Isis in Syria: The story of the martyred soldiers who fought 'to the last bullet' to avoid the fate of captured comrades beheaded by militants

Syrian forces have retaken 20 miles of territory in the north-east, inspired to fight to the death in some cases for fear of the consequences of capture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

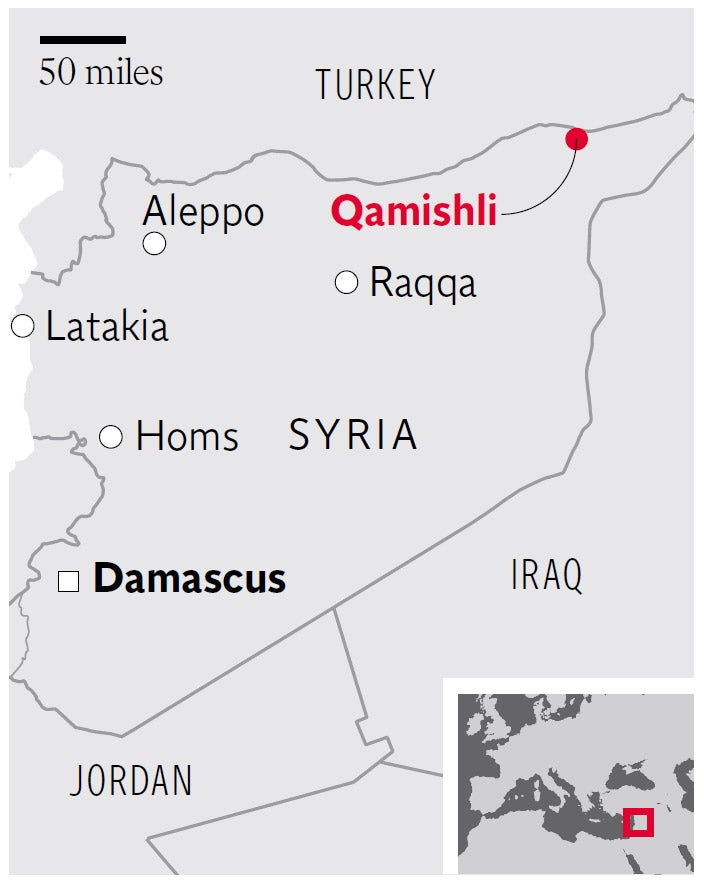

Your support makes all the difference.No one knows who Haj Badr was, but his white-painted tomb lies in a small sanctuary atop an ancient “tel” where potsherds thousands of years old lie scattered down the hillside. And it is from this windswept outpost south of Qamishli – for many years a cemetery for local villagers – that the soldiers of the Syrian 54th Special Forces Paratroop regiment watch the Isis front lines to the south, across mile after mile of wheat fields and tiny villages, whose mud and straw oval roofs look like miniature loaves of bread.

Over the past two months they have recaptured up to 20 miles of territory from their Islamist enemies. These are hard, ruthless men who take no prisoners and fight to the end. In the village of Hayahi, Special Forces Major Suied Basil el-Shawaa, along with seven soldiers and 10 members of the locally recruited “National Defence Force” militia, found themselves fighting dozens of Isis fighters who had surrounded them in a small house and demanded their surrender.

“They chose to fight on to the end, to their last bullet,” a general said outside the wreckage of the building. “All were martyred.”

These soldiers have seen the Isis videos of their captured comrades in other isolated outposts in Syria, and have watched their ferocious decapitation and execution by firing squad.

No wonder they fight to the end. But a journey across dozens of miles south of Haj Badr’s hilltop tomb proves that the Pentagon’s claim that the Syrian government doesn’t choose – or want – to fight Isis, is untrue.

The militiamen with them stand at checkpoints along the dirt roads; several have been kidnapped from their homes at night – one of them was taken to a neighbouring village where his head was sawn off – so this is a cruel war.

Since a directive came from Syria’s Prime Minister last week that no officers were to give interviews – even to Syrian newspapers – the men of the 54th regiment cannot speak “on the record”, but they all gave me their full names, ranks and home town and talked freely of the battles of the past four months.

When Mosul fell, they said, Isis began using advanced American weapons against these soldiers and started firing missiles with a 14km range right into the centre of Qamishli, in the north east on the Turkish border. That’s when the Syrian army decided to push Isis back from the fringes of the city and effectively put Qamishli – up to now, at least – out of range.

And they did so not with tanks but with artillery and scores of Japanese open trucks mounted with heavy machine guns – the very tactics which Isis used to such deadly effect against the Iraqi army outside Mosul. “Sometimes it’s a good idea to use the enemy’s tactics,” a colonel in the Syrian military intelligence service said.

Indeed, seven of these vehicles, soldiers standing behind fitted armoured shields above the driver’s cab, trailed behind me when I visited the front line far south of Qamishli. The soldiers here have been fitted out with new Russian camouflage combat helmets and showed me the new anti-tank weapons they have begun using: 9K115-2 Metis anti-armour missiles with a range of 2km – and manufactured, of course, in Russia.

Their most forward position is in an unfinished two-storey house where the soldiers sleep behind concrete blocks with a heavy machine gun on the roof and patrols along dozens of First World War-style earth trenches and revetments just in front of the building. When I asked the machine-gunner where Isis was, he pointed across a burnt field to a clump of trees perhaps half a mile away.

“They move all the time,” he said, “and we see their dust trails and if, from time to time, we see a truck we don’t like, we fire at it – and it doesn’t come back.” In the middle of no-man’s land, a farmer was bravely driving a tractor and plough.

But many of the fields are ashes. The Arab villagers, some of whom lived on under Isis occupation until the army retook the land – the women forced to stay inside their homes – say the Islamists freely took whatever food they wanted, including barley and vegetables, and carried sacks of wheat away. The wheat they could not take, they burnt. Most of the villagers have returned homes since the army arrived.

The military claims that in one operation four months ago, they captured 18 villages from Isis in 24 hours. But Isis can still penetrate these defences. A few hours before I arrived in Qamishli, a suicide bomber blew himself up outside a local Kurdish militia office, killing five of their fighters.

Nor did the Syrian colonel and general travelling with me take their enemies lightly. Repeatedly, the general told his men we were entering a “silence zone” in which no soldiers were permitted to use radios. He acknowledged that Isis must listen in, just as the Syrians can hear Isis communications.

“We often don’t understand them because they are foreigners speaking their own language,” the general said. When I asked him which language he heard most frequently, he replied. “Well, it’s very strange, but we think many of them are speaking in a language which is Chinese.” He was not joking.

And what, I asked, about those famous Isis black-and-white flags which we have all seen on the television pictures from the Kurdish town of Kobani – or Ain al-Arab in Arabic – far to the west of us? “Simple,” the general said. “Whenever they put a flag up, even for five minutes, I call in artillery fire and blow it to bits. They haven’t tried to raise a flag here for weeks.”

Sometimes – through villages with names like Rukaya and Atawarish, Jdeide and Hamera – clouds of grey smoke passed over us from the privately worked oil refineries to the east, or perhaps from Isis-run wells south of the front line. There were more military fortresses with more lines of trenches and I turned to the grey-haired intelligence colonel – himself wounded by shrapnel and his bodyguard killed in a recent attack on the road to Hassake – and asked if these trenches were prepared in case Isis tried a sudden mass attack. “They’ve done it before,” he said. “We know their tactics and they are not going to get past us.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments