Refugee crisis: We know about the problem – but how do we address it?

In part four of our series, Memphis Barker explains the sort of measures that could be taken to ensure that a more workable system emerges from the chaos

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The two most important things to remember about the refugee crisis facing Europe are as follows. First, it is not going to end of its own accord: 350,000 people have been registered on the continent’s borders so far this year, more than in the whole of 2014. War, and poverty, will send more over for years to come. Second, Europe has the capacity to take the sting out its tail. What Lebanon faces, with 25 per cent of its population now Syrian refugees, is an emergency.

The entirety of the refugee population within the EU stands at 0.11 per cent: the panic that has erupted in recent weeks stems from years of mismanagement, and political inertia, not the scale of the task itself. While Germany and Sweden have faced reality, most EU nations have done their best to ignore it, and taken in far fewer asylum-seekers than they have the resources to manage, placidly letting thousands waste away in reception centres to the South as they await trial. It is a crisis, but not an insurmountable one, and the urgency at last gripping EU politicians can now be put to use, in order to make migrant and asylum-seeker reception as befitting of Europe’s ideals as possible.

Safe passage to the EU

Many of those refugees who die in transit, either by getting drawn into Libya’s civil war or drowning in the Mediterranean, should not have needed to take such risks in the first place. Nobody has to stand on European soil to qualify for protection under European law.

The trouble is that there is nowhere to claim asylum in Homs, or North Africa, or any of the war-torn states that are driving this tide of migration. So asylum-seekers with a perfect claim to EU refugee status can only take their chances with people smugglers on the long road to Europe, and then at an asylum tribunal once there.

One of the simpler fixes is to lift carrier sanctions on airlines throughout the EU. As things stand, a Syrian who makes it to an airport, and buys a ticket, will not be allowed to board the aircraft. There is no chance that they will have been able to access a European embassy to secure a visa, as none remain open in their country. If British Airways were to then let the Syrian on board minus such documentation, the company faces a fine from the UK Government. Any carrier found to have transported an economic migrant into the EU without the relevant papers can be sanctioned, and as airlines have no way of knowing whether an asylum-seeker’s claim will be successful, they err on the side of caution and lump all those without documents together as “economic migrants”.This should be reversed. It is a tool for the EU to pass the buck for border control to private companies whose primary concern lies with their bottom line. Asylum-seekers who can buy a ticket, fleeing from countries deemed “unsafe”, should be allowed to travel in comfort – by aeroplane, or ferry – into Europe. At a stroke, this would halve business for people smugglers (who charge vastly more for their services than a plane or ferry ticket, at a base rate of around £2,000).

End the Dublin Agreement and establish a common European asylum system

The problems with David Cameron’s pledge to take in 20,000 refugees over five years go beyond the relative paltriness of the offer. By acting unilaterally, as the Prime Minister proposes, the UK harms progress towards a common EU sharing, or quota, system for asylum-seekers – by far the best solution within reach.

There is currently no way for the European Commission to force member states to sign up to Jean-Claude Juncker’s proposal made on Wednesday, of splitting 160,000 asylum-seekers across Europe, according to the GDP, size and unemployment rate of the recipient nation. By choosing to exercise its opt-out, Great Britain provides cover for other states, such as Hungary and Poland, to remain on the sidelines. The more isolated they are, the less chance they have of holding out.

Currently, six member states receive 80 per cent of the asylum-seekers. Even if every one of them was led by a political colossus in the mould of Angela Merkel, this would not be sustainable. A quota is both fair and necessary, given the collapse of the current system.

The Dublin Agreement ostensibly forces arrivals to seek asylum in the state they first make land. Many now simply clench their fists to avoid being fingerprinted, and move on illegally through Europe (177,000 people arrived in Italy last year, less than half stayed to claim asylum). The agreement is clapped out.

How can recalcitrant member states be persuaded to accept a quota? It may be that diplomatic strong-arming from Spain, France and Germany wins out. If more is needed, cuts to EU funding for failure to comply, as suggested by Belgium, should be considered. More controversially still, a market might be established in which member states can trade quota places, paying a fee for taking in fewer. Any tweak that secures a fully unified European response – except cutting the quota total – will be worth it. Solidarity trumps.

Jobs outside Europe

More than 80,000 Syrians now live in Jordan’s Za-atari refugee camp unable to work. Jordan’s rulers fear the influx of Syrian labour. So, as development economist Paul Collier suggests, the EU should incubate an economy near large refugee camps – there is a disused industrial zone, for example, close to Za-atari – to help Syrian businesses set up and sell, with open access to European markets.

These diasporic economies would not disrupt the workforce of host countries much. As Collier proposes, the governments of Jordan and Turkey – which also denies its 1.4 million Syrian refugees labour rights – could be further assuaged with a subsidy for each job created. Those employed would regain some dignity, and may be encouraged to remain where they are, in preparation for re-entering Syria in the event the civil war can be brought to an end, and Isis contained.

Jobs in Europe

Unemployment rates in many European states remain stubbornly high, but that does not mean there are not opportunities for economic migrants, too, in low-skilled agricultural work, or specialised areas. A scheme like the US Green Card Lottery could be set up, offering a formal route to the employment of tens of thousands. With safe routes to claim asylum, alongside these official paths to work, the number risking death in the Mediterranean would drop – and Europe could, morally, get tough on those still attempting to cross by boat, turning them back in the sea, or immediately taxiing arrivals back across.

Create an ‘unsafe countries’ list

The European Commission announced this week that it would create a list of “safe countries”, to make it easier to deport failed asylum-seekers who face no obvious threat in their home country, such as those from the Western Balkans, who make up a startling 40 per cent of asylum claims in Germany this year. Something is missing, though. A list of “unsafe” countries should also be created, with the opposite effect: speeding up assistance for, say, Iraqis and Eritreans.

Improve deportation rates

Just 39 per cent of failed asylum-seekers are sent back to their countries of origin. Chartering flights is expensive, and many member states prefer to turn a blind eye. To do so trades a short-term difficulty for a more serious longer-term one. Economic migrants are encouraged to try their luck, knowing they may be able to stay in any case. Resentment grows within European populations, who need to be reassured that the asylum system is enforceable and sustainable, and that jobs are not under threat from failed asylum-seekers willing to work for next-to-nothing. So charter more flights – and throw the right-wing media some red meat in the process.

Frontex, the EU’s border agency, can do more to help here, by working across all member states as the point of contact with countries of origin. This would remove the challenge of each member state individually fostering “readmittance” relations with countries as varied as Nigeria, Sudan and Pakistan.

Tie aid to sub-Saharan Africa to readmission of its citizens

The low deportation rate can be in part explained by mistrust between the EU and African countries of origin, to which failed asylum-seekers would be returned. The £1.8bn fund proposed in compensatory development funding to African nations will repair relations, to a small degree. It is quite reasonable for aid policies to be used as leverage on top of this, on a “more for more” basis.

The EU already has a development relationship with sub-Saharan African nations, known as the Cotonou Agreement, that stipulates any citizen from, say, Zambia, can be returned without any bureaucratic hold-ups. In reality, more pressure must be applied to see it upheld.

Returning more people to sub-Saharan Africa would furthermore relieve pressure on North African nations, often asked to take back migrants who have “transited” through them. This may in turn help secure much-needed readmission agreements with those nations.

Better information in countries of origin, focused on the travails that can await in Europe, has been called for by migrants who do not feel the rewards of the journey match its arduousness. Draconian though it may sound, requesting that returnees assist in any “ward away” campaign, as a condition of their reintegration assistance, would make sense. So would increasing the amount of assistance they receive.

Build more and better ‘hotspots’

The “hotspot” approach, still embryonic at this stage, piles together all the relevant EU agencies and NGOs in one place, typically a Hungarian, Greek or Italian reception centre. The aim is to speed up asylum claims – and work together on criminal matters – where national services are flimsy or overcome entirely. Directing EU efforts to Europe’s fringes, and combining them there, is smart. Smarter still would be to separate the funding for infrastructure from the general pot available for migration matters in these countries, and increase it.

The reception and detention centres in Hungary, Greece and Italy are over-crowded and inhumane: so build more, and, through the vigilance of the EU agencies, make sure they operate to common standards.

Get trials right the first time

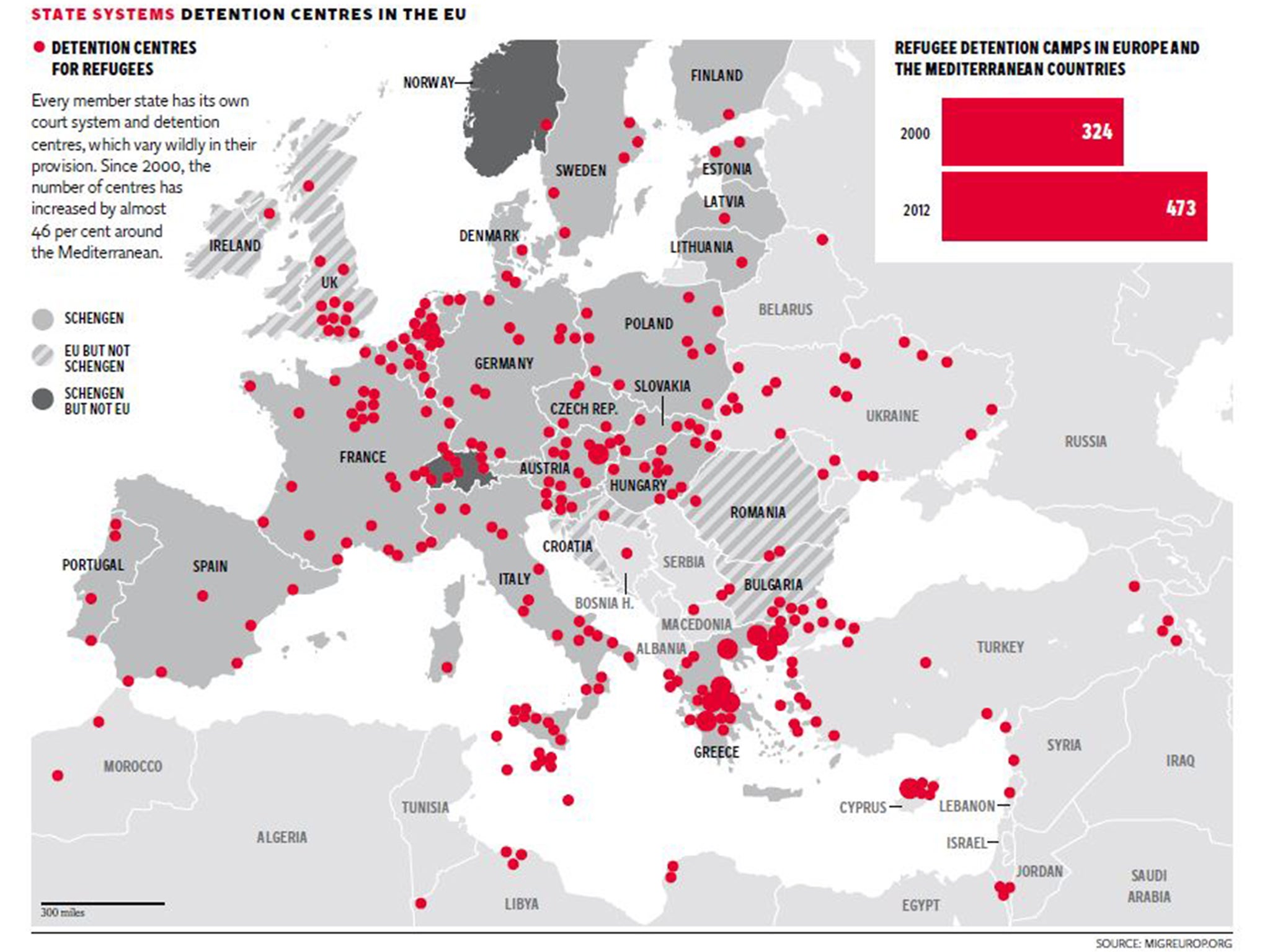

Every member state has its own unique court system, and they vary wildly in their provision for asylum-seekers. In Italy, unspecialised civil courts handle the cases. Germany, on the other hand, has courts tailored specifically to asylum-seekers from Afghanistan, for example.

There is no feasible way to harmonise asylum tribunals across Europe. Even the sensible step of referring appeals to a European-level court will take more than five years to implement, if it comes to pass at all. Information, however, could be far better shared. The European Commission should issue a regularly updated briefing on the countries of origin, advising lawyers and judges on the latest cracks in the world outside its borders.Resources, meanwhile, should be frontloaded, so that every possible effort is made to ensure an asylum-seeker gets a fair and accurate trial on the first outing. In Italy, forced by the Dublin Agreement to take on a disproportionate number of cases, some 60 per cent of denied applications are overturned on appeal. This clogs up the court system, and mires people with a valid claim to protection in years of waiting around, often in detention, unable to work and add to the economy, before the correct decision is reached. More and better lawyers, and more linguistic and cultural intermediaries, must be directed to the first trial.

Be realistic on smuggling

Wherever there are people, and boats, there will be smugglers. Attempts should still be made to stop them, but in full knowledge that they are a symptom, not a cause, of the refugee crisis, and will never be stopped. When a politician mentions smuggling, it tends to be because they lack the stomach for serious assistance to the world’s migrating people.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments