How a Sussex manor house became a country club for Russian spies

Gifted to the former Soviet Union after the Second World War, this grand pile has long enjoyed hosting Russian diplomats for tennis days and musical soirees. But that all came to an end this week when it was stripped of its special status, much to the relief of the locals, who have been warning about suspicious goings on for years, says Mark Hollingsworth

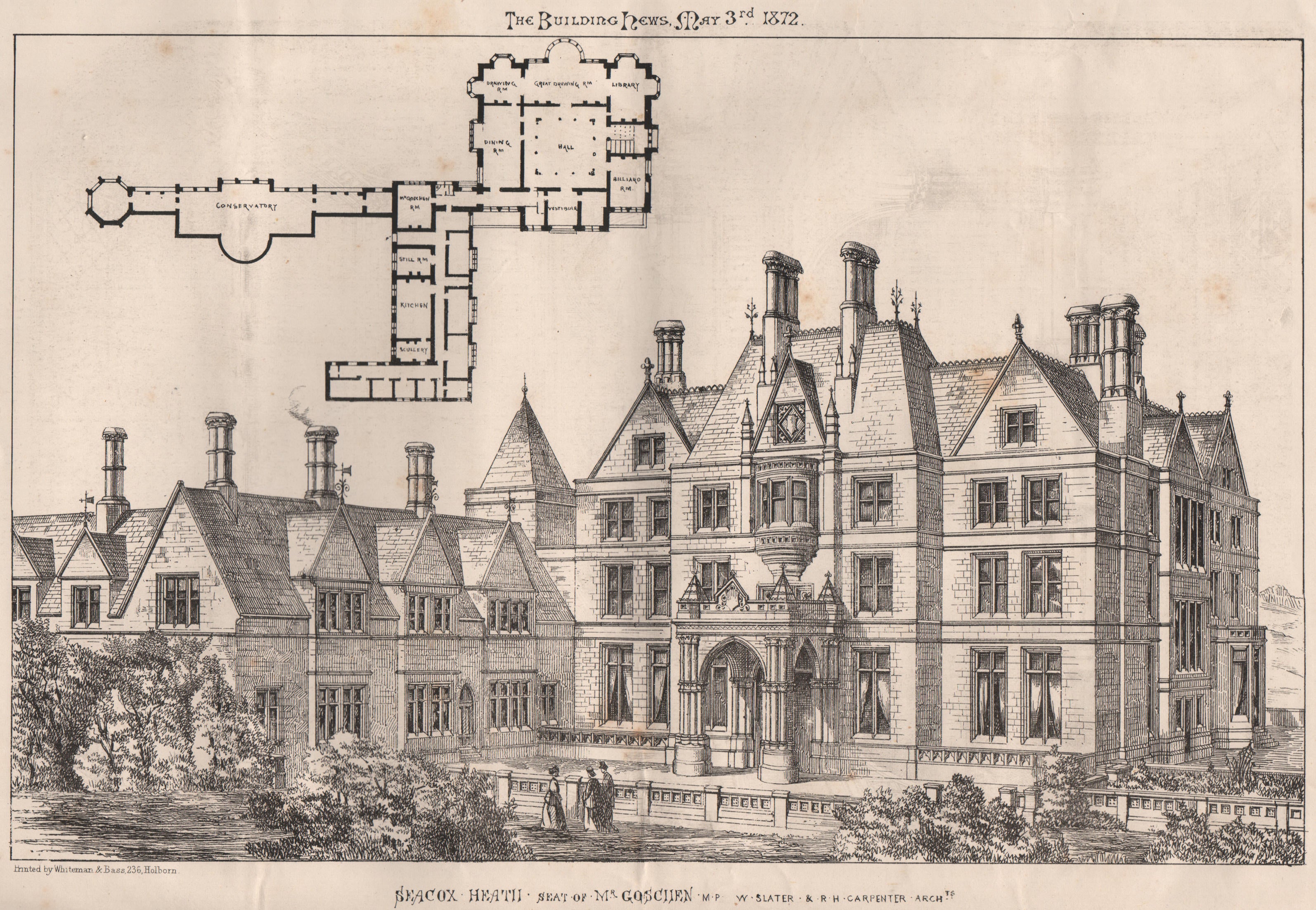

At first glance, Seacox Heath, an imposing 19th-century Gothic castle with its turrets, chiselled balconies, tennis courts and terraced lawns, doesn’t seem the likeliest secret base for Russian espionage operations.

Sitting in the sleepy countryside near Hawkhurst, Sussex, the grade-II listed 50-room mansion looks more like a country house for an eccentric tycoon. But in fact, since 1947 it has been used by Russian diplomats and their associates as a weekend retreat.

Since the Second World War, KGB and now FSB officers based at Seacox Heath have enjoyed diplomatic immunity from police prosecution. But last week, that special status was removed by the Home Office, which accused the Kremlin of using the castle and its 30 acres of grounds to plot espionage operations against Britain. Then, a military intelligence officer, Colonel Maxim Elovik, was expelled for undeclared spying activities.

The decision has major ramifications, and not just for Russian spies. It provides a legal opportunity for the government to take ownership of Seacox Heath, worth an estimated £20m, sell it and distribute the funds to the victims of Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine.

After all, since 1999, Ukraine has a registered caution (beneficial interest) against the mansion as part of an unresolved dispute about the distribution of property after the Soviet Union was disbanded and Ukraine became an independent state.

The removal of its diplomatic status also means the castle becomes a Russian state asset and so vulnerable to being seized by an individual or company with a successful court judgement against the Kremlin.

The East Sussex dacha has a colourful past. In the mid-1700s, it was the refuge of Arthur Gray, the leader of the Hawkhurst gang, and from which the notorious smugglers led raids across the coast of Dorset. The existing structure was built in 1871 by the 1st Viscount Goschen, a former chancellor of the exchequer. His son gave it to the Soviet Union in 1947 as a gift, after Russian sailors saved his son during the Second World War.

At weekends during the Cold War, Russian spies relished the surroundings of Seacox Heath with its Gothic arches, elaborate corridors dominated by portraits of Stalin and a spectacular three-storied galleried central hall. It was, of course, in stark contrast to the bleak soulless Soviet architecture back in Moscow. During the summer the gardens, tennis courts, football pitch and two detached cottages were full of the wives and children of spies and diplomats.

KGB and other security officers frequented the local pubs and would go rambling in Bedgebury forest. One neighbour was Ruari Chisholm, former MI6 station chief in Moscow. One day, his friend John Miller, a foreign correspondent based in the Soviet Union, noticed some late-night activity at the castle. “From the end of his garden you could sometimes see the KGB burning their shredded secret files on a bonfire,” recalled Miller. “We once sneaked into the back garden and kicked over the ashes for a disappointing reward: the only thing readable was a list of items on a BBC news broadcast.”

As the Cold War intensified in the early 1980s, the castle was restored to its former glory. The leaking roof and sealed-off wings were repaired, and the Soviet ambassador hosted days spent playing tennis, and musical and cultural soirees. Some local haunts became KGB favourites too. One preferred pub was the Hare and Hounds, a 17th-century inn in nearby Flimwell where they would drop by late at night for a beer (never vodka).

The landlord, Peter Benn, recalled how “Russian-speaking special branch men” rarely engaged with the punters but did ask questions. One occasional patron was the active KGB officer Sergei Ivanov who in 1983 was expelled from the UK and banned from returning.

An embarrassing security risk was averted, despite the presence of Sir Denis Thatcher, who regularly drank his multiple gin and tonics at the Hare and Hounds as he lived nearby at The Mount, in Lamberhurst.

Fortunately, the prime minister’s husband was not in the bar at the same time as the Russian spies, according to Mr Benn. If Sir Denis and the KGB operatives had got drunk together, who knows what secrets could have been divulged.

Local residents have never been happy with the presence of the Russian spies. In 1999, the Seacox Heath estate was at the centre of a row with a local sheep farmer who accused the Russian embassy of letting loose a pack of Alsatians that killed 50 ewes. An embassy spokesperson was dismissive at the time, saying: “The estate is our property and everything there is covered by diplomatic immunity according to the international convention and so yes, the dogs have immunity but the dogs are not diplomats.”

No doubt the Russians based at Putin’s British country estate are currently wondering how long the good life in the English countryside can now last for the rest of them

After the Ukraine war began in 2022, the locals staged a protest by placing flags and spraying pro-Ukrainian graffiti at the entrance to the house. Last year, villagers complained of drones being flown from the estate over their homes, moving down residential streets before being returned to base.

Some believed that these drones were dispatched by Russian officials in retaliation against the locals who had staged the anti-Putin and anti-war protests. Sussex police confirmed it had investigated the sightings and spoken to Russian officials inside the mansion.

Now that Seacox Heath has lost its diplomatic status, the estate is uniquely vulnerable to being confiscated and sequestrated. The estate remains owned by the Russian Federation. But it could also be seized by the former shareholders of Yukos Oil, who have successfully sued Russia for the illegal expropriation of their investments and have been awarded £40bn in damages by the courts.

The Kremlin has refused to pay and argues its assets are protected by sovereign immunity. But now that Seacox Heath’s diplomatic status has been stripped away, the Yukos Oil shareholders may file an application to the High Court to take ownership.

Ukraine may also stake a claim on Seacox Heath. In 1999 Ukraine, as a founding member of the Soviet Union, challenged Russia’s ownership of the estate. The issue of the equal distribution of the property remains unresolved.

Documents filed at the Land Registry state the Ukraine government has a “beneficial interest” in Seacox Heath, as it was owned by the Soviet Union. A caution (also known as a charge) has been filed and so Ukraine is likely to have the first option on the proceeds of any sale.

No doubt the Russians based at Putin’s British country estate are currently wondering how long the good life in the English countryside can last for the rest of them. If they move to a new property in London they will be protected by diplomatic immunity. But whether any new residence could be a match for the elegance and grandeur of a 19th-century Gothic castle on the Kent-Sussex border remains to be seen.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments