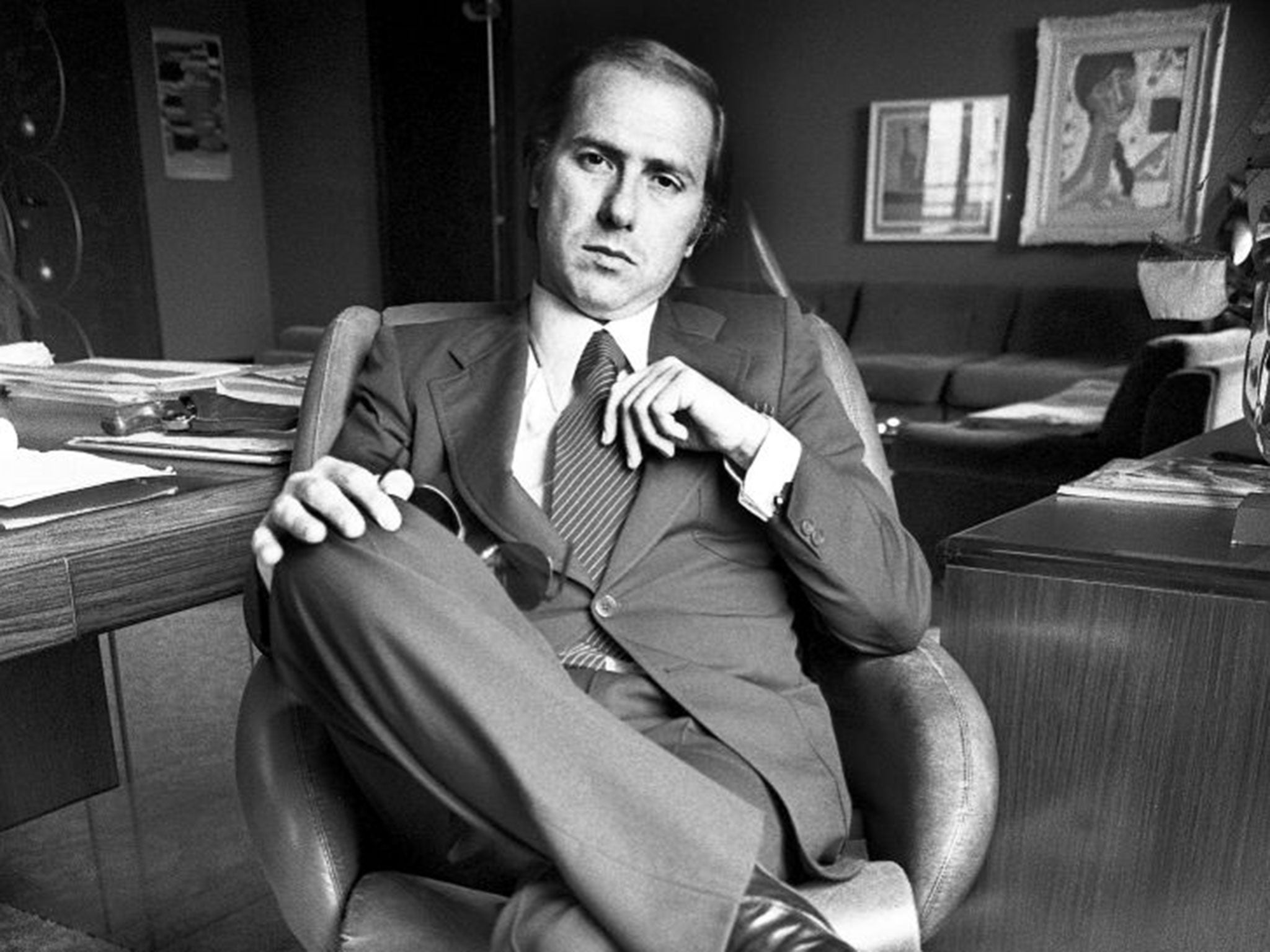

Silvio Berlusconi's links with Italian organised crime confirmed

Former Prime Minister’s involvement with Sicilian mafia is proven as his middle-man to Cosa Nostra arrested

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Silvio Berlusconi – Italy’s former Prime Minister and one of the world’s most recognisable politicians – did business with the mafia for nearly two decades.

That is the conclusion of the country’s Supreme Court of Cassation in Rome. The billionaire tycoon, nicknamed the Teflon Don, worked with Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, via his conduit and former senator Marcello Dell’Utri after judges sentenced Dell’Utri to seven years for mafia association.

Three-time premier Berlusconi, 77, has always denied rumours that mob links were behind the large and opaquely sourced investments used to kickstart his construction and media businesses in the 1970s and 1980s.

But Supreme Court judges accepted prosecutor Aurelio Galasso’s claim that “for 18 years, from 1974 to 1992, Marcello Dell’Utri was the guarantor of the agreement between Berlusconi and Cosa Nostra”. The verdict confirms the sentence imposed on 72-year-old Dell’Utri by Palermo’s Court of Appeal in March last year.

“In that period of time we’re talking about a continuous crime,” said Mr Galasso. He said the deal between the mafia and Berlusconi, mediated by Dell’Utri, was formed in 1974 and “was implemented voluntarily and knowingly”.

Berlusconi yesterday attacked “biased” judges. “[The rulings] are what the left has tried to do to me since ‘94,” he told Ansa news agency.

Giuseppe Di Peri, the lawyer for Dell’Utri who has always denied mob links, said his client would appeal to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

Berlusconi’s lawyers made similar noises following the tycoon’s conviction last August for tax fraud, but did not get very far with appeals to the European courts. The confirmation of Berlusconi’s long-suspected link to organised crime comes as he begins nine months of community service for the tax crime.

Berlusconi will not be tried for his links to the mob, however, because the statute of limitations for mafia-related offences kicks in after 20 years. But following a legal war lasting two decades, prosecutors have finally claimed the scalp of Dell’Utri, just before the statute could save him.

Around 40 former mafia members have given evidence that the Palermo-born politician and businessman was Berlusconi’s key emissary with Cosa Nostra. One high-profile informant, Giovanni “The Pig” Brusca, told judges in Palermo in 2010 that Berlusconi poured as much as 600 million old lire a year (£300,000) into Cosa Nostra’s coffers, which was “tied to his business activities in Sicily”.

As far back as 1974, Dell’Utri hired the Cosa Nostra figure Vittorio Mangano to work as the “stable master” in Berlusconi’s Arcore villa. It is widely believed that Mangano’s presence was to deter other criminal groups from kidnapping the mogul’s children, and that Berlusconi chose – or was obliged – to launder millions of pounds of mob money.

The authorities became aware that the gangster Mangano was working at the mogul’s Arcore mansion after the attempted abduction of one of Berlusconi’s dinner guests, an episode that was linked to the mafioso.

Both the mogul and Dell’Utri claimed they had had no idea who Mangano was. Berlusconi said during his 1994 election campaign that he fired Mangano after the bungled kidnapping. But when police arrived almost three weeks later he was still there. He also returned to Berlusconi’s mansion after a month in prison. Five years later, police tapping into Mangano’s phone calls during his stay at a Milan hotel recorded several conversations he had with Dell’Utri.

The telephone surveillance was designed to keep track of Mangano’s activity as the Cosa Nostra’s “bridgehead in the north of Italy”, according to the Palermo prosecutor Paolo Borsellino, who would later be killed by a mafia bomb.

Mangano was suspected of organising heroine shipments and laundering the cash in Milan’s financial community.

Prosecutors later probing Dell’Utri’s connections with Cosa Nostra even found a note in his diary recording how the mobster paid him a visit in Milan in 1993, while he was busy organising Berlusconi’s first general election campaign – this despite it being public knowledge that Mangano had been sent to prison by then magistrate Borsellino for much of the 1980s.

Dell’Utri, who was then head of Berlusconi’s multi-million pound TV advertising empire Publitalia, later went on to become a senator for his Forza Italia party.

Now, following his conviction, Italian authorities will seek Dell’Utri’s extradition from Lebanon, where he fled last month before the Supreme Court ruled on his fate. Interpol agents arrested him in a five-star hotel in Beirut with €30,000 (£24,500) in cash, days after Italian authorities sounded the alarm.

In a statement issued through his lawyer, Giuseppe Di Peri, Dell’Utri denied he’d fled justice. Judges in Palermo, however, declared that so much cash and 50 kilos of luggage beside amounted to evidence of a “planned and deliberate desire to flee justice”.

It was reported that Dell’Utri had been making use of his time abroad to arrange business deals involving the investment of millions of euros of Berlusconi’s money.

The pair appear loyal to each other and are prepared take their shared secrets to the grave. Dell’Utri is also one of the select few non-Berlusconi family members assigned a spot in the tycoon’s elaborate Arcore mausoleum.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments