The $35 billion problem worrying Vladimir Putin much more than Ukrainian sanctions

A recent ceasefire already looks set to crumble as fighting continues and Russia and Ukraine quibble over details of the agreement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Ukrainian ceasefire, tortuously reached over the past few days, already looks in danger of collapsing as reports emerge of continued fighting in the east of the country.

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, who was present at the talks, has warned EU leaders to prepare further sanctions against Russia should the ceasefire breakdown yet again.

But the Ukrainian situation may be the least of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s problems.

The Russian leader today announced a $35 billion anti-crisis spending plan, but admitted to reporters he did not know how best to implement the cash injection into the economy, a local Russian news station reported.

The economy aside, Russia faces its own threat from Islamic extremism, weak national institutions, increasing societal pressures, and looming unemployment.

1. Economic failings

Western economic sanctions are – undoubtedly – having an adverse effect on the Russian economy. But they are not the whole story, and many businesses are still finding loopholes to circumvent them – as this Economist article demonstrates.

Joseph Dayan, Head of Markets at BCS Financial Group, Russia’s largest broker, told The Independent it was “misleading” to point to sanctions as being the chief economic problem in Russia but added: “The country is going into a crippling recession this year”.

“50 per cent of the Russian government’s income is derived from what you can take from the ground - oil and gas - and today oil is doing better but it is this huge dependency that is the main factor impacting the Russian economy.”

Mr Dayan continued: “In good times this is a plus, but in bad times it is a burden.”

“But they can survive under a year or two, even under sanctions, as long as oil prices do not dip below $50,” he said. If that happens, “it could all end very badly,” Mr Dayan claimed.

2. Weak institutions

Russia is ranked as among the most corrupt nations on the planet, scoring just 27 out of 100 (0: highly corrupt, 100: clean) in Transparency Internationals 2014 ranking. It came below countries such as Pakistan, Gambia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria.

What this corruption translates to (returning to the economy) is that since the Russian government slid back reforms – for example, re-taking many of the businesses that were privatised during the boom years – productivity and investment have slumped.

Put simply: there is no growth as a direct result of corruption. Previous sources of growth have been exhausted and investment requires protection of property right and enforcement of contracts – exactly what corruption dissuades.

3. Unemployment

Last month the first deputy prime minister warned Russians to expect a rise in unemployment.

Figures showed an eight-month high in December, just months after reaching a record low in August last year.

One of Mr Putin’s signature achievements has been to keep unemployment falling since 2000, should this slip he may begin to feel the pressure internally.

4. Societal pressures

Two factors are important to remember here: firstly the turbulence of the economy; and secondly President Putin’s crackdown on social freedoms.

This crackdown, often targeting certain groups such as the LGBT community or press freedoms, has fuelled a wave of middle-class migration.

In 2013 more than 186,000 people left Russia. To put that in perspective, that’s five times as many as two years earlier according to state statistics agency figures quoted by business magazine Sekret Firmy.

Around 40,000 Russians applied for asylum in 2013, according to a UN report, 76 per cent more than in the previous year.

Added to these departures is Russia’s falling population. According to a recently published article by Yale Global the country’s shrinking population “is the result of deaths outnumbering births for nearly two decades without sufficient immigration to compensate for the deficit.”

5. Threat from Islamic extremism

Last month a senior Russian diplomat claimed that more than 800 Russian nationals were fighting alongside Isis, also known as the Islamic State. New York security firm Soufan Group claims the number is nearer 2,000.

Russia is grappling with similar problems to that of Europe – namely rising nationalism and xenophobia, which pushes selected groups towards extremism.

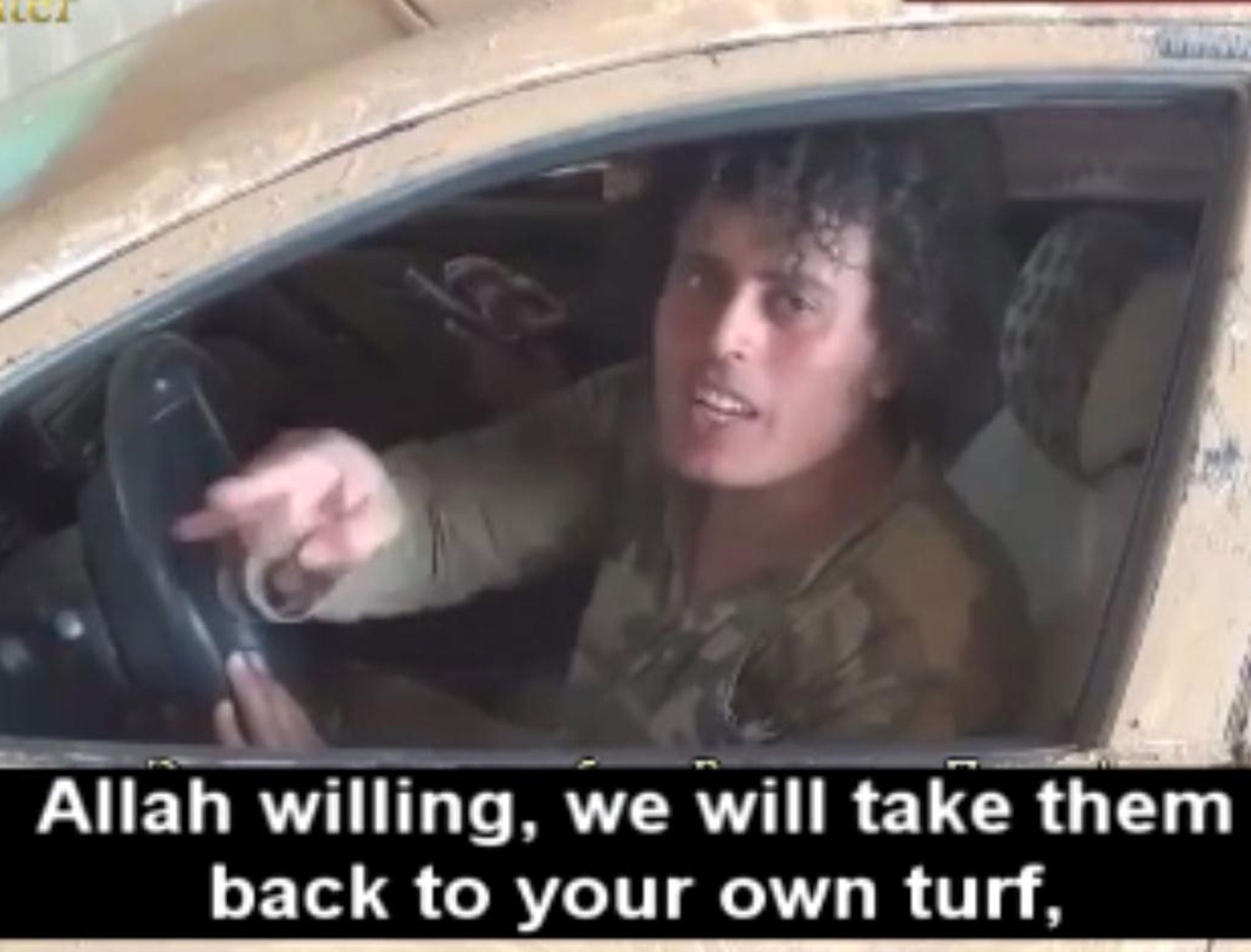

Many of those allegedly fighting were from the Northern Caucasus Chechen province and an Isis video in August threatened to bring the war home. "We will liberate Chechnya and the Caucasus, Allah willing,” said one fighter in the video.

This area has already seen two separatist wars but had stabilised in recent years under Moscow, after a brief-lived Islamic uprising in 1999. Mr Putin, prime minster at the time, quickly crushed the rebellion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments