Refugee crisis: As Hungary closes its borders, what are the alternatives for asylum seekers?

Hungary is attempting to close its border with Serbia to migrants and refugees

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Hungary tries to close its border to stop the arrival of thousands of asylum seekers, Europe's strategy for tackling the refugee crisis is falling apart.

Germany has introduced temporary border controls, while Austria, Slovakia and the Netherlands have threatened the same, potentially stopping the flow of people trying to reach northern Europe through the Balkans.

Meanwhile, a government minister in Serbia, where thousands of refugees are stranded after being prevented from crossing into Hungary, has said it will not become a "concentration camp" for the rest of Europe.

A state of emergency was declared this morning in two of Hungary's southern counties bordering Serbia, giving authorities special powers that could see the army deployed.

Under laws that came into effect overnight on Monday, railway crossings from Serbia have been stopped as mounted police await anyone trying to scale the 13ft fence running for 110 miles along the border.

Anyone found trying to cross illegally will face criminal charges, with 30 judges on standby to try expected offenders, while others will be detained in processing centres or turned back to Serbia if their applications are refused.

But Aleksandar Vulin, Serbia's minister for labour and social policy, claimed that his country was not a "concentration camp" where people could be sent against their will.

"They have not done anything wrong by any criminal law," he added, according to a translation reported in The Telegraph.

"You cannot send them to Serbia without their permission.

"These people don't want stay in Serbia. They want to travel to Europe or wherever they want. We are not a concentration camp and we do not expect anyone to consider us as a concentration camp."

He harshly criticised Hungary's response to the crisis, saying it was "hard to believe" the sights of barbed wire fences and "babies and children being treated without any kind of human dignity".

Hungarian authorities said more than 9,300 people crossed its border on Monday before it was closed – a new record – and similar numbers were expect to build up on the other side over the coming days as their attempts to reach Western Europe continue.

If Hungary successfully closes its border, where can they go?

Migrants and refugees who are already in Serbia could either divert westwards, into Croatia, and then on into Slovenia and Austria, or east through Romania and back into Hungary over its less heavily guarded border.

Both countries are part of the European Union but are not in the Schengen zone, meaning people must travel further to apply for the right to border-free movement.

Humanitarian groups have warned the closure will force desperate families to take ever longer and more treacherous journeys to reach western Europe.

Can the refugees settle in Serbia instead?

Hungary has declared Serbia a “safe third country” for asylum seekers, allowing them to send refused refugee applicants back, but the UN’s refugee agency disputes the classification.

Rights groups say it meets none of the criteria and is still finding homes for thousands of its own refugees from the collapse of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the last time Europe confronted displacement of people on such a scale.

Why are so many people trying to cross from Serbia to Hungary?

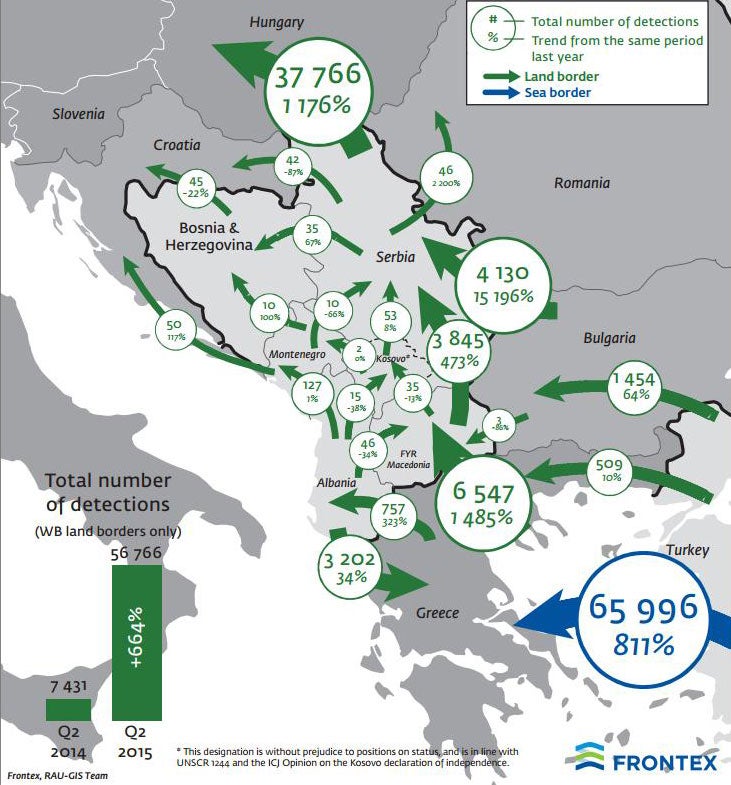

The border is part of the Western Balkans migration route into Europe, which has become one of the dominant entry points for people fleeing conflict in Syria and other parts of the Middle East this year.

People enter through the Bulgarian-Turkish or Greek-Turkish land or sea borders and then journey through several more countries, including Macedonia, to reach Hungary.

According to Frontex, the EU’s border agency, 37,766 “illegal crossings” were made from Serbia to Hungary between April and June this year, up 1,176 per cent from the same period in 2014.

Other borders in the area, including in neighbouring Croatia, saw fewer than 7,000 crossings each.

Analysis shows a direct link between refugees crossing into Hungary and those arriving on Greek islands from Turkey over the Aegean Sea.

“The high pressure on the Aegean Islands is later echoed on the Western Balkan route with a certain time lag, which is basically the time migrants need to organise their onwards movements,” a spokesperson for Frontex said.

Although European law under the Dublin Regulation stipulates that asylum seekers should lodge their claims in their country of arrival in the EU, the influx of people into Italy and Greece has overwhelmed the infrastructure and meant that thousands of people continue their journey before registering with authorities.

Are refugees still arriving in other parts of Europe?

Yes, in huge numbers. Frontex figures for January to June this year showed that although the Western Balkan route was the busiest, more than double that number of people were arriving over the Mediterranean.

From January to June this year, more than 102,000 refugees and migrants, mainly from Afghanistan and Syria, arrived over the Western Balkan route.

But 91,300 more had come over the Central Mediterranean during that period, on voyages between Libya and Italy that have killed more than 3,000 so far this year.

A further 132,000 people arrived over the Eastern Mediterranean route from Turkey to Greece, many of whom possibly continued their journey to Hungary, and 7,000 more migrants and refugees used the Western Mediterranean passage from North Africa to Spain.

More than 500,000 people had crossed into the EU in 2015 by the end of August and the numbers are not falling.

Are journeys getting safer?

No. More than 300,000 refugees and migrants have used the dangerous sea route across the Mediterranean so far this year, with almost 200,000 of them landing in Greece and a further 110,000 in Italy, the UNHCR said.

“At the same time, some 2,500 refugees and migrants are estimated to have died or gone missing this year, trying to reach Europe,” spokeswoman Melissa Fleming said.

That toll did not include a disaster on 26 August off the coast of Libya, where 51 people were found suffocated in a hold.

“According to survivors, smugglers were charging people money for allowing them to come out of the hold in order to breathe,” Ms Fleming said.

She quoted one survivor, 25-year-old Abdel, from Sudan, as saying: “We didn't want to go down there but they beat us with sticks to force us. We had no air so we were trying to get back up through the hatch and to breathe through the cracks in the ceiling.

“But the other passengers were scared the boat would capsize so they pushed us back down and beat us too. Some were stamping on our hands.”

Drowning also continues to be a risk, as illustrated by the tragic death of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi when his family’s dinghy capsized as they tried to reach Greece.

What is being done to stop the deaths?

Some countries are emphasising the need for refugees to be given safe passage and homes inside Europe, while others, including the UK, maintain that the conflicts driving people from their homelands must be addressed.

The UNHCR welcomed the European Commission’s proposals to relocate 160,000 people from the main entry points of Greece, Italy and Hungary but said legal channels for migration must be expanded.

“With more legal alternatives to reach safety in Europe, fewer people in need of international protection will be forced to resort to smugglers and undertake dangerous irregular journeys,” a spokesperson said.

“While calling for strong measures to be taken against people traffickers and smugglers, UNHCR insisted that the management of borders needs to be consistent with national, EU and international law, including guaranteeing the right to seek asylum.”

This newspaper has started a campaign for the UK to welcome a fair share of refugees.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments