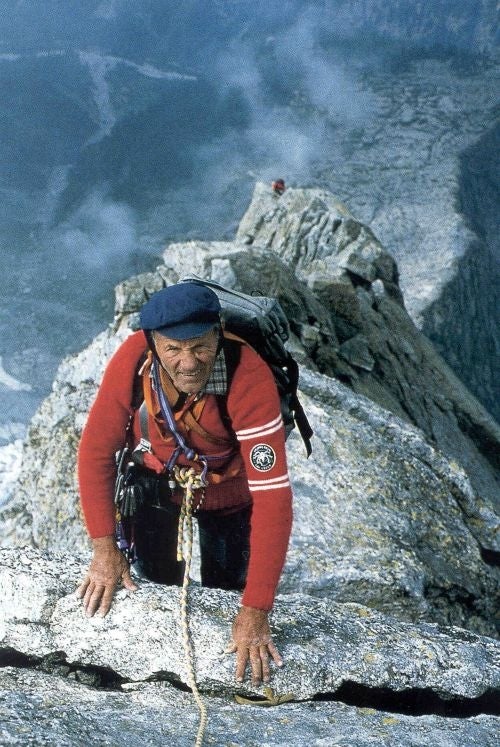

Riccardo Cassin: A climber who leads them all

Italy's Riccardo Cassin turns 100 next month, and the mountaineering world is preparing to honoura true pioneer. Peter Popham reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The trophies and honours are piling up in his home, but the best memorials to the life of Riccardo Cassin, who turns 100 on 2 January, are the soaring lines on mountain maps which show the way up the many dizzying peaks which he was the first man in the world to work out how to climb.

"Riccardo Cassin had figured out the way forward at this point," writes contemporary climber Jocelyn Chavy in his log of climbing the north-east face of a stunning lump of Alpine granite known as Piz Badile. "There are no other cracks, no alternative corners as distinct as the ones ... right in the centre of the face. How did they do it? No bolts, no climbing shoes. Just sheer willpower and lots of audacity: the will to invent and follow their route right to the apex of this gigantic funnel. The Badile is a gift to the present from the climbers of the Thirties, a masterpiece of modern climbing".

These days, Italy's most celebrated living climber gets around in a wheelchair, and he has been down with influenza for the past week, so an event scheduled for yesterday afternoon, in which he was due to receive an award from the mayor of Lecco, his home town on the edge of Lake Como, had to be postponed. Yet only five years ago, he was still following his daily regimen of push-ups and sit-ups, and he was climbing mountains deep into his eighties.

"His temperature has come down," said his grand-daughter Marta Cassin, 31, "and he's feeling much better but we didn't want to risk him getting flu again. Mentally, he's in good shape, he talks a lot and has many memories. As his birthday approaches, lots of old friends have been coming over to see him. Reinhold Messner was here a couple of weeks ago with Walter Bonatti, they ate together and stayed all afternoon talking about the climbs of 50 years ago."

Celebrations of the big event have already begun in the town where he has lived for more than 80 years. Fondazione Riccardo Cassin, run from his home on the outskirts of the town by Marta and other members of his family, is marking his centenary with a series of events intended to continue throughout 2009. Restaurants in the town have launched "Riccardo Cassin" themed menus; and a book of tributes and recollections by fellow climbing heroes such as Messner and Sir Edmund Hillary, 100 Faces of a Great Alpinist, is published today.

Born in 1909 in Friuli, on the other side of the peninsula, Cassin was the first in his family to climb. "My secret was certainly not genetic," he told Federica Valabrega for climbing.com. "My papa died working in a mine in Canada when he was 24, and he never climbed." And Cassin's first sport was boxing. "I boxed for three years before I started climbing. I was in the habit of training in the gym and that built my strength up."

In 1926, aged 17, he moved to Lecco, a town with the Alps on its doorstep, and while toiling as a blacksmith he discovered his life's passion. He and a group of friends who became known as the ragni di Lecco (the Lecco spiders) started tramping up into the peaks at the weekends, first trying the well-trodden local routes then venturing into the Dolomites.

"We had no money but a very strong passion for climbing," Cassin remembers, "so we pitched in 5 cents each and bought a 50-metre rope and some carabiners. Unfortunately, eight of us had to tie into the rope, so we took turns: two at a time would go up, and then they'd throw the rope down and up went the next two."

Climbing was crammed into the little spare time he and his fellow-spiders could steal – and even getting to the start of the climbs could be a feat. "I had to work from Monday to Friday at the steel factory, so I could only climb at the weekend," he said. "I had no choice but to reach the top before dark, because I had to get back to work the next day. And there weren't aeroplanes at the time, just trains, bicycles and lots of walking. To get to Mont Blanc to climb the Grande Jorasses" – a climb still regarded as one of his greatest achievements – "I had to take the train to Pre-Saint-Didier, bike until Courmayeur, and then walk to the Col du Gigante, do half of the Mer de Glace uphill as far as the Rifugio Leschaux, and then get to the tavola (plateau) of the Grandes Jorasses and start the climb. So I was already warmed up."

On the north face of the Grandes Jorasses, part of the Mont Blanc massif, in August 1938, Cassin and two companions conquered what was, according to an Alpine historian, "universally acknowledged as the finest alpine challenge".

"They knew nothing of the Chamonix district," writes Claire Engel in Mountaineering in the Alps, "had never been there before, and in a vague fashion asked the hut keeper where the Grandes Jorasses were. Even more vaguely, the man made a sweeping gesture and said, 'somewhere there.' He had not recognised the Italians and thought the question was a joke. He was greatly surprised when, the next evening, he saw a bivouac light fairly high up the Walker spur."

These were the glory years when Cassin and his friends opened up many of the most famous slopes in Europe. He made more than 2,500 ascents, of which more than 100 were first ascents. With the simplest equipment, crude ropes and hand-made steel pitons, with no helicopters on hand in case of trouble, he wrote the future of his sport on the sides of these mountains. "I always climbed with severity," he told Ms Valabrega. "That is how the mountain became my friend, and never hurt my climbing partners or me. I always brought home everyone who came along, and never lost a friend on a rope."

After the fall of Mussolini, Cassin fought as a partisan. His best friend and fellow climber, Vittorio Ratti, was shot dead at his side as they fought the Germans in the streets of Lecco.

After the war, it was back to the slopes. Cassin had reinvented himself as a designer and manufacturer of mountaineering equipment, and now took on some of the toughest mountains in the world.

The one incident that brings out a little bitterness in Cassin was his exclusion from the Italian team that took on K2, the world's second highest mountain, in 1952. But nine years later, Cassin opened a new route to the top of Mt McKinley in Alaska, America's highest mountain, and received a telegram of congratulations from President Kennedy.

Fifty years after he created the Cassin Route up Piz Padile – the route that so impressed Jocelyn Chavy – he retraced his steps, at the age of 78, and as the press wasn't there to see him do it, later that week he did it again. "I'm stubborn," Cassin admits. "What I start I have to finish. I never came down from a mountain without reaching the top."

Riccardo Cassin: Greatest climbs

*Piz Badile

The north-east face of the 3,308m Piz Badile in Switzerland had never been tried when Cassin succeeded on 14-16 July 1937. He repeated the feat in 1988, aged 78, and again later the same week.

*Grandes Jorasses

On 4-6 August 1938, Cassin climbed the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses on Mont Blanc. In extreme cold, it took 82 hours.

*Mt McKinley

In 1961 he reached 6,178m Mt McKinley in the US by a tough southern route, now known as the Cassin Ridge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments