Rout of the soft left: Europe veers right to beat recession

Angry voters stayed home in record numbers but did not flock to extremists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It may be difficult to say who "won" the European elections, but it is clear who lost. From France to Poland – and spectacularly in Britain – politicians of the moderate left were shunned or humiliated by the few voters who bothered to cast their ballots.

In a time of recession – and especially one caused by the exuberance and immoderate greed of markets – centre-left arguments might have been expected to thrive. Instead, centre-left parties of government were routed in Britain and soundly defeated in Portugal and narrowly beaten in Spain. Centre-left opposition parties were rejected in Italy and Poland and crushed in France. In Germany, where the main centre-right and centre-left parties share power, voters rejected the Social Democrats and gave a comfortable victory to Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian Democrats.

The principal exceptions to the rout of the moderate left were the good results for social democratic parties in Denmark, Sweden, Greece and Slovakia.

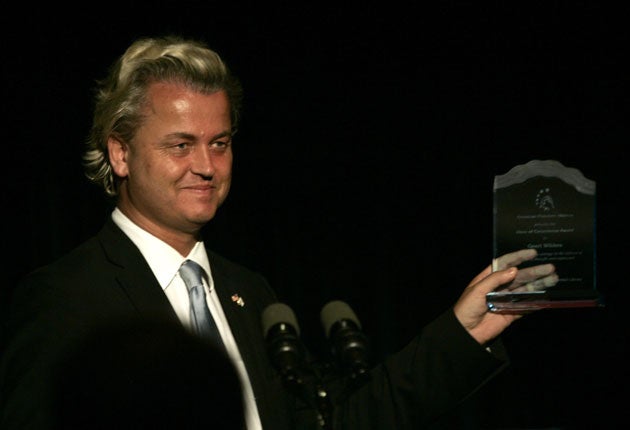

Elsewhere, some of the votes that might normally have gone to moderate left-wing parties migrated to the extremes of left and right. But, despite predictions of a Euro-festival of the far out, it was a mixed election for nationalists and populists. Extreme and racist parties did well in Britain, Hungary, the Netherlands and Austria, but the once powerful National Front lost half its seats in France and the most xenophobic Flemish nationalist party had its worst election in decades in Belgium.

Early analysis of the miserly turnout – just over 43 per cent across the EU – suggests centre-left parties have one possible alibi. It was the working and lower middle classes who most shunned the polling booths. So the elections were hopelessly skewed towards the comfortable and the well-off.

This may explain the apparent paradox of the results in France. President Nicolas Sarkozy is struggling in the opinion polls but his centre-right party, the Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP) scored a comfortable victory on Sunday with 28 per cent of the vote and 29 out of the 72 seats.

A delighted President Sarkozy claimed an endorsement for his programme of reform but, arguably, the result was not all that convincing.

On the face of it, the power balance in the European Parliament will not be radically altered when the new MEPs convene next week. The centre-right European People's Party group will still be in the majority followed by the Socialists and Liberal groups. Yet the cosy tradition of consensus politics between the two main groups has been shaken by losses for the Socialists group and the arrivals from dozens of new parties that will not fit into the mainstream blocs.

The total of "others" – mostly extremist nationalists who do not fit into groups – will rise from 30 to 90. The big unknown is how, for example, Jobbik, an openly anti-Semitic Hungarian party and a ragtag bunch of others will club together. Rules for political groups require at least 25 members drawn from a minimum of seven EU member states, and being part of a group is important in terms of power, as it entitles members to funding, offices, and, crucially, the right to vote in committees which are the nerve-centre of the parliament.

"There might be tectonic shifts, but it is very hard to predict what kind of parties will emerge", said Jacki Davis, of the European Policy Centre think tank. "We like to portray all these groups as 'nasties' but they all have very clear and distinctive agendas."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments