Iran and the West: on the brink of a choice to trust again

With talks between the two sides ending next month, Rob Hastings sees the site of one of the nuclear plants used to enrich uranium

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shortly before it joins Freeway 7, the potholed tarmac of the road from Abyaneh towards Kashan passes alongside a low-rise complex of sandy-coloured buildings behind a wire fence more than a mile long.

Only the installations of anti-aircraft guns dotted among the dry tufts of desert grass, where some soldiers hang their washing out to dry beside the artillery batteries, hint at the controversial activities taking place inside.

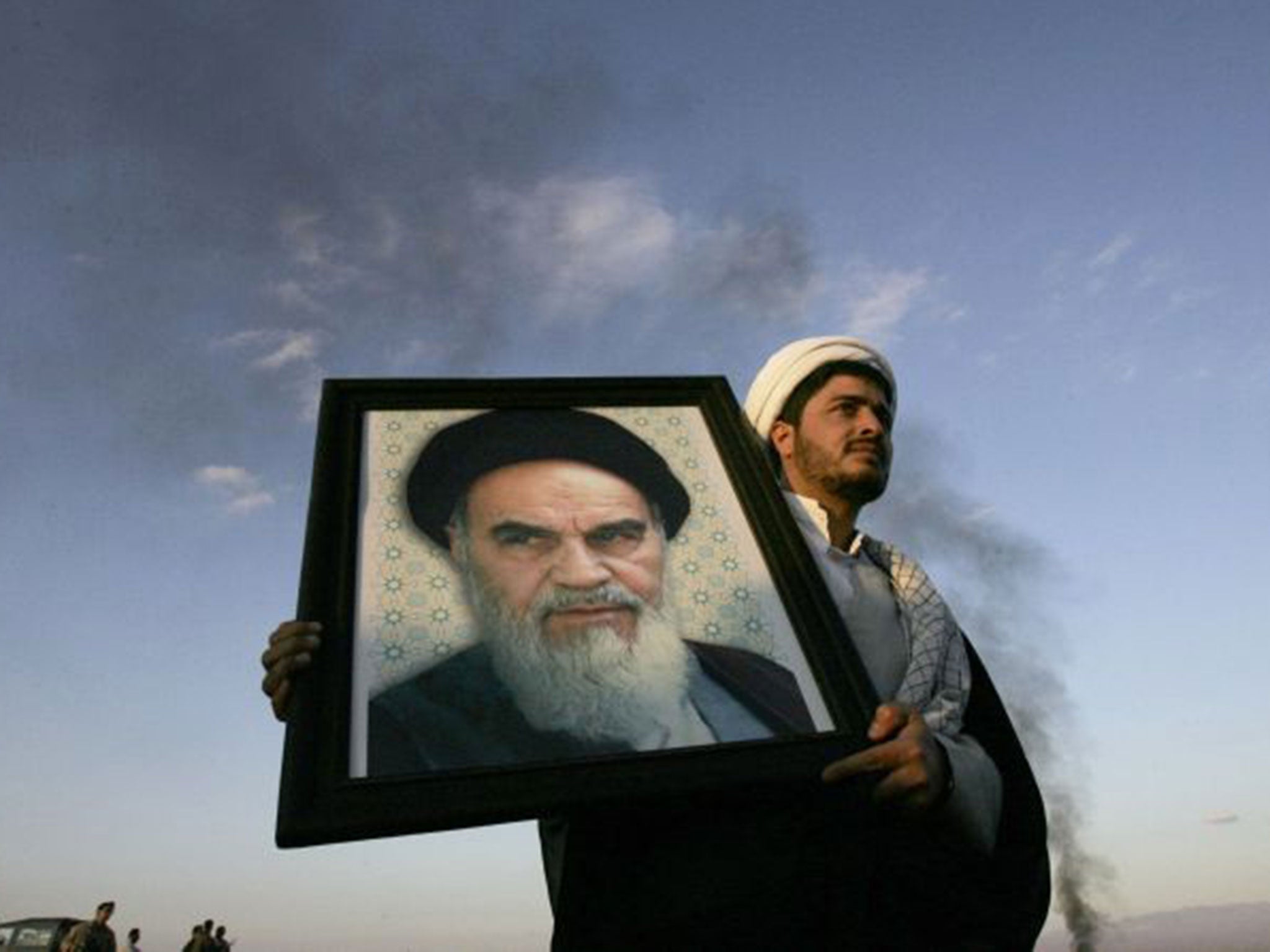

This is the Natanz uranium enrichment plant. Beyond the entrance arch, adorned by the obligatory icons of the Islamic Republic’s two revolutionary imams – Khomeini and Khamenei – Iranian scientists are producing nuclear fuel using thousands of centrifuges in underground laboratories.

According to the government in Tehran, they are doing nothing more than manufacturing fuel for the country’s Bushehr power station. The country regularly reminds the world that it holds an “inalienable right” to peaceful nuclear energy, like any other nation, under the terms of the non-proliferation treaty – and asserts that nuclear weapons would be against the Islamic law that underpins the country’s laws and ethos.

But suspicious Western leaders have long worried that Natanz could be the mainstay of a secret atomic weapons project. Some of the most hawkish politicians in Israel, still concerned that verbal threats to their country’s existence made by Iran’s former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad could literally go nuclear, want the site to be bombed.

It was inside Natanz that the Stuxnet computer virus, believed to have been worked on by the US and Israel, was reportedly used in 2010 to disable as many centrifuges as possible – and it is here that Iran claimed to have shot down an Israeli “stealth drone” just two months ago.

In short, this is the place most in the minds of international negotiators as they try to diffuse the nuclear crisis that has put the West and Iran at loggerheads for a decade.

Now, after years of sanctions to hold back Iran’s ambitions and punish its economy, talks in Vienna between Iran and representatives of the P5+1 nations – the officially nuclear-armed nations of Britain, China, France, Russia and the US, plus Germany – are reaching a climax. Iran is looking for acceptance of the thousands of centrifuges spinning in the labs of Natanz and elsewhere to produce enriched uranium which could be used for nuclear fuel. The US and its allies want to restrict their number and capability, to ensure the uranium is not enriched enough and in enough volume to be suitable for a nuclear weapon. Speaking last week, Wendy Sherman, Under Secretary for Political Affairs at the US State Department, said: “All the components of a plan that should be acceptable to both sides are on the table.”

As the mutually agreed 24 November deadline approaches, Iranians, tired of their country being treated as a pariah, are listening out for updates – hoping that a deal would allow them to begin rebuilding their economy.

Ask about their country’s atomic aspirations, and they say the government in Tehran is doing nothing wrong. “We do not need nuclear weapons, Iran covers a million square kilometres and could never be invaded – and, besides, our technology isn’t good enough to make a bomb,” Reza, a tourism worker, tells me in nearby Kashan. “We just need energy for the country’s future.”

The proximity of the Natanz site to an open road, just 100 metres or so away and frequented by travellers, seems to support his view.

To the tourists driving past the Natanz site on their journeys to and from the beautiful and ancient red-stone village of Abyaneh a few miles south, their Lonely Planet guides offer one piece of advice on the plant: “Do not, under any circumstances, take photographs of this – even from a car or bus”. But the fact that they can go anywhere near it might seem surprising. Given the way that it is reported in the West, it would be fair to imagine that it is miles from sight, in a huge exclusion zone deep inside one of the Iran’s two vast deserts.

However, Michael Axworthy, former head of the Iran Section at the British Foreign Office and author of Revolutionary Iran, who has himself seen the plant while driving en route from Esfahan to Tehran, says: “You should bear in mind that it’s part of a story which the Iranians are presenting, that all of this is a civil nuclear programme. There are other installations, like the one at Ferdows, which are in more remote locations – and, who knows, there may be ones we don’t know anything about at all.”

Inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency monitor activities at Natanz, and at other declared nuclear sites across the Islamic Republic, and say everything is above board. Yet, in their most recent report, the inspectors add that they “are not in a position to provide credible assurance about the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities in Iran, and therefore to conclude that all nuclear material in Iran is in peaceful activities”.

Dr Axworthy says that he does not question evidence that Iran held “an ambition towards a nuclear weapon programme” until 2003, but believes that it indicated a desire to be capable of building a bomb at short notice rather than actually to manufacture one – a capacity that would act as a deterrent to Israel and other rivals.

With Iranian and Western interests in the Middle East appearing to be increasingly aligned – in the fight against the extremist Sunni militia of Islamic State, as well as in the desire to achieve stability in Iraq and Afghanistan – it seems that now could be the perfect time to strike a deal. The election of President Hassan Rouhani, a relatively moderate figure who has led Iran’s nuclear negotiating team in the past, has also helped.

Jack Straw, the former foreign secretary who visited Iran earlier this year as part of a delegation exploring the possibility of exchanging ambassadors, told The IoS: “The risk of trusting the Rouhani government a little more, and reaching agreement, is far less than the risks inherent in not reaching a deal. No deal will not lead to a continuation of the status quo ... it will strengthen the negative forces opposed to any rapprochement with the international community.

“It was intransigence from hard-line elements of the US administration, pushed by the government of Israel, which led to the collapse of the last negotiations in 2005. Iran then had 200 centrifuges. By the time the negotiations resumed, following President Rouhani’s election in 2013, they had nearly 19,000 – and this despite tightened sanctions.”

It was with optimism at the possibilities of reaching a deal that David Cameron shook hands with President Rouhani last month, in the first meeting between leaders of the two countries since before the 1979 revolution. But many ordinary Iranians were angered by Mr Cameron’s later speech at the United Nations, which cited Iran’s “support for terrorist organisations” such as Hezbollah.

“He insulted us just two hours after meeting the President. There was no need, that is not politics,” says Hossein, a civil engineer in Esfahan.

The relationship has improved since the British embassy in Tehran was stormed in 2011. But there is still much to be done before the black lion and unicorn statues on the gate of the empty compound will welcome visitors again. And that could largely depend on what agreement can be reached on Natanz.

The names of Reza and Hossein have been changed

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments