the stories of government brutality emerging from his country.

"All the international media are liars," he said. "Al Jazeera, BBC, CNN – they are all lying. There is no trouble here in Damascus."

Syria's more than 2 million Christians account for around 10 per cent of the total population and are just one minority in patchwork of different creeds. But in interviews this week, some of them said many in their community were uneasy about the anti-government protests convulsing their country.

According to one activist called Yusef, who used to be an organiser for his local church in Damascus, many Christians have no great love for the Assad regime. Yet large numbers are worried about what will happen if he falls.

"Many of them are not getting any benefits from this government," said Yusef in his central Damascus living room. "On the other hand, they are not getting damaged. Some people are thinking, 'in the future, maybe I won't have the benefits but I will also be damaged as well'."

The reasons for their opposition to the protest movement are manifold, said Yusef. Some have lucrative jobs as a result of government connections, while others "simply believe what they watch on state TV".

There is also, he admits, a fear that Islam might usurp the secular – albeit repressive – brand of Baathist socialist rule in Syria.

"Right now Christians can celebrate Easter. They can wear whatever they want. They can go to the church in safety and they can drink if they want to.

"They are afraid they will lose all this if the regime falls down."

The Christians of Damascus are not alone in their anxiety about what a post-Assad state might look like. Many others living in and outside the capital – particularly the business elite whose fortunes are tied to the regime – have their own vested interest in protecting the regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

And according to one activist who spoke to The Independent, a Sunni Muslim called Houssam, the sentiments of Christians in places like the southern city of Deraa are markedly different to those living in Damascus.

"I have friends living there who are so angry about what has happened in their town," he explained.

Another Christian, a student in her twenties called Dima, dismissed the fears held by some of her friends about the threat of militant Islamism.

There is also a danger, she said, in trying to pigeonhole Syria's many different ethnicities and creeds.

One Alawite woman in Damascus, an artist in her thirties, explained why she was behind the uprising despite belonging to the same Shia sect as the Syrian President.

"The reason that so many people in my sect support him is because his father, the previous president Hafez al-Assad, exploited the Alawite people," she said.

"He made a huge point of saying the Muslim Brotherhood would kill every Alawite person. He put this in their heads forever."

Yet there is no denying that many in Syria's Christian community do not share the enthusiasm of the protest movement.

"One of my friend's brothers was saying how he beat up somebody who supported the demonstrations," said Dima. "Most of the people I know are not in favour of the uprising. They are very worried."

Names have been changed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments