Despite regional conflict, Lebanon is planning to become a railway powerhouse once again

Amid regional uncertainty Beirut has the chance to revive its steam-age role as a key transit hub

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lebanon as a rail powerhouse for the rebuilding of post-war Syria, high-speed double-track trains running in tunnels through the Lebanese mountains above Beirut, sidings for the building-blocks of Syria’s new cities in the Bekaa Valley – do not think here, dear reader, of the Roman temples of Baalbek – and a link up with the great railways that will run from the Gulf to Europe via the new Iraq and the new Syria. Why, even pipelines may run alongside the tracks.

The Lebanese dream dreams. But in Beirut they also suffer some of the Middle East’s most titanic traffic jams. Why not an electric rail between the northern city of Tripoli and Tyre in the far south? With Beirut Central Station built, as was once planned by the French after Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war, beneath the Virgin Megastore at one end of Martyrs’ Square? With its mountains, Roman ruins, crusader castles, snow and beaches but with a hopeless sectarian system of government, Lebanon may be a Rolls-Royce with square wheels but it could at least have trains.

Of course, the first steam loco chugged across the mountains to Damascus 120 years ago. This week the auditorium of the Unesco palace in Beirut echoed to the hoots and wails of French 0-8-0 steamers and Swiss rack-and-pinion trains as they huffed and puffed their way on film to Tripoli, Homs and through the snow-blanketed heights of Dahr el-Baidur to the Bekaa and Syria. Up to 800 young NGOs and civil servants – an extraordinary number for a bleak, rainy weeknight in Beirut – applauded the new putative age of Lebanese rail.

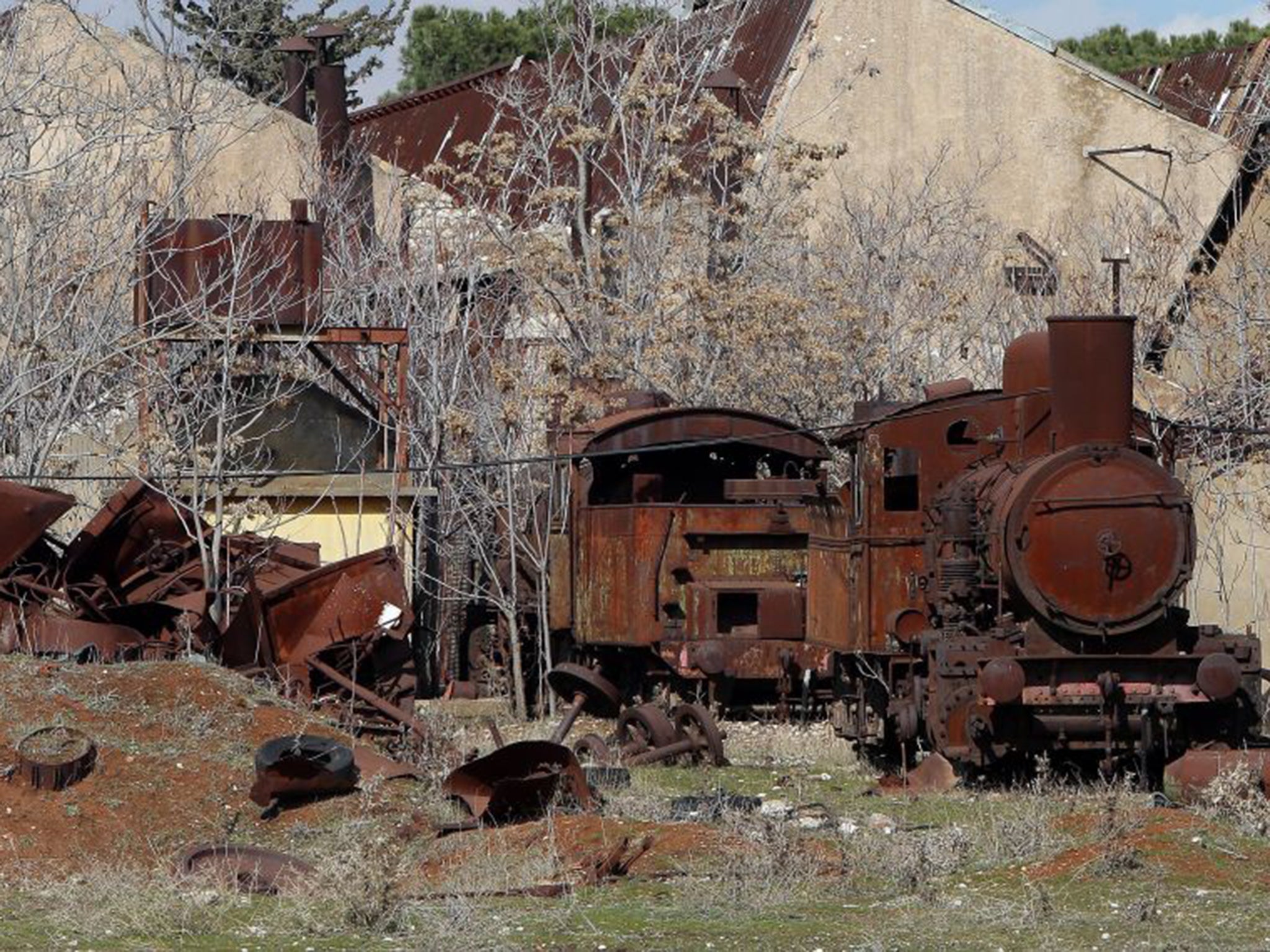

Pity it doesn’t exist – yet. But could it? Every photographer, filmmaker and reporter has made their pilgrimage to the rusted tank engines and broken carriages and delicate French cut-stone railway stations that still litter Lebanon. There are coffee-table books about the country’s railway heritage, from the Swiss Winterthur locomotives that the Ottomans brought to Lebanon in 1895 to climb its mountains, to the big French Cail engines that still rot in the old railway marshalling yard at Tripoli, their oil bleeding – even to this day – onto the old tracks, onto the bushes and the pink flowers embracing the drivers’ cabs.

So there was something rejuvenating about the speakers who introduced Zeina Haddad’s painstaking documentary on Lebanon’s old railways. A German diplomat extolled the international background of the railways and proudly announced that the big G-8 loco on the poster for the accompanying exhibition was manufactured in Germany. Alas, he diplomatically avoided mentioning that these particular engines were 1919 war reparations handed over by the Kaiser’s Germany to France after the First World War and then shipped by the French victors to their Lebanese mandate.

Eugene Sensenig-Dabbous, an Austrian politics professor at Notre Dame University in Lebanon and engineer by profession, told his Unesco audience that “railways are a regional, international issue because infrastructure development is one of the keys to the future of the Middle East”.

Talking later, he was more specific. “The majority of the freight for re-launching Syria after the war will obviously go through Beirut. The Syrian port of Lattakia is too small. The reopening of the old Tripoli-Homs train line, which is still relatively intact, could be done quite quickly.

“But the Gulf states are now investing tens of millions of dollars on rail lines that are supposed to go through Iraq and Syria. The Lebanese railways can be linked to this – or be separated from the rest of the world. There could be a tunnel from Baabdat [above Beirut] to Chtaura, right through the mountains. We already have proposals from international corporations who would do this at their own expense. If there were lines from the Gulf states to Europe, there could be a tunnel from Beirut to a transit ‘harbour’ in the Bekaa. Material would go from Beirut to the Bekaa and the line would go on to Syria, the Gulf and Europe.”

At least 40 Lebanese NGOs have been working on the environmental impact of the tunnels – a huge amount of ground water would flow down the mountains to Beirut. “The entire network in Lebanon has to be replaced,” Mr Sensenig-Dabbous said. “We could have a ‘nostalgia’ steam train running from Byblos north to Batroun that could be a huge tourist attraction. But the purpose of our work is to let the Lebanese people know that there were trains here. This is where we are now. People are stealing stuff from the railroad yards and they are destroying the tracks from Beirut to Damascus. We are getting entire schools to ‘adopt’ a railway station. We must reintegrate railways into the region and ensure the future of sustainable transportation. Natural-gas pipes and rails can run alongside each other. It will be a very ‘disciplining’ experience. The railways of Europe ‘disciplined’ the people.”

The head of NGO Train-Train is a dogged Ecuador-born Lebanese filmmaker called Elias Maalouf – yes, he is a distant relative of that brilliant Lebanese-French novelist Amin Maalouf – who has lived, breathed and talked trains since the Syrian army stopped him filming their destruction of railway archives at Rayak in 2005. He lives with a sad-eyed Labrador named Elvis and a parrot called Kiwi, and his home above Byblos is festooned with oil paintings depicting stations and locomotives. His business card, of course, sports a photograph of a veteran Lebanese steam locomotive hauling trucks out of Beirut.

But “corruption” is the most common word in his vocabulary, and it is not difficult to see why. During and after the Lebanese civil war, houses were built on top of the permanent way, trains were sold off for scrap and kilometres of track looted and sold. Where did the money go? Since the railways in Lebanon are government-owned and their invaluable property belongs to the state, just who made the profits? Would government archives reveal this? It’s not surprising, then, that the Lebanese authorities have shown no great love for Train-Train or for Elias Maalouf, who has been officially forbidden from entering the wrecked old central station of Beirut.

So Mr Maalouf is partly relying on the sheer frustration of the automobile-intoxicated Lebanese to bring back the trains. “We need the political will and everyone is stuck in the traffic,” he said. “The president cannot drive without being stuck in the traffic. Nor can the prime minister. Forty-two per cent of all pollutants in Beirut come from cars. I am not interested in all this political ‘thing’. I don’t believe in borders. I believe in trains.”

According to Mr Maalouf, less than five per cent of railway land has been “encroached”, illegally or “legally” but “if you don’t preserve it, it will go”. He believes that the current tracks should be turned into UN heritage sites in order to protect them. He even has an ingenious plan to take over the front pages of the Lebanese press when the country celebrates the 120th anniversary of its first steam train this August.

“We’re building big replicas of the first locomotive and its carriages and we’re going to have the old steam-train drivers and crews push the train on wheels from outside what was the central station all the way to the parliament building,” he said. “And there the engine will become a permanent exhibit.”

In a country without a president and a functioning government, small gestures become revolutionary acts. Barring bureaucracy. And corruption. And the continuation of the Syrian war.