David Cameron’s ‘free Libya’ is no-go area, Foreign Office says

Despite the spectre of Isis making greater inroads, the PM says he does not regret helping to get rid of Gaddafi

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wearing ties, they both looked a little stuffy as they visited injured rebel soldiers in Tripoli, but the message was simple: we have saved you.

Later that day, David Cameron, fresh from his first and apparently successful foreign military intervention, took the stage at a Benghazi rally, alongside Nicolas Sarkozy. “It is great to be here in free Benghazi, and free Libya,” he said.

“Your city was an inspiration to the world as you threw off the dictator and chose freedom. People in Britain salute your courage.”

That was September 2011. A month earlier, Libyan militiamen had killed Muammar Gaddafi in his home city of Sirte. By then the dictator was a busted flush: coalition air strikes had muted his attempts to squash the Libyan chapter of the Arab uprising and anti-regime fighters were routing his forces. Until Britain, France and a handful of others intervened, with UN backing, Libyans opposed to Gaddafi were being slaughtered.

Philip Hammond, then the UK’s new Defence Secretary, urged British businessmen to get ahead in the expected rush to cash in on Libya’s reconstruction and vast oil industry. It was time for British companies to be “packing their suitcases and looking to get out to Libya... as soon as they can”, he said.

Now that he is Foreign Secretary, Mr Hammond’s department’s advice is somewhat less ebullient. “The Foreign and Commonwealth Office advise against all travel to Libya due to the ongoing fighting and deteriorating security situation... The British Embassy in Tripoli has temporarily closed, and is unable to provide consular assistance. There is a high threat from terrorism.”

Speaking in Hove yesterday, the Prime Minister defended his intervention. “Do I regret that Britain played our role in getting rid of Gaddafi and coming to the aid of that nation when Gaddafi was going to murder his own citizens in Benghazi? No I don’t...

“Libya, Britain and the world are better off without Gaddafi, but we have to do as much as we can now with, I hope, a willing Libyan population and politicians to try and bring that national-unity government together – but it has been very hard work.”

Last weekend, Isis attacked Sirte. Its beheading of 21 Egyptian Copts on a beach nearby sent a message that it had seized control – as it has in Derna, near the eastern border with Egypt. Its growing presence will panic Western leaders: Italy has threatened military action, and after bombing targets near Derna on Monday, Egypt called for an international coalition to flush Isis out of Libya.

The UN Security Council will meet in emergency session tonight. Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said: “We will not allow them to cut off the heads of our children… What happened is a crime, a monstrous terrorist crime.”

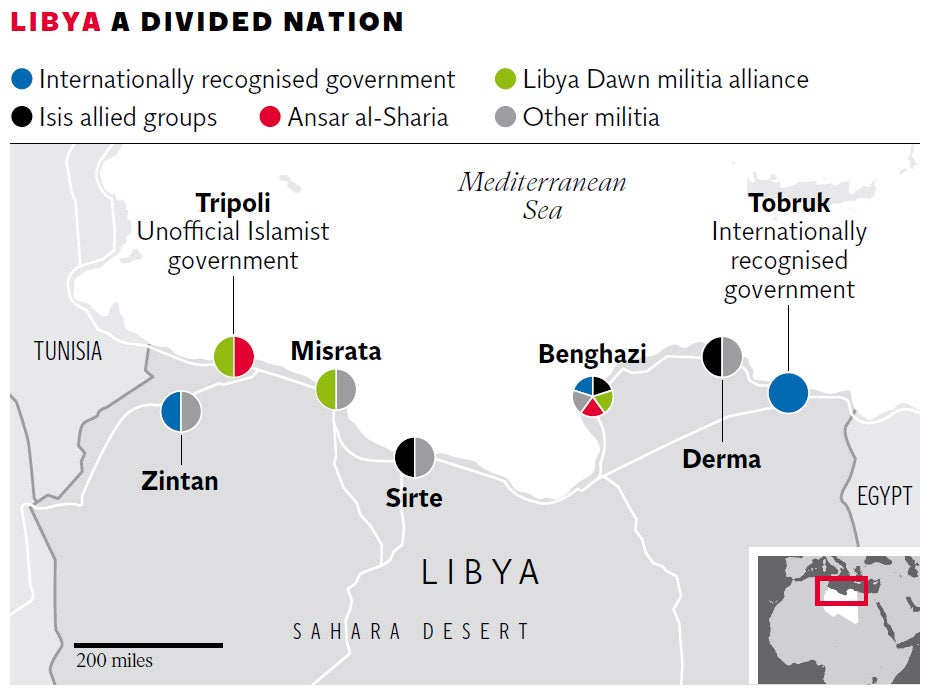

But Libya has other problems, including two competing administrations. In Tripoli, an Islamist government inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood, condemned Egypt’s air strikes, while 600 miles east, in Tobruk, the internationally recognised government praised the Egyptian action, and sent its warplanes to join it.

High-profile terror attacks, such as the one in Benghazi in 2012 that killed the US ambassador Christopher Stevens, have captured headlines. That was perpetrated by Ansar al-Sharia, an Islamist group that wants sharia law to be implemented in Libya. But Libya has been wrought by violence ever since Gaddafi’s ouster. There is a plethora of independent militia.

General Khalifa Haftar leads the Libyan National Army, a force loyal to the Tobruk-based government. “My basic task is to cleanse Libya of the Muslim Brotherhood,” he said last month.

Libya Dawn is an Islamist group, which helped to install the rival government in Tripoli. But it, too, is concerned about the rise of Isis-backed groups and says it is battling terrorism in the country.

The UN is hosting peace talks in Geneva, and while most sides have agreed to continue talking, Libya Dawn has refused to take part. Optimists believe that Sirte’s capture by Isis could bring competing groups together against their common enemy.

However, Mr al-Sisi is unlikely to win UN support for more intervention in Libya, and some suspect Egypt does not have the resources needed for a prolonged offensive.

Equally, the blame cannot entirely be left at the West’s door. It eventually chose not to unseat Bashar al-Assad, and Isis came to Syria anyway. But Mr Cameron’s claim that Libya is free now looks far‑fetched.

It is difficult to imagine him going back any time soon, especially if he follows the Foreign Office’s advice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments