What now for Europe? The EU's Irish problem

Ireland's rejection of the Lisbon Treaty raises fears of a constitutional crisis – and could lead to a two-tier union of nations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Irish Republic woke up yesterday with a severe collective political hangover, in the wake of the voters' rejection of the EU's Lisbon Treaty. Neither Dublin nor Europe as a whole appears to have a clear idea of how to proceed, following the referendum result which has changed the European landscape.

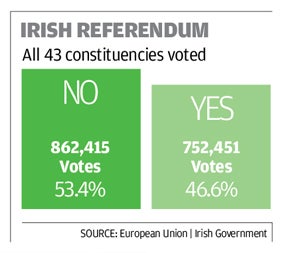

With France about to take up the European presidency, the dominant item on the agenda is how to prevent the Lisbon impasse developing into a full-blown crisis after Ireland voted 53.4 per cent to 46.6 per cent against the treaty.

Most of the EU's 27 countries have already ratified the Lisbon Treaty, and opinion in London, Paris, Brussels and elsewhere clearly favours continuing with this process. But even as the ratifications continue, the EU and Dublin will have to work out how to cope with the problem posed by the Irish rejection.

Downing Street made clear yesterday that it would press ahead with ratifying the treaty in Parliament, with the Lords to vote for the final time on Wednesday before it reaches the statute books.

The Minister for Europe, Jim Murphy, said it was now up to the Dublin government to find a way forward. He insisted that the vote in Ireland did not mean the treaty was dead. "Only those who previously wished to dance on the grave of this treaty, even before the Irish referendum, are declaring it dead," he told Radio 4's Today programme.

A Downing Street spokesman said: "The position is that each country has its own process for ratification ... It is not for us to tell the Irish what to do."

With no appetite for any wholesale renegotiation of the treaty, as was advocated by anti-Lisbon campaigners during the referendum, one alternative is to stage a rerun of the campaign. Ireland's Prime Minister, Brian Cowen, will face pressure for this when he attends a summit in Brussels this week. It is likely to prove a highly uncomfortable occasion for Mr Cowen, who took office just a few weeks ago. The referendum result is a significant early setback for him, seen in Dublin as a humiliation undermining his authority.

He campaigned vigorously for the treaty, but is thought to have made a personal blunder when he admitted that he had not read the lengthy treaty document from cover to cover.

Mr Cowen will probably be reluctant to contemplate a repeat of the referendum, although this was done some years ago when the Irish electorate first rejected a previous treaty but later accepted it.

Speaking on Irish television, Mr Cowen did not absolutely rule out a rerun. But yesterday Conor Lenihan, minister of state with responsibility for integration, described another referendum as unlikely, declaring: "It would create a double risk of creating even more damage.''

Referendum campaigns in Ireland are highly unpredictable and subject to personality factors and sudden swings. But in addition, there is a distinct disconnect between Irish voters and the current EU; and it is clear voters have many reservations, both on specific issues and on the general trend. In addition, there is a further disconnect between voters and the major Irish political parties, all of whom campaigned for a "Yes" vote.

The "No" sentiment is clearly running strongly in Ireland, and a second contest would be highly likely to produce yet another negative outcome – which would be even more unwelcome for Europe than the present situation and such a reverse for the authorities that the Irish government might well fall. This would clearly be an exercise for the very highest of stakes.

But the alternative could be severely damaging for Ireland as a nation, since it could involve major powers such as France and Germany in effect demoting the country's treasured status in Europe. This option would involve the creation of a two-tier EU, with Ireland becoming a marginalised and semi-detached member of the union.

Both courses, at their starkest, amount to almost doomsday scenarios for Ireland. The European Commission President, José Manuel Barroso, has declared: "I believe we should now try to find a solution."

Q&A

So how did the Irish, model Europeans, come to reject the Lisbon Treaty?

There has always been an anti-European minority in the Irish Republic, though the big parties are all fervently in favour. But the days of huge amounts of money coming from Europe to transform the country from poverty to prosperity are over. And the Irish trust their politicians much less these days.

Haven't the Irish done well out of Europe?

Certainly. It's reckoned they've benefited to the tune of more than €30bn (£25bn) since the 1970s. Ireland has been given a place on the world stage and allowed to emerge from the UK's economic shadow.

So are the Irish now anti-Europe?

Not at all. Almost all the prominent "No" campaigners, however strongly they were against Lisbon, described themselves as pro-European. But Brussels has come to seem more remote, and the Lisbon Treaty had – or was said to have – profound implications for some issues that are particularly neuralgic for the Irish.

Such as?

Abortion, Irish neutrality and possible conscription to a future European army, for example. The "No" campaigners were accused of scaremongering about these. Added to these specific issues was an underlying apprehension that Lisbon would reduce Irish influence in the EU.

Was the result a surprise?

Yes. Almost everyone thought the outcome would be closer. Most believed the "Yes" camp would scrape home. Instead, the Irish establishment has been left shocked by the result and remains flummoxed that its advice to voters was rejected.

So what happens next?

Nobody knows. Many European governments are seriously annoyed by the Irish failure to deliver on Lisbon. Some in Europe will call for a rerun of the referendum, while others favour bypassing the Irish and reducing their European influence. Months of debate and bargaining lie ahead.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments