Patrick Edlinger: The highs and lows of France’s pioneering rock god

The rock-climber, who gave the sport mass appeal but was beset by inner demons, has died at 52

Patrick Edlinger was one of the most extraordinary sportsmen of all time. He never won an Olympic medal. He never became a millionaire.

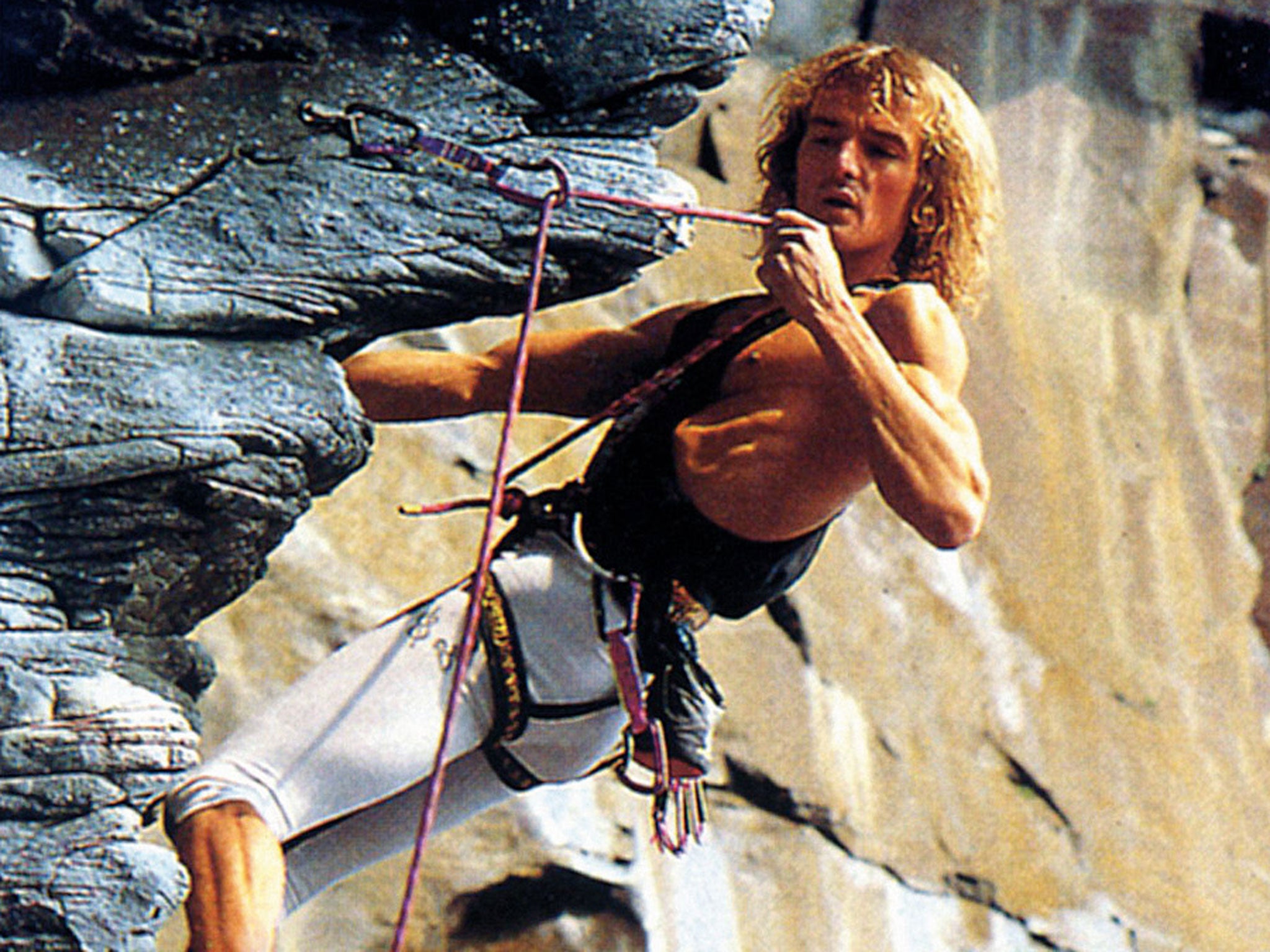

For a few years in the 1980s, he was celebrated far beyond his native France for turning rock-climbing into a compelling but terrifying version of gymnastics or yoga, performed far above the ground without safety equipment.

Mr Edlinger, whose death aged 52 was revealed this week, became a mythical figure partly because he defied the glitzy spirit of the 1980s. He had the looks of a film-star, the body of a ballet-dancer, and the long, blond hair of contemporary tennis and football idols. But he clung to an ascetic, bohemian existence, living in a white camper van and claiming that he survived on water and sandwiches.

After a serious fall which almost killed him in 1995, Mr Edlinger retired from the extreme forms of "free climbing" and ran a guesthouse in the French Alps. His death followed a long battle against depression and alcoholism which he described recently as the "greatest challenge of my life". Mr Edlinger's exploits have been re-discovered by the availability on the internet of two breathtaking films made about him by Jean-Paul Janssen in 1982 and 1986: La vie aux bouts des doigts (Life at your Fingertips) and Vertical Opera.

Wearing a shirt and shorts, Mr Edlinger is seen, without a rope, and sometimes without shoes, gracefully swarming up 1,500ft limestone cliffs in the south of France or sea-battered Mediterranean cliffs near Marseille. He frequently hangs from the cliff by two or three fingers, like a gibbon or chimpanzee. He holds on by one arm and effortlessly throws his body over a rock-overhang, as if mounting a horse. He wedges both his feet into a crack in the rock and turns upside down like a bat to "rest" and "regain concentration".

"When I climb I feel an interior peace," he once said. "You can compare it to a form of yoga."

Mr Edlinger also became the undisputed world champion of "sport climbing". Exponents use metal bolts permanently fixed in rock faces or walls to compete to find the most elegant and rapid routes to the finish. Mr Edlinger's pioneering work helped to project the sport to global popularity.

He shot to fame when he appeared at the first US sport climbing competition in Snowbird in Utah in 1988. A dozen climbers failed to conquer the 100ft route up the wall of the Cliff Lodge hotel. As Mr Edlinger danced gracefully past the roof overhang which had defeated the others, a shaft of sunlight struck his long blond hair.

"It was literally a beam, like a spotlight illuminating him and nothing else," John Harlin, a former editor of American Alpine Journal, told The New York Times. "If this were a Hollywood movie script, it would (have been) way too corny."

Catherine Destivelle, a friend and follower who became a leading climber, said this week: "No one else could match Patrick's method of climbing… He had a magnificent technique. It was like watching a lizard on a rock."

Daniel Gorgeon, another friend and fellow climber said: "When he climbed, it was like watching a ballet… It looked like a professional dancer on the rocks. The moves weren't rough. They were always purposeful and beautiful."

Patrick Edlinger was born in 1960 near Dax in south-western France. He started climbing at the age of eight. He gave up studying in his mid-teens and headed to the limestone cliffs of the Luberon in Provence. He trained by running and performing up to 1,000 press-ups a day (sometimes using only one finger).

After the terrible fall in 1995, Mr Edlinger retired to run his guesthouse at La Palud-sur-Verdon in the southern French Alps. He continued to climb a little each day. He married and had a daughter 10 years ago. But he confided to his friend and biographer Jean-Michel Asselin that he had suffered from depression and alcoholism after his fall. Mr Asselin's joint book with Mr Edlinger will be published next month. He said this week that Mr Edlinger had told him that his struggle against alcohol was "the most difficult challenge of my life. It's like attempting an impossible solo climb. But I will get there in the end."

Mr Edlinger, who had separated from his wife, was found dead at his home on 16 November. His death was made public this week. The cause of death has not yet been established.

"It's thanks to [Patrick] that there are so many thousands [of sport and free] climbers today," Mr Asselin said. "He had a style and elegance which ran counter to the spirit of the 1980s, when only making money counted."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies